LONDON—Sir Gyles Isham, MI5’s top man in Palestine and head of the security service in Jerusalem, was out of town on Monday, July 22, 1946, the day one of the 20th century’s most deadly terror attacks sent a wall of flame right through his offices.

Ninety-one people were killed as a powerful bomb devastated the southern wing of the King David Hotel, which served as the de facto headquarters of the British Mandate in Palestine and should have been the most closely guarded building in the Middle East.

Radical factions of the Zionist movement, some of whom openly described themselves as terrorists, were waging a relentless underground war to drive the British out and establish an independent state of Israel. But the mainstream organizations struggling to achieve the same goal apparently were horrified. In London, David Ben-Gurion, chairman of the Jewish Agency, told a reporter that the group behind the bombing was “the enemy of the Jewish people.” Scientist and statesman Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, was said to be in “an irrational frenzy of anger.” In Thurston Clarke’s 1981 book on the King David bombing, By Blood and Fire, Weizmann is quoted saying, “The Messiah will not come to the sound of high explosives.”

Among the dead in the shattered hotel were Britons, Arabs, and Jews, including Holocaust survivors, crushed beneath the rubble or blown to pieces. Such was the force of the blast that the head and some of the entrails of one victim remained for hours stuck high on the wall of the YMCA building across the street.

An entire corner of the King David Hotel was destroyed by the blast. (Fox Photos/Getty)

If Sir Gyles had been there, might he have seen something or done something that could have made a difference, either preventing the attack or investigating its aftermath? He could never know.

Less than 24 hours earlier, Sir Gyles had received an urgent cable dispatching him to foil an alleged assassination plot in Beirut which turned out to be bogus. And for decades, as revealed in a 1972 lettter, he was unable to shake the nagging feeling that something wasn’t quite right about that order to leave the city. Sir Gyles suspected that the radical Zionists who were behind the King David Hotel bombing had some part in getting him out of the way.

What he did not guess and probably could not have imagined was that a Soviet mole high in the upper echelons of the British Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, had played a critical role distracting Sir Gyles and his staff.

Then, as now, MI5 was charged with protecting the United Kingdom, its citizens and interests at home and overseas, while MI6 (SIS, the Secret Intelligence Service) gathers intelligence from outside the U.K.

The Daily Beast has discovered in recently declassified documents at the British National Archives at Kew in West London, that MI6 mole was deliberately disrupting the work of Sir Gyles and his colleagues who were left to chase faked or utterly implausible plots while very real and very deadly terror attacks took shape.

This revelation adds a new chapter to an extraordinary tale of treachery that has been at the center of many a spy novel, and offers a fresh perpective on the Soviet Union’s complex relationship with Israel.

What was the motive of the Soviet mole? He was almost certainly not inspired by the romance of the Zionist cause. Then (as now) the goal of the Russian secret services was to sow chaos and mistrust among their adversaries. World War II had ended just a year before, and the Cold War had begun. Not five months earlier, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill warned that “an iron curtain” had descended across Europe and the Soviets were probing the West’s defenses around the world.

By that summer of 1946, Britain was struggling to hold onto a crumbling empire. Just a year later, it would at last relinquish India, “the jewel in the crown.” And its grip on Palestine, mandated after World War I, had become much more a curse than a blessing as Jews, mostly immigrated from Europe, struggled to establish an independent homeland, and Arabs marshalled their forces to prevent them.

All that gave the Russians enormous opportunities to inflict pain on those who would, in Churchill’s words, “defend freedom and democracy” from “the indefinite expansion of [Soviet] power and doctrines.”

And Moscow could not have had a more perfect tool to weaken the British defenses than its man in London, MI6 section head and Russian mole H.A.R. “Kim” Philby, perhaps the most effective, and certainly the most legendary penetration agent in the annals of espionage.

***

The great British novelist Graham Greene, who had served in MI6 during World War II, knew Philby and liked him quite a lot, reminiscing about long, drunken Sunday lunches and the way Philby loyally defended his staff, even though “his big loyalty was unknown to us.” In fact, Philby’s treachery had led to the deaths of many British agents in many places, and Greene eventually noted Philby’s “chilling certainty in the correctness of his judgement, the logical fanaticism of a man who, having once found a faith, is not going to lose it because of the injustices or cruelties inflicted by erring human instruments.” Looking at the way Philby undermined and eliminated his rivals in the Secret Intelligence Service (a saga that would serve as the core of John Le Carré’s Smiley novels) Greene noted “the sharp touch of the icicle in the heart.”

Philby also had a longstanding and rather complicated personal interest in the Middle East. His father, St. John Philby, was one of the last of the great British explorers there. A convert to Islam, St. John had become a trusted adviser of King Abdelaziz Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia, and a bitter opponent of Zionism.

Early in Kim Philby’s career, in 1934, he had married a Jewish communist activist, Alice “Litzi” Friedmann in Vienna, where one of the witnesses to the small wedding was Teddy Kollek, later to be the long-serving mayor of Jerusalem. During the 1940s, as a senior official in the Jewish Agency’s intelligence operations, Kollek often liaised with MI5 and according to an authorized history of the British service, Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm, he helped to disrupt terrorist operations.

In August 1945, according the Andrew book, Kollek had told the British the secret location of a Jewish terrorist training camp near Binyamina and suggested it would be “a great idea to raid the place,” which led to 22 arrests.

Described as a "schmoozer" by Chaim Weizmann in an intercepted call recorded in the MI5 archives, Teddy Kollek was a daring intelligence officer decades before he became the celebrated mayor of Jerusalem. (John Cowan/Getty)

Philby must have known of Kollek’s role and presumably knew that Kollek might implicate him as a Communist agent. He certainly would have known that one of Kollek’s main contacts was Sir Gyles Isham, although precisely how Philby acted on that information remains unclear. At a minimum, he might have wanted to discredit Sir Gyles and his Jewish Agency liaison.

When searching for answers about Kollek and Philby and Palestine, in fact, one quickly enters the proverbial wilderness of mirrors. While there are many dossiers in the declassified files that touch on Kollek’s activities, many pages have been redacted, and several are marked “secret cross reference” to files labeled B.4.a.—which was the Soviet counter-espionage department.

Kollek would say, almost 40 years later, that he did finger Philby as a potential Soviet operative, but not until the 1950s, and then only after he came across him by accident while on a visit to CIA headquarters. Evidence that can now be gleaned at the archives in Kew suggests, however, that the revelation of Philby’s connections, and treachery, could have been made much earlier.

Kollek and Philby—former comrades from the communist milieus of Vienna—were working closely with the very same intelligence operatives active in post-war Palestine. Sir Gyles—who was so perturbed by Philby’s intervention before the King David Hotel bombing—had stayed with Kollek at his kibbutz in northern Israel a few months before the attack.

