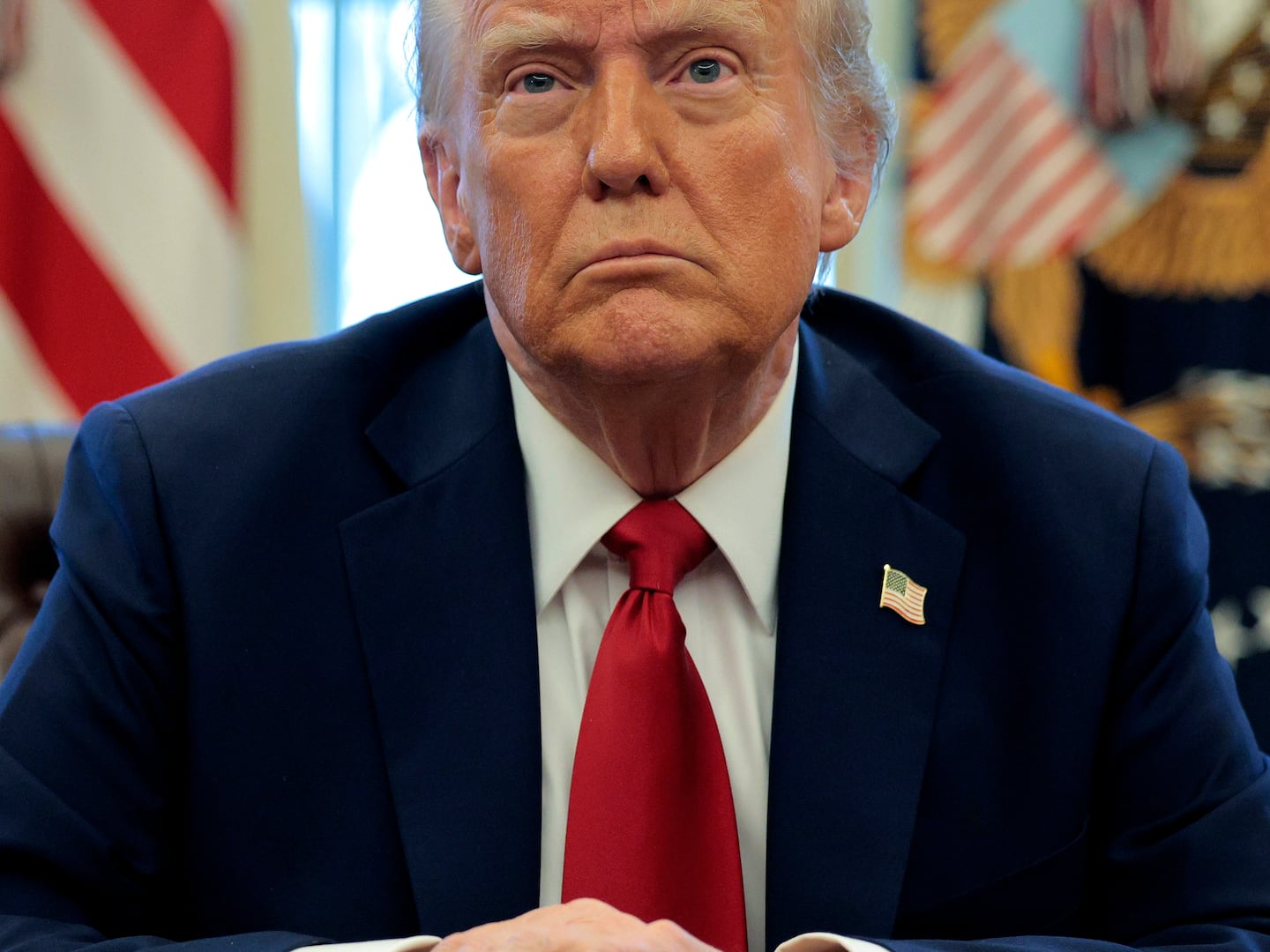

Even as President Donald Trump says Iran is “not living up to the spirit” of its nuclear deal, his friend Rudy Giuliani— formerly a harsh critic of the mullahs — is working to bypass the Justice Department and cut a deal for a Turkish gold trader accused of aiding Tehran’s “economic jihad.”

At a conference before a federal judge Monday, prosecutors slammed affidavits filed by Giuliani and Michael Mukasey, a former attorney general under George W. Bush, who are both working on behalf of a Turkish citizen accused by the U.S. of violating sanctions on Iran. That case, by far the most significant one against an alleged sanctions-buster as the Obama administration raced to reach a deal with Iran, was brought by U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, who Trump fired last month. (Trump has reportedly considered replacing Bharara with Marc Mukasey, who is Michael’s son and also Giuliani’s longtime law partner.)

But fresh off consideration for being the next Secretary of State, Giuliani is now batting for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. After Zarrab’s arrest, the Turkish leader waged a bitter battle of words and charges against Bharara, accusing him of a vendetta and of being in cahoots with Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, an exiled cleric often blamed by Erdoğan’s government. Bharara was even named in a Turkish government investigation into an attempted coup over these supposed ties to the Poconos-dwelling Gulen.

So while the Turkish government has launched what appears to be a retaliatory criminal probe of the former United States Southern District U.S. Attorney, another former SDNY USA and an American attorney general are working to shortcut the Justice Department to cut a diplomatic deal on behalf of Erdoğan’s ally.

