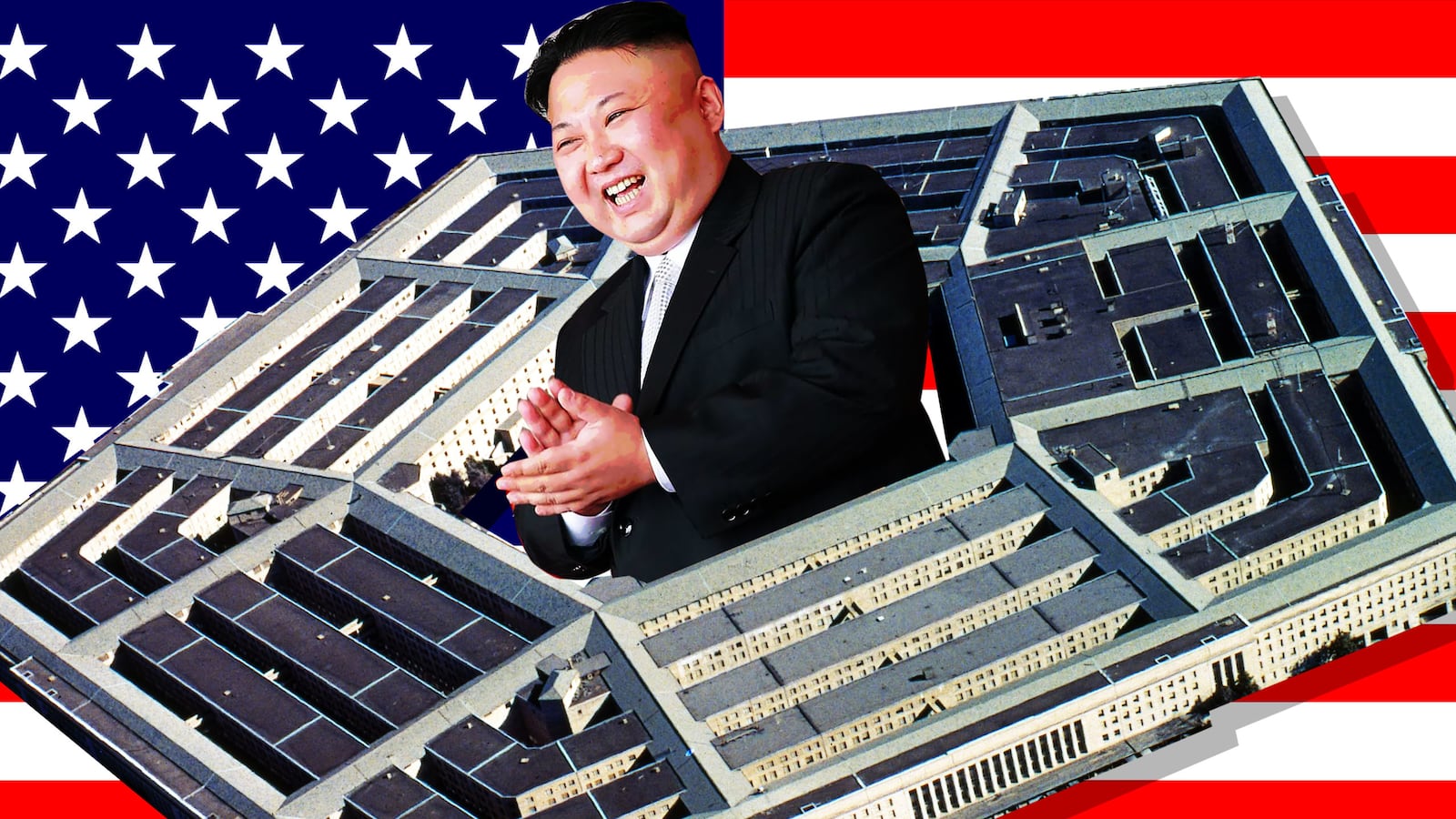

The Trump administration launched its week with tough talk aimed at North Korea—barbs all the more remarkable because they caught some senior officials at the Pentagon off guard.

The salvos started with U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley announcing what sounded like a red line that would lead to a preemptive U.S. strike on the regime of Kim Jong Un.

“If you see him attack a military base, if you see some sort of intercontinental ballistic missile, obviously, we’re going to do that,” Haley told NBC News. Those remarks caught senior U.S. defense officials unawares. The Trump administration had previously kept details deliberately vague, saying only that all options are on the table if Pyongyang steps out of line.

President Donald Trump followed Haley’s salvo by telling visiting U.N. ambassadors that the “status quo in North Korea is also unacceptable,” calling on them to step up sanctions aimed at North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile programs—a mild statement compared to that of his U.N. ambassador.

At the Pentagon, there was another ominous sign when officials announced an extraordinary classified briefing for all U.S. senators on Wednesday, to be held at the White House, with the secretaries of defense and state, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and the director of national intelligence briefing the lawmakers.

“The minute North Korea gets a missile that could reach the United States, and put a weapon on that missile, a nuclear weapon… this country is at grave risk,” Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly told CNN on Sunday, adding that he thought Trump would have to deal with this “before he starts his second term.”

Longtime Asia watchers worry the secretive North Korean regime will give all the statements the same weight—a challenge issued by a Trump administration that must be answered. Pyongyang has already detained a third American, Professor Kim Sang-duk, at the country’s airport, and threatened to sink the U.S. naval battle group that’s now steaming in its general direction.