On several occasions in the intel files, Kollek was also described as being on very “friendly terms” with senior British officials such as the head of MI6 counterintelligence and his deputy, Maurice Oldfield (who later became head of MI6). They would meet for meals and drinks in London, exchanged letters and postcards, Oldfield even pledged to allow Kollek to leave Palestine for Europe in 1946 without alerting the proper authorities until Kollek was well under way. “I have kept my promise,” Oldfield later told his bosses back in London.

By 1947, Kollek was head of the Jewish Agency Intelligence Organization for the Anglo-Saxon world (basically U.K. and U.S.), so it was his job to know exactly who was who in MI5 and MI6. Is it really likely that Kollek never heard that a man whose wedding he had attended was working in the very same professional circles?

It may be the case that Kollek did not want to share the information with Oldfield and the others at MI6, and told instead an American spymaster, not a British one. After the “accidental” meeting at the CIA, he informed the CIA’s head of counterintelligence, James Jesus Angleton, about Philby’s background. But, as far as we know, Angleton did not act on the information—or did not seem to—leading to epic conspiracy theories.)

How Kollek might have used his privileged information in the years just before Israel won its independence in 1948 will remain unclear at least for as long as those pages in the archives at Kew remain redacted.

***

Despite much speculation in intelligence circles at the time about the role of the Soviet Union supporting the Zionist militants’ battle in order to destabilize the shaky British Empire, Philby’s own interventions have been largely overlooked.

It was known that Philby’s signature was on the memo that lead to the top intelligence and law enforcement officials leaving Palestine the day before the King David attack, but no other document had surfaced that would appear to support the idea that Philby was deliberately sabotaging Britain’s fight against Zionist terror operations—until now.

Among recently declassified intelligence files at the National Archives, The Daily Beast has uncovered another intel report distributed by Philby that can only be described as a classic disinformation play.

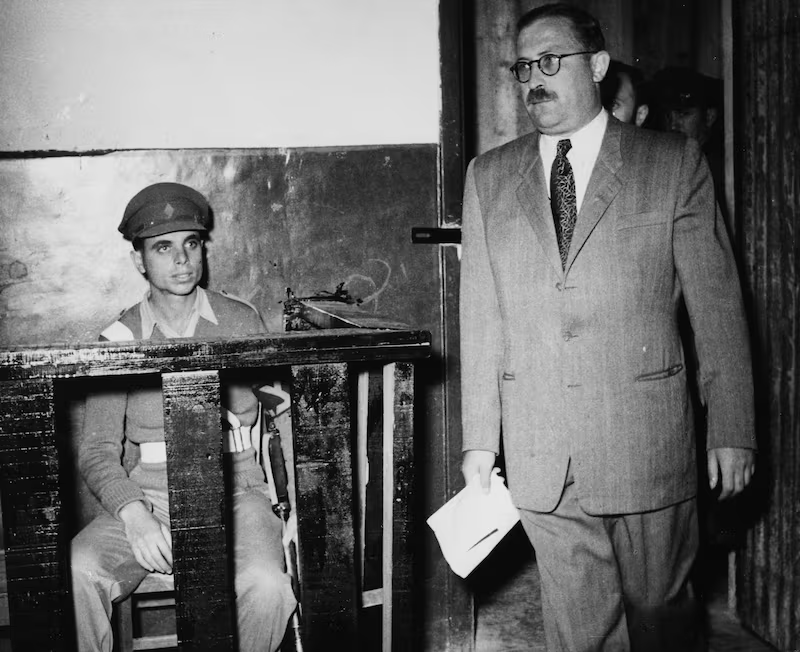

Out of the shadows, Kim Philby (on the right). (Keystone/Getty)

In a secret memorandum dated May 5, 1946, Philby made a highly unusual and rare personal intervention. He asked permission from MI5 to disseminate to stations across the region a ludicrous intelligence report that detailed a plan for a French soldier to parachute into Palestine in order to seal an arms deal with the terrorists.

The official MI5 historian Prof. Christopher Andrew told The Daily Beast that spreading this kind of blatantly false information to confound his colleagues in the British intelligence community was “typical Philby mischief-making.”

The supposed plan by perfidious France made no sense at all. Precisely because the French had excellent existing relationships with the Jewish underground in Beirut and even Paris—where the two main guerilla groups had their European headquarters—the notion that the French would be parachuting one of their soldiers into British-controlled territory was ludicrous.

It is hard to conceive any motive for Philby to spread word of this so-called plot other than his desire to send his colleagues on a wild goose chase.

For some more perspective on Philby’s intervention, I emailed details of the memo to one of America’s leading terrorism experts. Professor Bruce Hoffman, director of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and author of Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel 1917-1947, has studied Zionist terror groups in Palestine for more than 40 years. He is a former scholar-in-residence at the CIA; author of the authoritative Inside Terrorism; and served on the U.S. government’s 9/11 Commission.

When we caught up on the phone a few days after my email, it became clear that this new document might indeed be important. “I’m kinda bursting,” he said “I think you’re on to something with Philby!

“It was fascinating what you wrote because it does make sense in a bigger picture. You can see the motive for the Soviet Union—now that you have more of it—you can see, perhaps, what Philby is doing.”

Hoffman noted that the Soviets were keen to keep London preoccupied in places like Palestine so it would not focus on the growing battle between East and West in Europe.

“You can see a definite appeal for the Soviet Union: to divert Britain’s attention from the center to the periphery. And, of course, stirring the pot with these terrorists, is a great way of doing so,” he said.

***

Today, “terrorist” is not a word commonly associated with British or American discourse about the Zionist movement. But in the 1940s, the term often was applied to two specific organizations. One was the Irgun Zvai Leumi (National Military Organization), commanded by Menachem Begin, which carried out the King David Hotel bombing. The other, even more radical splinter group called itself Lehi, a Hebrew acronym for Fighters for the Freedom of Israel. The British called it, pejoratively, “the Stern Gang,” after its founder, Avraham “Yair” Stern. But the British shot him dead in 1942, and one of its operational chiefs became Yitzhak Shamir.

Both Begin and Shamir eventually became prime ministers of Israel, but that was many decades later.

The two organizations, Irgun and Lehi, carried out a series of bombings, ambushes, and assassinations targeting the British and their associates. In November 1944, Lehi assassins directed by Shamir murdered Lord Moyne, Britain’s secretary of state for the colonies and, as minister resident in Cairo, London’s top official in the region. The killers, as it happened, used a Russian gun.

According to Calder Walton, a historian of intelligence at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, Lehi was one of the last groups in the world to openly describe itself as a terrorist organization. It was also a crucial inspiration for other the international terrorist groups with other causes that would flourish in the coming decades, although most of them followed the lead of Begin and the Irgun who described themselves not as terrorists but freedom fighters.

“This is the start of something new: the fusion of modern nationalism with political violence that spills over borders,” Walton told The Daily Beast.

