In an effort to reshape Washington, Donald Trump has given the reins of his administration to the same special interests that he pledged as a presidential candidate to purge from the halls of power.

Trump promised to be a new kind of Republican, to avoid the moral hazard that he endlessly claimed would corrupt, or had already corrupted, not just his Democratic opponent Hillary Clinton but every one of his Republican primary rivals.

A Trump-led Washington would be different, he said. His administration would shun special interests. He was wealthy and politically self-sufficient. He didn’t need the lobbyist fundraisers or the corporate PAC contributions. He would win without them, and be beholden to none of them.

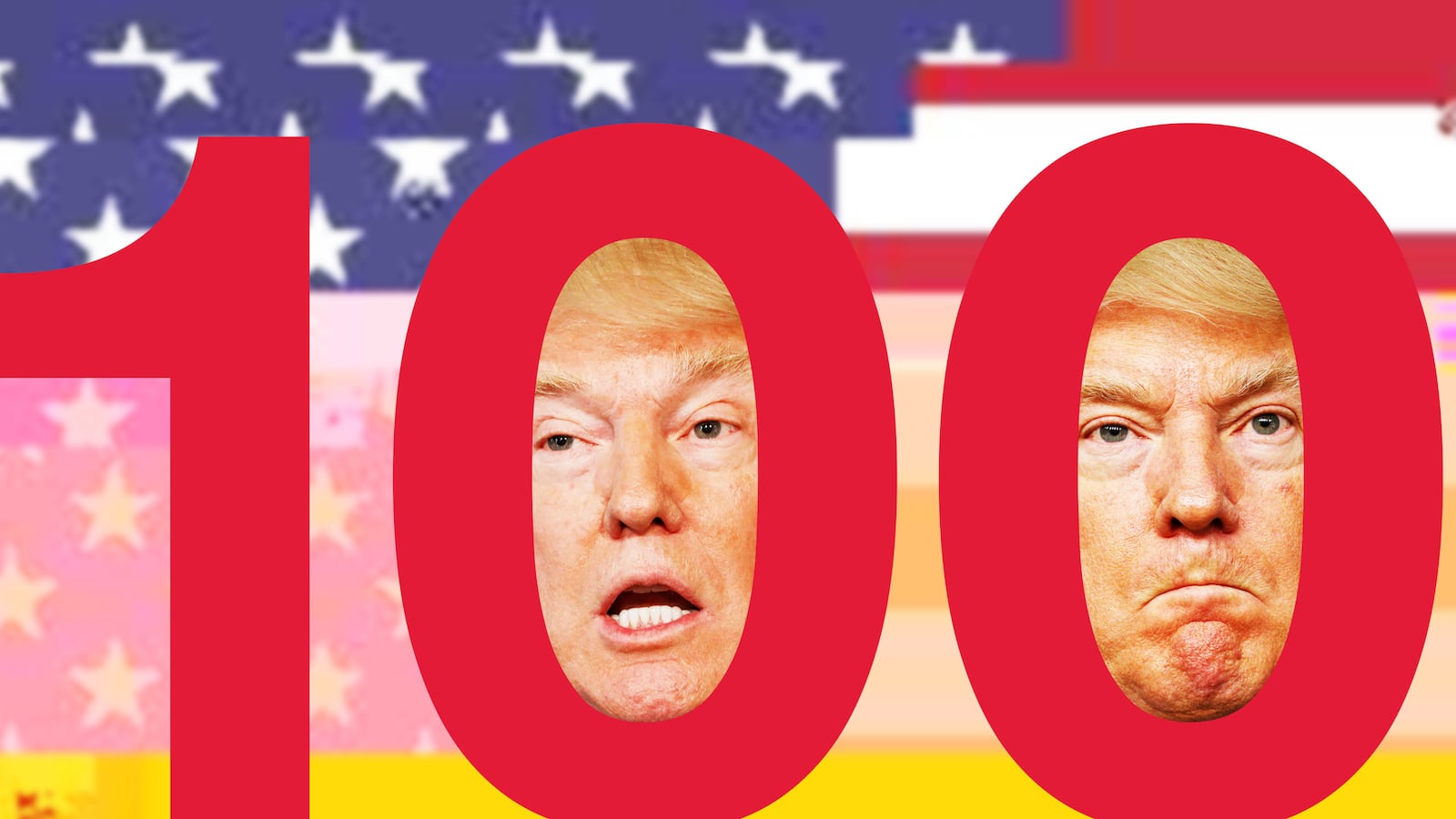

At the 100-day mark of his presidency, no Trump campaign promise remains more divorced from present reality than his pledge to “drain the swamp” in Washington. It’s a problem, in part, of his own making since the president’s brand of Republican politics all but requires him to violate his own standards for the staffing of his administration.

The resulting flood of lobbyists and business executives into the administration has led to some glaring discrepancies between Trump’s campaign rhetoric and early staffing decisions that appear to run afoul of the spirit if not the letter of campaign promises and ethics rules implemented by a January executive order.

Trump has stacked his administration with special interests not because he needs their money, but because he needs them, physically. A short-staffed administration desperate to fill high-level posts needs expertise in top positions, and Trump has fewer avenues for talent recruitment than other Republicans might.

Trump routintely railed on Wall Street during the campaign, then brought on veterans of investment banking giant Goldman Sachs to lead the Treasury Department and the White House National Economic Council. He derided the influence of lobbyists on the policymaking process, then secretly waived ethics rules so they could take high-level posts in his administration.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, in his previous gig as ExxonMobil’s chief executive, inked huge business deals with companies owned by adversarial foreign governments. At the Commerce Department, veteran steel investor Wilbur Ross administers trade policy that seeks explicitly to boost the steel industry.