All of this activity comes in advance of another possible nuclear weapons test this week. Tuesday is the anniversary of the founding of North Korea’s armed forces—which would have provided a reason anyway for some sort of demonstration of military might. The watchdog site 38 North reported increased activity at the Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site, pointing to a likely underground nuclear test in the works.

In the midst of this, China’s President Xi Jinping spoke to Trump by phone Sunday, perhaps worried that the strategic game pieces are aligning at odds with each other in ways that might take a life of their own.

From Capitol Hill to the Pentagon, lawmakers and other officials expressed frustration that they’re not sure what the White House’s North Korea strategy is.

Multiple defense officials told The Daily Beast that they weren’t expecting Haley to signal to the world what might trigger an armed American response. There’s a daily phone call between the different U.S. agencies to align or share messages, but this never came up, one of them said. All of the officials spoke anonymously to discuss the confusing cacophony of administration comments.

The lack of coordination is similar to the comedy of messaging errors over the location of the U.S. Navy’s Carl Vinson battle group, which is now on its way to the Sea of Japan, and the lack of coordinated information response to the use of the largest bomb ever dropped by the U.S. in Afghanistan. The president and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis had described the battle group as headed to the north Pacific to bolster any needed response to North Korea, not aware that the ships were making a side stop for an exercise with the Australian navy. And the use of the “Mother of all Bombs” against an ISIS cave hideout in Afghanistan caught many in the U.S. administration off guard, two of the defense officials said.

A senior administration official pushed back against the idea that Haley issued a red line by articulating that attacking a military base or launching an intercontinental ballistic missile would draw fire. She did soften that under further questioning, saying that if North Korea did something like launch an ICBM, the president would decide what to do next. The senior official said that means “no red line.”

The senior defense officials saw it differently—as a major strategic message to Pyongyang about how far they might be able to go before triggering retaliation.

“As a general rule, you should not just throw out hypotheticals,” said former Obama National Security Council spokesman Ned Price in an interview Monday. “It sends a signal to our adversaries that this is a red line, but they can do everything up to that.” Price said he could not recall the Obama administration ever defining what might trigger a response.

“I think what we are seeing here is a lack of a coherent policy so that leads to lack of coherent messaging,” he said.

(Price demurred when asked if his President Obama decided not to set a red line for Pyongyang after getting so much grief about not bombing when Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad crossed a red line in Syria. But Price did point out that Obama used the threat of such force to get Assad to give up what was thought to be most of his chemical weapons.)

North Korea has conducted several missile tests that have threatened its immediate neighbors. The latest such test, of a midrange missile, failed last Sunday. But Pyongyang has shown recently that the accuracy and capacity of its arsenal is fast improving.

On March 6, it launched four ballistic missiles that traveled 620 miles and landed on or near the Japanese maritime economic zone in the Sea of Japan, apparently hitting their exact intended point. Various Tokyo officials expressed more concern that they have in the past about the Kim regime’s missile capabilities.

“Those missile tests are provocative,” a U.S. official told The Daily Beast. “But ICBMs, which can hit the U.S., are in a totally different category.”

Specifically, if the North tests a ballistic missile that can reach America’s mainland, the world could see a revival of the Cold War doctrine known as MAD, or Mutual Assured Destruction: a situation in which both sides threaten each other with enough ruin to prevent them—as long as both are sane—from attacking each other.

“It’s not exactly that,” said Anthony Ruggiero of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. The former U.S. official, who worked on sanctions, including against North Korea, said the danger “is less MAD than North Korea gets to dictate the military action. Nuclear brinkmanship changes the dynamic.”

Ruggiero, like Trump, called for more sanctions on North Korea, pushing back against the notion that it is the most sanctioned in the world. He suggested naming and shaming Chinese companies and banks that do business with North Korea to add pressure on the Pyongyang regime. While he said this may limit America’s option to impose international sanctions through the U.N. Security Council, where China has a veto power, it may well be more effective. Unilateral U.S. sanctions, by limiting access to international banking, have in the past proved to be as effective if not more so than international ones, he said. “If countries have a choice between doing business with us or with NK, I think choose us.”

How far is Pyongyang from developing the kind of missiles that can hit the U.S. mainland? On April 16, during an annual military parade, two types of ICBMs were on display, raising fears that it is getting closer to completing the process of obtaining the long-range missiles.

While some observers dismissed the display as possible “cardboard models,” Tal Inbar of the Fisher Institute for Air and Space Strategic Studies, a think tank founded by the Israeli Air Force, noticed some design details that made him believe the models were genuine.

“Every nut and bolt in the missiles we saw on that parade looked like the real deal,” he said, adding, “I don’t believe in mock-ups in the DPRK,” short for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Inbar, a leading missile expert, said that while we only saw the missile casings in the parade displays, and therefore we can’t be sure how advanced the program is, the more worrisome sign was that they showed that North Korea has two separate ICBMs designs. “What we saw was a representation of two completely different types of missiles, and both can reach New York,” he added.

Asked by The Daily Beast last week about threats made by Pyongyang officials, Haley said her message was simple: “The United States is not looking for a fight, so don’t try and give us one.” Haley has used a similar formulation several times since, indicating that additional provocations from the Kim regime would force the U.S. to act.