The cat and mouse game between the Zionist networks and British intelligence services continued through World War II and for three years after—until Britain finally relinquished its League of Nations mandate to control the territory.

What could the Russians do to encourage the violence and unrest? What could Philby do?

For starters, many of the operatives hailed originally from what would was, by 1946, Soviet or Soviet-dominated territory behind the Iron Curtain. A top secret memo prepared by British spies described Lehi as being dominated by Eastern Bloc émigrés. “Most of the members were Jews of Polish, Russian and Bulgarian origin,” the MI5 analysts concluded.

Lehi and the Irgun had networks all over the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. Lehi and the Irgun, as noted, based their European networks out of Paris, where both groups were led by men born inside the USSR itself. This did not, of course, mean that their allegiance must be to Moscow, but it did lay the groundwork for contacts.

According to another recently declassified MI5 analysis: Monia Bella headed up the Irgun’s European operation while Yaacov Eliav held a similar position for Lehi.

Eliav’s boasts that he had invented the letter bomb helped him to establish a reputation as a ruthless bomb-maker known as the “the Dynamite Man.”

One of his closest accomplices was Betty Knut—the glamorous daughter of a noble Russian family, who had fought the Nazis alongside the French resistance before switching her allegiance to the Lehi and the battle to force Britain out of Palestine. She was the granddaughter of famous Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, who was related to Stalin’s Communist Party right-hand man Vyacheslav Molotov—although perhaps not as closely as contemporary newspaper reports or Lehi legend would have you believe.

While their brethren wreaked havoc in Palestine, Lehi’s Parisian HQ became the base for attempts to strike Britain on home soil. One of their most daring plots was cooked up by Eliav. Explosives manufactured in France were smuggled into Britain sewn inside clothing, including the shoulder pads of a coat.

Knut was to be the bomber on April 17, 1947.

Dressed immaculately in a fine hat and furs, that helped conceal the bomb, she approached the grand entrance to the Colonial Office, a mansion built in the 1750s, which is a few yards to the north of Downing Street in Westminster.

She asked the guards if she could use the facilities, but security was relatively high after previous Zionist terror attacks and the guards initially turned down her request when she admitted that she had no identity papers.

Knut later explained that she had persuaded the guards by saying: “I’ve heard that Englishmen are gentlemen, yet here is a woman who needs a few minutes of privacy, and you are asking her to show papers just so you will know how old she is.”

The men relented and allowed the would-be killer right into the heart of the British government. She planted an explosive device in the toilets before slipping away. Fortunately, the bomb failed to detonate and it was discovered by a member of the cleaning staff.

During a recently declassified briefing given to Scotland Yard officers in 1948, an MI5 officer described Isaac Pressman as the only British citizen linked to Zionist terror groups who had managed to acquire explosive materials inside Britain. Twenty-seven grenades were discovered in his modest flat in Stoke Newington, a neighborhood in North London, which MI5 officers believed he had stolen from an RAF airfield in Wiltshire.

Like the leading Zionist militant figures on mainland Europe, Pressman had also been born inside the USSR.

***

With so many actors from the Soviet Union, it’s hardly surprising that British and American intelligence agencies suspected that there were Communist links to the terror groups.

In the later years of World War II and the immediate aftermath, it was notoriously difficult to travel across borders in Europe, and immigration to Palestine was strictly controlled by the British, yet some Zionist leaders continued to disappear from the East and resurface inside the British mandate.

Sir Percy Sillitoe, the director general of MI5, mused on the subject during a series of letters that pinged back and forth between HQ and Dick Thistlewaite, MI5’s man in Washington, who was responsible for liaising with the FBI and the CIA. (A few years later, that would be Philby’s job as well.)

Moshe Sneh, was a Zionist from Poland who was apparently captured by the advancing Red Army before escaping from a camp in the USSR; Sir Percy wrote: “It is interesting to speculate what SNEH’s experiences were as a prisoner of the Russians and whether his ‘escape’ in March 1940 was genuine or engineered by the Russians for their own purposes.”

Sneh would go on to be appointed head of the Haganah, the paramilitary wing of the mainstream Jewish Agency, before eventually becoming a Communist politician in the years after the independent state of Israel was established.

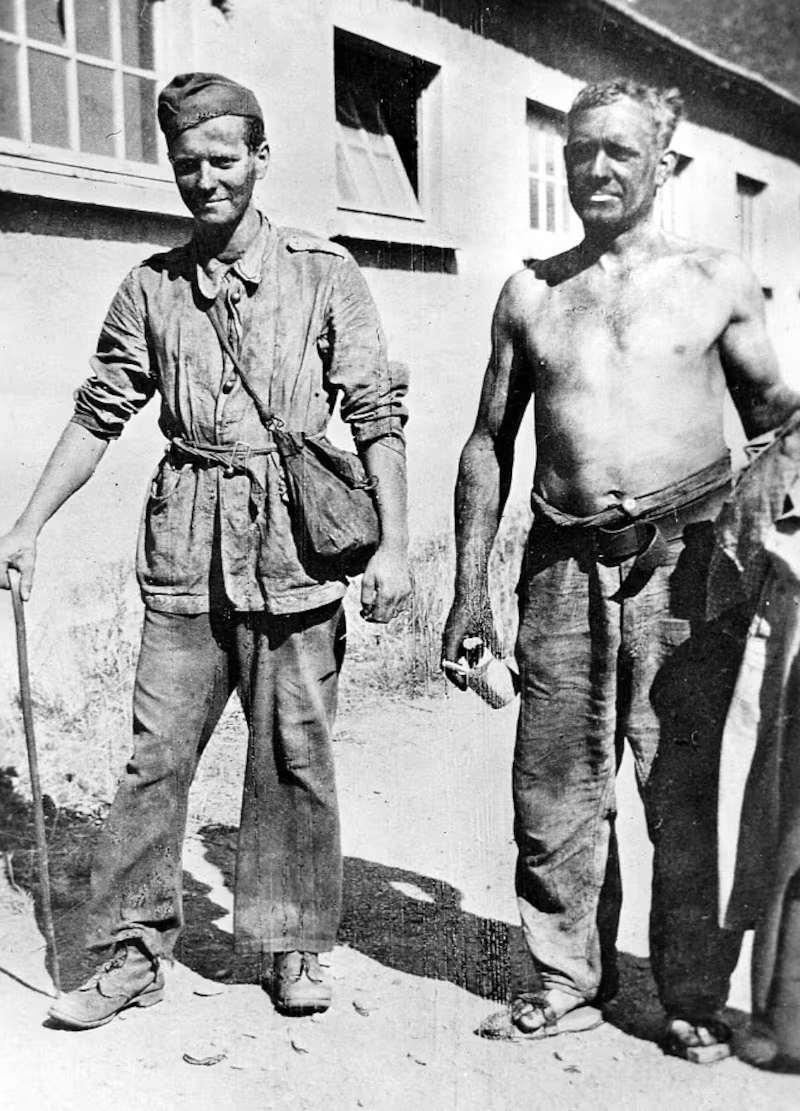

Menachem Begin came to the Middle East via a similar route, arriving on Palestinian soil after being allowed to escape one of Stalin’s gulags.