Commerce is particularly illustrative of the pitfalls of the Trump administration’s hiring needs. As Ross pursues punitive trade actions against Chinese steel imports that compete with a company in which he was invested until January, the nominee to be his top international trade deputy, former steel industry lobbyist Gilbert Kaplan, is slated to impose the precise types of protectionist trade policies for which he has lobbied for years.

Trump’s explicit hostility to free trade puts him at odds with many conservative think tanks and academics, so drawing top Commerce staff from those groups, still ingrained with Reagan-era ideas about the free flow of goods, was never an option. So he turned to the private sector for top talent, and industry was happy to imbue the White House with its own policy preferences.

Trump has drawn on the Republican National Committee and other mainstream conservative and GOP outfits to staff his administration, but to fulfill the policy goals that set him apart from other Republicans, he has had to look beyond established Washington institutions and the agenda items that Trump derided as stale and outdated during the campaign.

It was a leading alt-right figure, white nationalist Richard Spencer, who pinpointed the precise problem that approach has created for the Trump administration.

“One fundamental problem of Trumpism is not so much Trump himself but Conservatism, Inc.: the think-tanks, the people, publications, etc.,” Spencer wrote this month. “Trump had a populist vision, but lacked an infrastructure to carry it out. He’s had to turn to all the same failed people and ideas.”

Whether or not those ideas have “failed,” Spencer is correct that the brand of America-First nationalism embodied by chief White House strategist Steve Bannon and embraced by Trump had a very shallow pool of political talent on which to draw.

Short of fringe groups such as Spencer’s National Policy Institute, from which even Bannon would surely decline to hire, there are no nationalist equivalents of Washington political and policy institutions such as the Heritage Foundation, the American Conservative Union, or the RNC, even if those groups and others have moved in Trump’s direction ideologically since his victory last year.

To the extent that Trump has tried to stack his administration with officials friendly to his nationalist political brand—which in large part rejects the post-Reagan conservative consensus and its accompanying D.C. institutions—he has been forced to draw staff from the private sector instead of organizations in Washington devoted in large measure to seeding talent for like-minded elected officials.

Whereas a Jeb Bush or a Marco Rubio might have drawn from a deep bench of conservative intellectuals and policy experts, Trump has been forced to in-source major segments of his policy team from the business community and D.C. influence industry, groups that are ostensibly restricted in what they can do in his administration.

Trump seems to have realized early on that, absent the types of staffing farm teams that might be available to a more conventional Republican, he would be forced to draw on the private sector—and the Washington influence industry in particular.

“You don’t like it, but your own transition team, it’s filled with lobbyists,” CBS’s Lesley Stahl noted in an interview with Trump less than a week after the election. “You have lobbyists from Verizon, you have lobbyists from the oil gas industry, you have food lobby.”

“Sure,” Trump admitted. “Everybody’s a lobbyist down there… That’s what they are. They’re lobbyists or special interests.”

Apparently recognizing that reality, Trump administration ethics rules eliminated an Obama-era provision that barred officials from serving in federal agencies that they had lobbied in the last two years. The result has been an explosion of high-level officials who share some of Trump’s nationalist policy preferences but have deep ties to an industry that might have prevented them from serving in the same roles for Trump’s predecessor.

For example, in his role at Commerce, Kaplan will, if confirmed by the Senate, be in charge of a policy agenda that prioritizes the precise policies that he pressed as a lobbyist in discussions with legislators and administrators, including staff at the department where he now works.

That work appears to directly contradict the language of the ethics pledge he will be required to sign upon taking office. Imposed by an executive order in January, it bars all appointees from participating in “particular matters of general applicability” that overlap with their previous lobbying work. The White House has said that it will consider waiving portions of the pledge if necessary.

It has reportedly already done so for officials at the White House and the Labor Department. But due to the opaque manner in which Trump’s ethics rules have been applied, there is virtually no way of independently determining whether an administration official has been exempted from those rules.

Under Obama administration ethics rules, the Office of Government Ethics was instructed to regularly update its website with notifications of waivers issued to administration officials. Trump’s executive order required no such disclosure, and a page on the White House website promising a list of waivers issued by the White House remains blank.

Instead, the administration has been secretly issuing waivers to numerous officials who would otherwise be barred from participating in major policymaking decisions due to their previous lobbying work, according to a recent New York Times report.

At the same time, former Trump confidantes are spinning the revolving door in the other direction, seeking to influence policy from the outside on behalf of paying corporate clients. Former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski is even marketing his lobbying services as protection against “tweet risk”—or the prospect that the president might say something bad about one’s company on his frequently caustic Twitter account.

The push by Lewandowski and others in Trump’s orbit to monetize their connections, and the lack of public information on who in the administration has been exempted from Trump’s ethics rules, creates natural demand for information on the people and organizations seeking to influence White House policy.

But on just that sort of transparency, Trump has upended previous practice in an effort to preserve some opacity in his White House’s communications with third parties. It announced this month that it would not publicly release White House visitor logs that recorded meetings with West Wing officials, making it more difficult to determine who is lobbying whom.

Trump’s pre-presidential rhetoric once again offered a stark contrast to his White House’s decision.

“Why does Obama believe he shouldn’t comply with record releases that his predecessors did of their own volition?” he asked in 2012. “Hiding something?”