At issue are alleged ties between Zarab and senior Turkish government officials, first exposed in a corruption scandal in Turkey. Some Turkish leaders are reportedly worried that if the sanctions case goes to trial in Manhattan, they may be implicated in the sanctions-bypass scheme.

In a deposition unsealed last week, Giuliani said that his role in the Zarrab case is to “determine whether this case can be resolved as part of some agreement between the United States and Turkey that will promote the national security interests of the United States and redound to the benefit of Mr. Zarrab.”

The affidavits about work done by Giuliani and Mukasey “muddied the waters a little bit,” charged assistant U.S. attorney Michael Lockard at the Monday hearing.

“There’s also in the affidavits a suggestion that the conduct in this case is not serious or harmful to the United States,” he said quoting a line from the affidavit about the case concerning “consumer goods.” “That characterization is not an accurate one.”

Instead, Lockard rattled off a list of entities involved in the case sanctioned for involvement with Iran’s nuclear program, work in Iraq and Syria, or with the Iran Revolutionary Guards Corps. “This is a serious national security matter,” he said.

But that wasn’t the only problem with the affidavits, according to prosecutors. They “each contain a suggestion that there has been a leak of information of misinformation,” Lockard said.

On the contrary, Lockard said there were no leaks about Giuliani and Mukasey’s negotiations. Rather, prosecutors never promised them that information would be kept confidential, and brought the matter before the judge to address any potential conflicts.

Federal prosecutors, now working under Acting U.S. Attorney Joon Kim, say Reza Zarrab used a network of companies to help Iran evade sanctions by trading the country gold for oil and gas. He was arrested in Florida last year, while on a trip to Disneyland with his wife and daughter.

Zarrab has been in federal lockup ever since, but Giuliani and Mukasey are trying to get him off the hook through diplomatic, rather than judicial, means.

He and Mukasey have met with top-level leaders in Turkey, including Erdoğan, and in the U.S. to try and cut a diplomatic deal. Giuliani anticipates “further meetings or conversations with senior officials of the governments of the United States and Turkey.”

This turn of events is not entirely unexpected for Zarrab, who has ties to the Erdoğan family, and who is married to a top pop singer in Turkey (who is believed to have filed for divorce). Foreign Policy reported he was "at the heart of the probe" in Turkey into a group of people accused of crimes including fraud, gold smuggling, and bribing high-ranking Turkish government officials. (Those charges were dropped after Erdogan intervened.)

In the U.S. case, Zarrab is charged with using a network of companies to make wire exchanges involving U.S. banks that would omit mentions of Iran. The plan supposedly arose after Iran was barred from the SWIFT international money transfer system, and instead routed the transactions through Turkish banks. The complaint also accuses Zarrab of conducting transactions on behalf of the Iranian Ministry of Oil and other companies. But eventually they got tripped up. In May 2011, an American bank allegedly stopped a nearly €4 million transfer because of potential Office of Foreign Assets Control violations. Such warnings continued.

The prosecutors allege in their complaint that Zarrab received a letter in Farsi, prepared for his signature and addressed to the general manager of the Central Bank of Iran, detailing a plan by Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, and the bank that “wisely neutralizes the sanctions and even turns them into opportunities by using specialized method.”

“It is no secret that the trend is moving towards intensifying and increasing the sanctions, and since the wise leader of the Islamic Revolution of Iran has announced this to be the year of the Economic Jihad, the Zarrab family [...] considers it to be our national and moral duty to declare our willingness to participate in any kind of cooperation in order to implement monetary and foreign exchange anti-sanction policies,” the letter allegedly continued. “Hoping that the efforts and cooperation of the zealous children of Islamic Iran will result in an upward increase in the progress of our dear nation in all international and financial arenas.”

Less than a year ago, Giuliani didn’t mince words when attacking Iran.

"The ayatollah is insane. The people around him are insane," Giuliani said in September, also calling them "suicidal homicidal maniacs," according to the Jerusalem Post.

But in the affidavit, he dismissed Zarrab’s alleged crimes as second-tier, because “none of the transactions in which Mr. Zarrab is alleged to have participated involved weapons or nuclear technology, or any other contraband, but rather involved consumer goods.”

Giuliani and Mukasey’s role didn’t go unnoticed by prosecutors, who pleaded with judge Richard Berman to investigate what they were doing. Zarrab’s attorney Ben Brafman objected that Giuliani and Mukasey would never even appear in court, so their work was out of its purview and fell under attorney-client privilege.

But the judge decided the court has dual interests in the case: To protect the integrity of the judicial process, and to ensure that Zarrab gets a fair trial. And because the objections raised by the assistant U.S. attorneys included cries of potential conflicts of interest on the part of the men’s firms, Berman opted for special precautions. (Both Giuliani and Mukasey’s firms do business with U.S. banks designated as alleged victims in the complaint, and Giuliani’s firm is a registered agent of Turkey.)

Both Giuliani and Mukasey submitted court-ordered depositions ahead of Monday’s hearing, outlining in the most general terms their work on the case. Berman set a schedule of future meetings at the hearing, including two at which court-appointed lawyers will make sure Zarrab, and co-defendant Mehmet Atilla, fully grasp the potential conflicts their lawyers have.

This story has been updated throughout.