The Polish émigré grew up in Belarus in the Soviet Union before he was rounded up by the NKVD as a Zionist during the war. He was convicted of sedition without trial and condemned to eight years in the gulag. After a deal with the Polish government in exile following the collapse of the Nazi-Soviet pact in 1940, he was allowed to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East, which was created in the USSR and funded by Moscow. Stalin agreed to allow the army, which contained an estimated 4,000 Polish Jews, to march down through Persia to Palestine. Once in the Middle East, Begin was discharged by the Polish Army and soon rose to the top of the Irgun.

His Polish compatriot Nathan Yellin-Friedman also escaped from the Russians only to surface in Palestine where he became one of the leaders of Lehi. Yellin-Friedman, like Shamir, was personally involved in plotting the assassination of Lord Moyne.

Despite the speculation, Britain never publicly accused the Soviets and their allies of sending Zionist leaders or trained fighters to disrupt the British mandate in Palestine. But newly declassified intelligence reports show that MI5 believed it had enough evidence to prove that the Polish Army, which was formed in the Soviet Union but was mainly staffed by anti-Communists from the old Polish forces, was doing more than turning a blind eye to illicit Zionist travelers—it was secretly working to help establish a terror group that would undermine the British.

Alex Kellar—a flamboyant MI5 officer believed to have inspired John Le Carré’s “man in the cream cuffs”—produced a report after a visit to the region in February 1945 that concluded: “The part deliberately played by the Polish Army Intelligence in building up the Irgun, an activity which has long been suspected, has recently been conclusively established from an XXX source which has disclosed the name of five Revisionist Jews, among them BEGIN, who were released a year ago by the Polish Army in the Middle East for ‘political and propaganda’ purposes.”

The Polish Army was in no way beholden to Moscow but Stalin’s decision to set up the army and then let it march to the Middle East was a huge help to the Jewish underground.

And if destabilization was the aim, the Polish Army’s intervention proved to be a masterstroke.

The Polish Armed Forces in the East was populated by people who were allowed to escape Soviet internment. (Handout)

***

Newly declassified letters home to London from the head of the MI5 delegation in Jerusalem—published here for the first time—show just how despairing the British had already become by the spring of 1945.

After a mortar came within 25 yards of the police headquarters in Jaffa, and two more landed in the Sarona police camp, Lt. Col. Henry Hunloke sounded broken even though no one had been hurt. “The usual hopelessness has fallen on me as to what on earth we can do to these brutes,” he lamented to Alex Kellar.

Remarkably, the Irgun and Lehi also seemed to have convinced Hunloke that their deadly attacks were supported by the Jewish people in the Palestinian territories as a whole, a judgment that may also have reflected a deeper anti-Semitism.

“I consider it entirely wrong to lay the blame on any single section of the Jewish Community. By their teaching of the youth, by the speeches of their so-called leading politicians, they are all equally culpable,” he explained in another previously unpublished letter to Kellar.

More serious study of the Jewish population in Jerusalem suggested that these terror groups did not enjoy widespread support. A “Middle East security summary” drafted by British officials in April 1946 concluded: “The Stern Group is still unpopular among the general public. This was very much in evidence when in contrast to a funeral gathering of many thousands in Jerusalem to attend the funeral of a Haganah member killed on the wide-scale operations on the night of 16/17 June, no one attended the funeral of 11 Stern group members killed after the Haifa raid.”

Hunloke’s willingness to ascribe a single motivation to an entire people also was indicative of a growing British sense of panic about the situation on the ground.

Global opinion was turning against Britain’s mandate in Palestine and it was becoming increasingly difficult to prevent “illegal” Jewish immigration. Britain was forced to increase its military presence until it had 100,000 troops stationed in Palestine, and yet still there were weekly attacks on British police officers, civilians, and a campaign of infrastructure destruction.

Some of the attacks were so brazen that Britain was left looking weak and foolish on the world stage. In May 1947, Irgun operatives disguised in British uniforms blasted a hole in the wall of a British prison in the northern coastal city of Acre and helped 28 Irgun and Lehi prisoners escape, while a series of traps and blockades prevented British reinforcements reaching the scene.

Three Irgun operatives eventually were caught and executed by the authorities for their part in the prison break. In revenge, the Irgun kidnapped two British police officers, murdered them, and left their bodies hanging in a booby-trapped eucalyptus grove.

After the grueling World War II, Britain’s appetite for more violence was waning, and so were its coffers. There is be no doubt that the relentless terror campaign helped force London to back down. In May 1948, Britain officially began to limp out of the Mandate.

As CIA analysts put it with admirable understatement in documents that were published for the first time at the end of last year (PDF): “The strategic value of the country to the British has been offset by administrative difficulties.”

The problems posed by the terror groups were considered overwhelming in London by 1947. But for years the Irgun and Lehi had had to struggle for funding and weapons. The birth of the Cold War had put the quest for weapons, money and influence in Palestine into the context of a battle for supremacy between two superpowers.

In his 1968 memoir My Silent War—which he wrote after escaping to Moscow (and for which Graham Greene penned the introduction)—Philby emphasizes Russia’s engagement with the Middle East, a region where he worked in semi-retirement from 1956-63. “The Soviet Union is interested in a very wide range of Middle Eastern phenomena. Enjoying a wide margin of priority at the top of the list are the intentions of the United States and British governments in the area.”

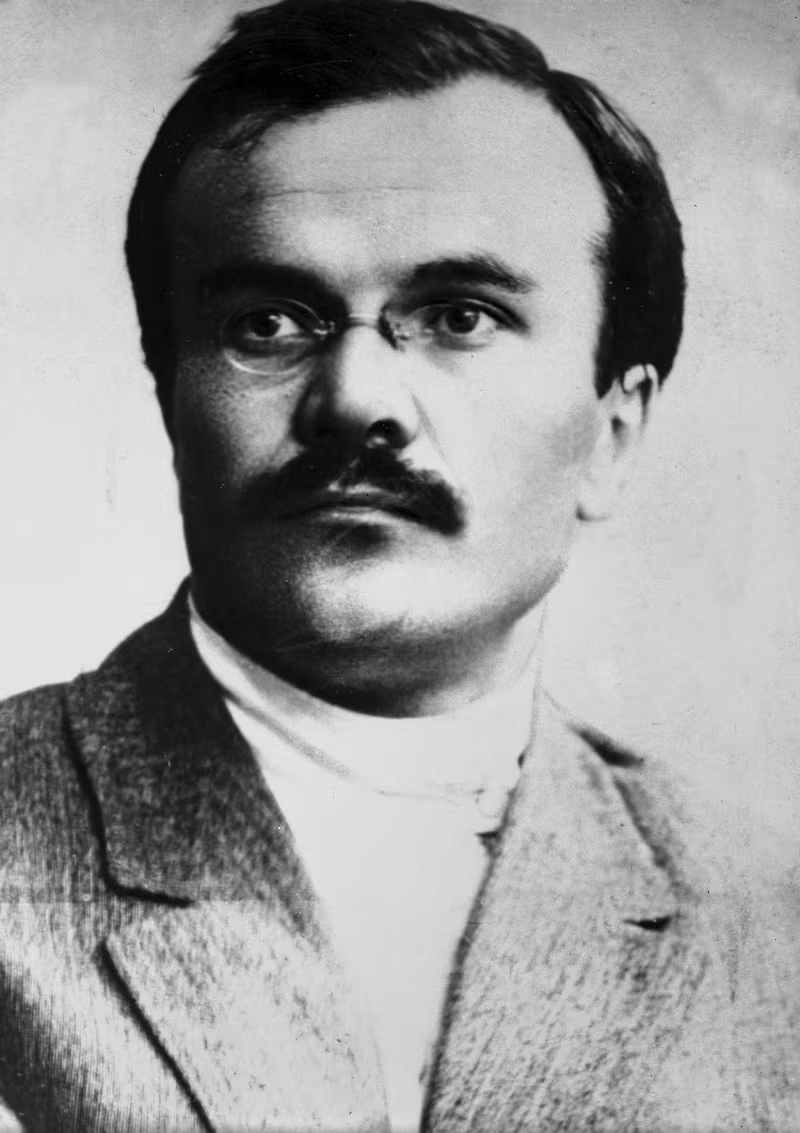

Nathan Friedman-Yellin was one of the first Zionist leaders to recognize that coming battle between East and West, according to Joseph Heller, one of the most respected Israeli scholars on the history of the Jewish underground. As one of Lehi’s leaders, Friedman-Yellin first began thinking about—and tentatively advocating for—the possibility that the USSR would become a serious sponsor of Lehi’s paramilitary aims in 1943.

Nathan Friedman-Yellin advocated a switch of focus towards the East for Zionist support. (Keystone/Getty)

This was a remarkable prospect given the history of the Zionist militant groups which had formed out of the right-wing Revisionist movement in Poland.

The politics of Lehi’s founder, Avraham Stern, unquestionably belonged to the extreme right wing. Indeed, he even offered to cooperate with the Nazis and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, whose troops were advancing through Egypt in 1940. He made the extraordinary calculation that his enemy’s enemies should be his friends—despite the anti-Semitic atrocities being carried out under the orders of Adolf Hitler.

But in the years after Stern’s death in 1942, Friedman-Yellin began dragging Stern’s gang to the Left. By the following year, Lehi had adapted one of Karl Marx’s most recognizable slogans: “Each gives to the nation according to his ability; each receives from the nation according to his needs.”

The transformation gathered pace as the Red Army continued its formidable march West across Europe in 1944. Friedman-Yellin claimed he could see “signs” of Moscow’s attitude to the Zionists warming as he foresaw a moment when the Jewish underground and the USSR could be united in their antipathy for Britain. He and some fellow Sternists began to talk of a Hebrew National Bolshevism—which was partially aligned with Soviet policy but claimed to have roots among right-wing European radicals as well as those on the Left.

At this stage the Irgun remained far more circumspect. In common with the official Jewish Agency and their paramilitary wing Haganah, they stated that they would not break with the British at least until World War II was over.

It was in the early postwar years that British intelligence began to suspect that much of the Zionist movement was beginning to look to Moscow for inspiration or even direct help.

In a newly declassified speech to police officers in Britain, a senior MI5 official explained: “It is impossible to ignore the fact that certain of the left-wing political groups in Palestine under the leadership of Moshe Sneh, the former commander in chief of Haganah, are watching the advantages to be gained by an approach to Soviet Russia, while in the background both the Irgun Zvai Leumi and the Stern Group have echoed this policy in their secretly printed newspapers.”

Another recently declassified intelligence agency dossier, included a telegram that quoted secretly printed Lehi pamphlets from 1947 calling for “a re-orientation of Zionist policy to bring it into line with Russian aims against British imperialism.” A telegram from the file was sent from Palestine to the secretary of state for the colonies, Arthur Creech Jones, on May 27 that year. It reported a growing co-operation between the local Communists and the Zionist extremists.

“A noticeable feature has been the dissidents’ and particularly the Stern Gang’s tentative approach to the Communists, in return for which the latter, doubtless on instructions, have ceased to inveigh against ‘Fascist criminals’ of the Jewish Underground.”

Heller said it was no surprise that Lehi would have struck a deal with the brutal Stalin regime if they thought it would help them realize the dream of founding Israel. “In 1940 they believed they could ally with Hitler, and in 1947-1949 with Stalin—with a Jewish state stretching on both sides of the River Jordan!” he told The Daily Beast. “They would have allied with Satan himself.”

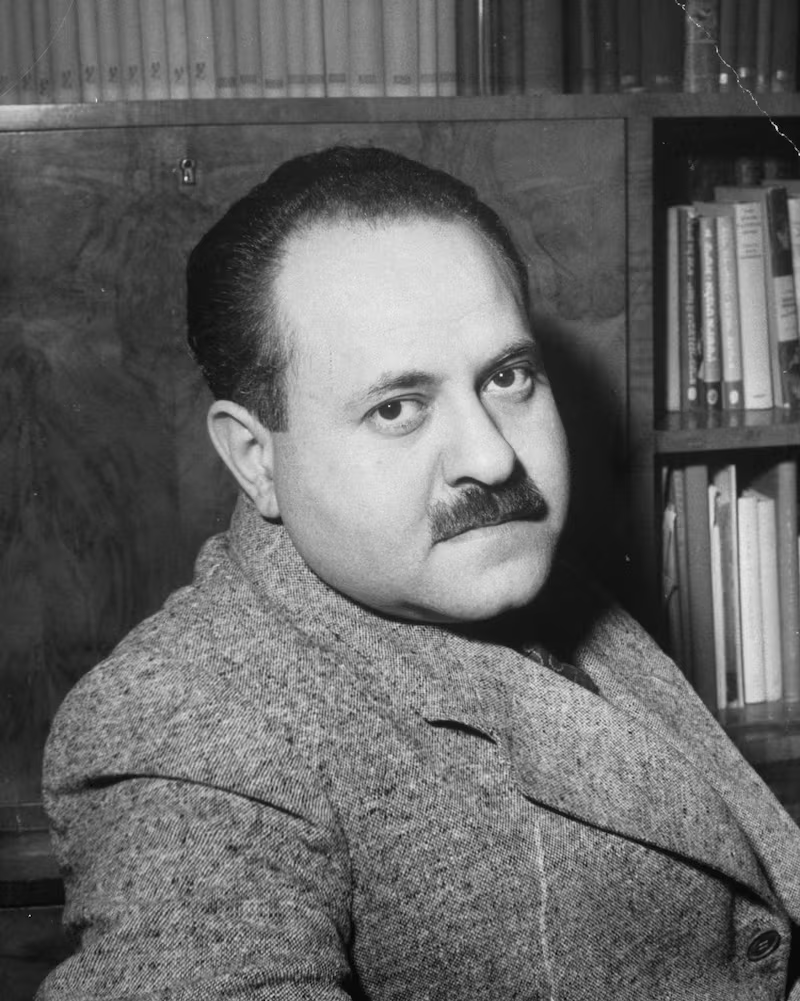

Moshe Sneh was recently named as a Russian source in secret KGB files. (Dmitri Kessel/Getty)

By 1947, Moshe Sneh, who lead the Haganah during its most aggressive period of activity against Britain, was giving underground speeches in praise of the USSR. British police officers in Palestine reported that they intercepted a call in which “SNEH is further alleged to have stated that in Soviet Russia they had a great neighbor behind their doors, and that Russia was the only power which is fighting Anti-Semitism.”

An intercepted letter dated November 1947 from Samual Lev Hacohen in Paris to Moshe Kolodny, a Jewish Agency executive in Jerusalem read: “This letter is very confidential and you should tear it up after reading… I spoke with Dr. SNEH after his return from Roumania. His Russian ‘orientation’ keeps growing steadily… He seems to dream about a large pro-Russian party… I think that the result of this ‘orientation’ will be that he won’t be able to remain in the General Zionist Party for long.”

***

So some of the Zionists were leaning towards Moscow, would the Communists respond in kind?

The overwhelming reputation of the Soviet Union as almost pathologically anti-Semitic would suggest that was impossible. During the so-called doctors’ plot in 1953, for example, a group of predominantly Jewish physicians were falsely accused of a conspiracy to murder Soviet leaders in Moscow.

KGB documents smuggled into the West by Soviet archivist Vasili Mitrokhin, which were fully opened to the public for the first time in 2014, offer an unprecedented glimpse into the minds of the men running the Soviet intelligence apparatus.

The first investigative reporter to immerse himself fully in the Mitrokhin files on Israel and Zionism told The Daily Beast from Tel Aviv that he was stunned by the scale of the anti-Semitism and the extent to which Jewish conspiracy theories were a founding principle of the Cold War itself.

“One of the things that surprised me most when reading all these documents was how profound was the belief of the chief of the KGB in the unbelievable power of the Jews,” said Ronen Bergman, whose book on the Israeli security services—Rise and Kill First—will be published later this year.

“It was not clear who was the dog and who was the tail. Some of the KGB were heavy believers in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion—therefore it is not the United States that is controlling Israel, it’s the ‘world Jewry,’ who is controlling the United States and Israel. Israel is just another tool of the ‘world Jewry.’”

The discredited Protocols—the most notorious literary hoax of the 20th century—claimed that there was a secret plan for global Jewish domination. Russia’s security services apparently believed these absurd notions, first promulgated under the tsarist regime, for decades after the Bolsheviks took power.

Given its history of virulent anti-Semitism, it’s extraordinary to think that the Soviet Union was one of the leading sources of support for the fledging independent state of Israel. But that is exactly what happened.

“There is no doubt that the Soviets helped the Zionist-Israelis before and during the war of independence,” Heller said. “I do think they assisted the Zionists in Palestine a great deal both militarily and politically.”

As a matter of public record, the Soviets backed Zionism at the United Nations and then became the first country to recognize an independent state of Israel on May 17, 1948. As war raged, after the partition plan approved by the United Nations in November 1947, the Soviets poured weapons in through the satellite state of Czechoslovakia to arm the Haganah, as well as the Irgun and Lehi, who had now joined forces to protect the fledgling country during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

A CIA file from 1949, which was declassified in 2013, (PDF) confirmed that the U.S. had been a junior partner when it came to military backing for the new state of Israel.

“During the 1948 UN-imposed truces, the Israeli armed forces received sufficient arms and military equipment from clandestine sources abroad, chiefly from Czechoslovakia and, to a less extent, indirectly from the US, to enable them to transfer their initial military inferiority into a definite superiority.”

The importance of the link between Soviet Czechoslovakia and newly independent Israel has largely been played down by both sides but it began with negotiations between Sneh and the communist satellite’s deputy foreign minister in July 1947.

The weapons would eventually include around 50,000 rifles, 6,000 machine guns and 90 million bullets, as well as 25 fighter planes which were smuggled into the country in pieces.

The depth of the Soviet backlash against Israel in later years can partly be ascribed to Moscow’s disappointment and fury that its assistance was not rewarded with closer ties in the years after independence.

The timing of the Kremlin’s decision to back Israel has been hotly contested.

Calder Walton, who examined Britain’s intelligence service in the Postwar era for his book Empire of Secrets, said that while it was widely accepted that Moscow assisted some Zionist groups before the creation of Israel—it is thought that the Soviet policy towards the Zionists had not yet crystalized by the time Philby was interfering from inside the British security service.

A document highlighted by Heller in Superpower Rivalry, published in November, however, demonstrated that “the Soviet Ambassador to London announced in 1943 that they would support Zionism”—which is several years earlier than previously thought.

That document can be found in a collection of papers released jointly by the Israeli and Soviet governments, which includes the minutes from a meeting of the Jewish Agency in London on Sept. 14, 1943. It details the conversation between Chaim Weizmann, who would become Israel’s first president, and Ivan Maiskii, the Soviet ambassador to London, who was soon promoted to become deputy commissar of Foreign Affairs responsible for post-war planning.

Chaim Weizmann was one of the most celebrated early Zionists and would eventually become Israel's first president. (Bettmann/Getty)

Weizmann reported back to his colleagues that Maiskii “replied that he could not commit his government, but he believed that the Soviets would support them… He thought that Russia would certainly stand by them.”

Maiskii’s main reservation apparently concerned the availability of viable, habitable space for a Jewish state in Palestine. Ben Gurion, who would become Israel’s first prime minister, took the Russian official on a tour a few weeks later, which he believed had impressed Maiskii. “He asked questions and probed about the kibbutz. I had felt in London that he thought we were making things up, because we are doing something they don’t dare do in Russia. He was very impressed by the place; he was amazed when he saw forests, fruit trees and more,” he reported to a meeting of the Jewish Agency Executive in October 1943.

If Russia was broadcasting its nascent Israel policy to London in 1943, Philby almost certainly would have known about it and concluded that his covert assistance to the Jewish underground would be acceptable—or even commendable—to Moscow.

***

Deep in existing Russian files and dossiers there may be definitive answers about the Soviet relationship with some of the Zionist terror organizations, or at least some of their members. But, says Heller, “It is difficult to give straight answers” because Russian President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB agent, “refuses to open the archives.” In addition to the Mitrokhin cache, Boris Yeltsin had begun to open up access to Russia’s historic secrets but Putin slammed the door shut.

The latest tranche of documents about British intelligence on the Zionist underground that have been declassified in London show the Western services attempting to evaluate the level of Soviet assistance at the time.

A dispatch from April 1948 lists some of the reports the British had collated over the previous six months: Lehi (or the Stern Gang) using Russian weapons in August 1947; Russian aid sent to the Irgun the same month; Polish support for the terrorists two months later; and contacts between Lehi and the USSR or Soviet agents in October 1947 and April 1948.

“We do have a considerable amount of information which indicates that the Stern Gang, in particular, look to the Soviet Union for support rather than to the Western Powers,” the analyst concluded. But these were based on allegations and uncorroborated reports by third parties, and the conclusion was cautious: “We have… seen no hard evidence that Jewish Terrorists have in fact been in contact with Soviet agents or have received money or arms from the USSR or Soviet satellite powers.”

What is abundantly clear from the dossier is that the Jewish Agency—the mainstream Jewish authority in Palestine, where Teddy Kollek was a key liaison—consistently told the British that Lehi was being given assistance from the USSR. MI6 reports explain that Lehi was “regarded by the Jewish Agency as definitely under Soviet influence.”

The Jewish Agency was often Britain’s best source on the guerilla underground movement—at times providing names of active terrorists—but there were also periods when the Agency was working alongside the guerilla groups against Britain’s rule in Palestine.

In October 1947, MI6 officers reported back to London that they had been passed details by the Jewish Agency of a meeting between the Irgun and Lehi, which they still called the Stern Gang, during which terms of engagement against the British in the wider region—with Soviet support—had been discussed.

“To this end numerous groups of members of both organizations would penetrate into Iraq and Syria where they would enjoy the support of pro-Soviet bodies, mainly among the Kurds. Soviet agents would supply money, arms and explosives.

“The Stern Gang declared that the U.S.S.R. had undertaken to support terrorist action against the British in Palestine from any quarter. The I.Z.L. [Irgun] agreed to the principles outlined, but reserved a final answer until later.

“The resulting involvement of the I.Z.L. (through the Stern Gang) into the Soviet sphere of influence has disturbed the Haganah.”

More and more detailed reports about military, training or weapons assistance from the Soviet sphere continued to be collected, however.

In July 1948, MI6 reported that a Yugoslav militant was “employed as instructor in sabotage operations” for Jewish communists and in touch with Lehi. Two years earlier, intelligence reports—now documented for the first time—described “a secret organization,” headquartered in Constanza on the Black Sea coast of Romania, “created for the purpose of selecting and training native and foreign Jews in terroristic activities and sending them to Palestine.”

Perhaps the most far-fetched intelligence report—declassified in an earlier tranche at the National Archives in London—originated from an FBI investigation into Moshe Sneh’s time in New York. The report alleges that Sneh was receiving payments from Russia channeled through the Irgun from October 1946.

This report is given little credence at the time; although Bergman’s Mitrokhin archive investigation revealed late last year that Soviet agents in Israel were sending reports to Moscow in the 1950s based on information they said they had be provided to them by Sneh.

Sneh’s son Efraim, an Israeli politician, said in response, “This never happened.” And denied that his father had been a KGB agent.

Formal talks between Lehi representatives and a Cominform representative in Czechoslovakia began soon after Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko announced Russian opposition to British imperial control of the Palestinian mandate at the United Nations in 1947. The following year, Soviet weapons arrived—via Czechoslovakia—to bolster Stern, Irgun and Haganah fighters now united to defend the fledgling state of Israel.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Lehi was all too happy to emphasize its contacts with the Soviets because it saw Russian support as a crucial step in establishing Israel—and its own part as crucial in luring Moscow to pick a side.

In a Stern Radio broadcast on May 27, 1948, one of the group’s propagandists boasted: “The Soviet attitude [that Zionists were British lackeys] did not change until the appearance of the fighters for the freedom of Israel [Lehi] who started the war for the liberation of the Jewish homeland from the foreign yoke.”

***

Yisrael Medad is a director at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center—so perhaps more loyal to the Irgun’s version of events than Lehi’s—but he concurs with some of the Lehi version. Asked by The Daily Beast if the splinter group had secret ties to the Soviet Union, he said: “Of course Lehi did. A delegation arrived in Palestine in 1947 to meet and assure arms deliveries and Lehi had strong contacts in Bulgaria (shared childhood school chums).”

Medad repeats the Lehi claim—still posted in its official history—that Yitzhak Mirkin, a Lehi leader, had saved the life of the man who became the Communist Party chairman (i.e., leader) of Bulgaria, Georgi Dimitrov, who had a strong relationship with Stalin. According to the version of events that you read, Dimitrov secured for Mirkin an audience either with a personal emissary of Stalin or Stalin himself.

There may also have been a meeting between would-be bomber Betty Knut and then-Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov in Paris. The supposed secret summit is listed in the terror group’s online history.

Could Betty Knut really have met this man—Vyacheslav Molotov—in Paris? (Harlingue/Getty)

But Professor Heller says there is no hard proof to substantiate these direct links.

“Although former Lehi members insist that they were supported, for example by some communist leaders such the Bulgarian leader Dimitrov, or through Betty Knut; there is no primary source which would prove it!”

Even if there were no such meetings, however, that would not have precluded Kim Philby’s “mischief-making.” And what we have now for the first time is evidence that this Soviet mole in Whitehall was able to wage a disinformation campaign that helped to thwart or confound Britain’s ill-fated battle against the Zionist guerillas. Which also brings us back to Sir Gyles.

***

H.A.R. Philby was head of Section IX: which was responsible for Soviet counterintelligence and Communism—protecting Palestine was not specifically part of his brief but, as Sir Gyles Isham found to his chagrin, he was in a rare position of power to influence British intelligence work all over the world.

In 1972, Sir Gyles wrote a letter wondering if the Irgun had somehow contrived for him to be absent from Jerusalem the day the King David Hotel was bombed. It is quoted in Bruce Hoffman’s authoritative book on the Revisionist militants Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel. Hoffman told The Daily Beast he had found it by a “stroke of luck” among Sir Gyles’ papers, which had been left to the archive in Northamptonshire at the end of a long career.

Born into an aristocratic family, Gyles Isham had been attracted to the theater as a young man, and before his wartime stint in the foreign service, he had appeared as an actor in several films, including Secret Lives and Under Secret Orders, and one, The Iron Duke, in which he played the czar of Russia. After his time in the foreign service, Sir Gyles became a local politician and trustee of the National Portrait Gallery.

His papers are housed in a drab single-story municipal building on the ring road south of Northampton in central England.

Sir Gyles had been defense security officer in Palestine from October 1945 to November 1946, and in another letter to a former comrade from his army days he described that period in Jerusalem as “a more dangerous time” than his active military service during World War II.

His letter about the King David Hotel bombing was sent to Sir John Shaw, the former chief secretary of the Palestinian Mandate, who was one of those left scrabbling through the wreckage of the hotel looking for friends and colleagues after the blast.

Sir Gyles wrote that the proximate cause of his absence was a directive to investigate an assassination plot in Lebanon. He and a colleague “were asked to go to Beirut to warn [the British minister] and to see what we could do with the Lebanese Police. We did know that a number of the members of the Irgun were in Beirut.”

Looking back at the original trail of correspondence at the National Archives in London it seems that Sir Gyles and the MI5 operatives in the Middle East had been irritated, at the time, that Philby had gone over their heads by writing directly to the Foreign Office to warn them about this supposed imminent attack in Beirut.

Once Sir Gyles was informed of the concerns from the minister’s office in London he wrote back on July 21, 1946, in an unusually forthright manner saying he could see that senior figures suddenly were talking about this threat, but: “Owing to complete lack of information here we cannot advise him.”

Terence Shone, the British Minister for Syria and Lebanon, had already told London from Beirut a day earlier that security had been increased, and he didn’t see the utility of any further precautions.

But Philby had already stirred up significant interest at a senior level in London, so Sir Gyles and Arthur Giles, the outstanding intelligence officer who ran the Palestinian police force’s Criminal Investigation Department, were both dispatched to Beirut.

As a result, they both missed the attack attack on the King David, which took place during the postwar period when the two terror groups—the Irgun and Lehi—had begun working alongside the Haganah, the military wing of the Jewish Agency, which was effectively Israel’s government in-waiting.

The bombing was widely condemned by the Jewish community in Palestine, as well as by leaders worldwide. The Irgun—which carried out the attack under the command of future Prime Minister Menachem Begin—blamed the British for failing to evacuate the hotel after they had been sent a warning. British officials have always denied that any warning was ever received.

The aftermath of the attack—which hardened the position of U.S. President Harry Truman against the Zionist extremists—saw plenty of internal recriminations, especially at the Jewish Agency, whose leaders were appalled by the scale of the bloodshed and furious to discover that it had been signed off by the then-head of the Haganah’s national staff—Moshe Sneh.

Although they would not have been able to foil the attack, Sir Gyles felt that he and the missing law enforcement chief were not in place to properly lead the investigation into the atrocity. As he wrote all those years later: “I could not help feeling that the Foreign Office report was somehow inspired by Begin.”

Begin was often celebrated as having outsmarted the British in Palestine—using a relatively tiny guerilla army of a few thousand men to force out the colonial giants—but there is very little evidence of him employing disinformation campaigns to wrong-foot the British authorities.

Reached at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center—“the state-sponsored project to preserve and propagate the legacy” of the former Irgun leader in Jerusalem, Yisrael Medad said he had never encountered any such strategy. “As far as I know, and I think I’ve read almost everything, nothing like that specific instance [of disinformation] ever happened,” he told The Daily Beast.

Long before he became Prime Minister of Israel, Menachem Begin was involved in the struggle against British control. (David Rubinger/Getty)

Hoffman believes Sir Gyles’s theory of interference was made on “justifiable grounds” even if the origin of those intelligence reports from Beirut will remain a mystery.

“We don’t know if this was an Irgun disinformation,” he said. “But I think Philby’s seizing upon it plays into his wider strategy of distracting the British in Palestine.”

The newly revealed Philby memo dated more than two months before the King David Hotel bombing, on May 5, 1946, and declassified by the British government in September last year, suggests a clear pattern.

“Emphasizing [the fake Beirut plot in July] becomes important if there is a goal of deception and distraction which I think there would have been,” Hoffman said. “I think Philby saw it as yet another opportunity to distract the British.”

The previously unpublished memo shows Philby disseminating a spurious report that suggested a French officer would parachute into Palestinian territory to try and sell weapons to the Zionist terrorists.

The original dispatch from MI5’s Major James Robertson sent to Trafford Smith on April 30, 1946, claimed that Zionist agents had met with a French representative in Beirut and discussed a plan whereby the French “drop an officer by parachute into Palestine in order to discuss the sale of arms to the terrorist organizations.”

Naturally, there is no evidence that the French ever dropped such a sitting duck into Palestine.

Some French officials and military figures were indeed sympathetic to the Zionist cause and provided expertise or even weaponry, but there is no reason and no way they would have arranged a rendezvous with terror groups plotting against their allies, the British, on British-controlled territory.

Nonetheless, Philby pulled the intelligence report and had “this interesting information” shared across the agencies in London and the offices that were attempting to deal with Zionist guerillas, including Jerusalem, Beirut, Paris, and the Mideast.

At his desk in the heart of Britain’s clandestine world of intelligence in Whitehall, Philby received thousands of reports of varying veracity from all over the world. This one he seized upon.

This was “typical Philby” said Professor Andrew, who summed up the mole’s anti-British motivations in the official history of MI5, Defend the Realm: “Kim Philby, like his masters in Soviet intelligence, secretly welcomed the terrorist campaign against the British mandate in Palestine as a blow to British imperialism in the Middle East inflicted by ‘progressive’ Jews of Russian and Polish origin.”

Kim Philby believed that his upper class background protected him from the suspicions of his colleagues. (Laski Diffusion)

MI5 and MI6 historians agree that Philby often interfered to wreck his British colleagues’ intelligence operations.

“He was doing his best to try to manipulate British investigations into Soviet agents, so spreading disinformation in that way,” Calder Walton said. “Often, it’s just spinning wheels, anything that can assist Soviet intelligence and obfuscate British intelligence would be his marching orders.”

He wasn’t simply a double-agent working for the British and then telling Moscow what he and his colleagues knew; he was actively working against British operations himself.

Or, to put that in Philby’s own words: “All through my career, I have been a straight penetration agent working in the Soviet interest.”

“Given Philby’s unnatural interest in Palestine—there's no explanation why he would be so concerned about Palestine—I think you can say that it was very useful to divert and distract British attention, but also weaken the British military or at least have them doing things in Palestine that prevented them from working against Communism,” said Hoffman.

“If British intelligence are concerned with hunting down French or Irgun, or Lehi emissaries around the Middle East they have less time to pay attention to Soviet penetration and Soviet activity, they have less manpower.”

What we will never know is the true motivation of Kim Philby. Was he toying with Britain’s battle against the Zionist militants under orders from Moscow? Had he developed this strategy for helping Mother Russia on his own? Or was he throwing his colleagues off the scent for some deeper reason now impossible to discern—or simply for sport?

Whatever inspired his actions, it is now obvious that MI6 efforts to keep control of British territory in Palestine were being undermined by a Soviet agent within.

—with additional reporting by Christopher Dickey