MEXICO CITY—On Monday afternoon, award-winning Mexican journalist and author Javier Valdez was pulled from his vehicle and gunned down mercilessly just moments after leaving his office in Culiacán, Sinaloa.He was shot at least 12 times—his corpse left sprawled on the pavement in the middle of the afternoon, mere blocks from the news organization, Ríodoce, that he founded. His car was left abandoned with the engine still running.

“Javier was quite fearless but he was also very cautious,” said Committee to Protect Journalists correspondent Jan Albert Hootsen, who travelled to Culiacan on Tuesday to attend the journalist’s wake and funeral. “I used to always visit him when travelling through Sinaloa—it’s a relationship that goes back about seven years.”

While recounting the “very angry and emotional protests of journalists in Culiacán, demanding answers from the governor and justice for Javier” in a telephone interview on Wednesday, Hootsen said his friend was “universally loved and respected by the people there, and known for being independent, truthful, and also a tremendously gifted writer.”

ADVERTISEMENT

He said, local members of the media demanded answers from Sinaloa Governor Quirino Ordaz Coppel—“How could this have happened? How is it possible that one of Mexico’s most beloved and well-known journalists could be killed?”

“There is so much anger and sadness, and questions of whether one can even continue working in a place like Sinaloa where safety may not be guaranteed,” said Hootsen, speaking from the state which birthed one of Mexico’s most prominent drug trafficking organizations—the Sinaloa cartel, formerly led by infamous and now-jailed drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

News of the murder of one of Mexico’s most prominent journalists, who said that “being a journalist in Mexico is like being on a blacklist,” quickly reverberated across Mexico. Valdez, after all, is just one of six journalists killed in Mexico in less than three months.

His murder comes mere weeks after the assassination of Cecilio Pineda in Guerrero, Maximiliano Rodríguez in Baja California, Miroslava Breach in Chihuahua, Filiberto Alvarez in Morelos, and Ricardo Monlui in Veracruz.

They join the dark list of at least 11 journalists murdered last year, whose deaths made 2016 the most violent year for Mexican journalists since 2006—the official start of the brutal, militarized drug war in Mexico.

So far, not a single person has been arrested over the recent murders. But this staggering impunity is nothing new. In fact, of the more than 125 journalists whose deaths have been officially recognized in Mexico since 2000, less than three percent have resulted in arrests.

On Tuesday, in an unprecedented show of solidarity, dozens of news organizations protested the unpunished killings by blacking out their sites or choosing to take the day to publish only stories about Valdez and the unimpeded murder of their colleagues.

Using hashtags like #NosEstánMatando (They Are Killing Us), and a phrase often used by Valdez, #NoAlSilencio (No To Silence), journalists across Mexico lamented the murders with a slew of articles, social media posts, and in protests in the streets.

Using the hashtag #UnDíaSinPeriodismo (A Day Without Journalism), local and national media companies across Mexico banded together to say that they would take the day off altogether or only post content related to the murders. Though seemingly a contradiction of what Valdez preached, the silence that resulted was loudly and resoundingly heard in Mexico.

For the sake of full disclosure, I must confess to being more than a passive observer in this one. I started the #UnDíaSinPeriodismo hashtag at 4:30 p.m. local time on Monday, and went on a tweeting spree until it stuck. (In Mexico, we are all disgusted by the lack of official protection afforded journalists who risk their lives to keep the public informed.)

“Maybe the presses should come to a grinding halt?,” I tweeted, using the hashtag. “What would a day without journalism look like? Would anyone notice? Would the international pressure spark genuine action from an inept government?”

It began trending on Monday evening and stayed among the top trends in Mexico for more than 24 hours. By mid-day on Tuesday, the hashtag had been used more than 20,000 times.

The first media company to announce the blackout was Animal Político, perhaps Mexico’s most trusted source of independent journalism. Soon, many others like Tercera Vía, El Siglo de Durango, and Letras Libres joined in. By Tuesday, the day of the self-imposed blackout, international media companies like Vice News in Mexico, and the Spanish-language versions of Fusion Media, Al Jazeera and Huffington Post had also joined in solidarity with their colleagues in Mexico. Many more news outlets—at least three dozen—participated in the day of mourning, and joined the silent protest that echoed across Mexico. Press freedom organizations and human rights defenders, like Amnesty International and the Committee to Protect Journalists, also used it to show support.

“You can’t kill the truth by killing journalists,” Animal Político tweeted on Monday afternoon, while announcing the blackout. “Killing a journalist is confirmation that [in Mexico] there is no free speech—that the right of every Mexican to know what happens in this country is cancelled.”

“In Mexico, journalists are killed because they can be, because nothing happens,” said Daniel Moreno, the head of Animal Político. Moreno said he’d never seen so much solidarity, and called the self-imposed blackout “unprecedented.”

On Tuesday evening, some of Mexico’s most prominent journalists and their allies protested and spoke in front of the Interior Ministry in Mexico City: like Carmen Aristegui, Denise Dresser, Temoris Grecko, and even actor Diego Luna, who said it is “indispensable that journalists know we are with them.”

“Citizens deserve a free press,” he said. “What just happened, should have been enough to collapse the whole country. The day that we all come out [in protest] is the day that we will be heard.”

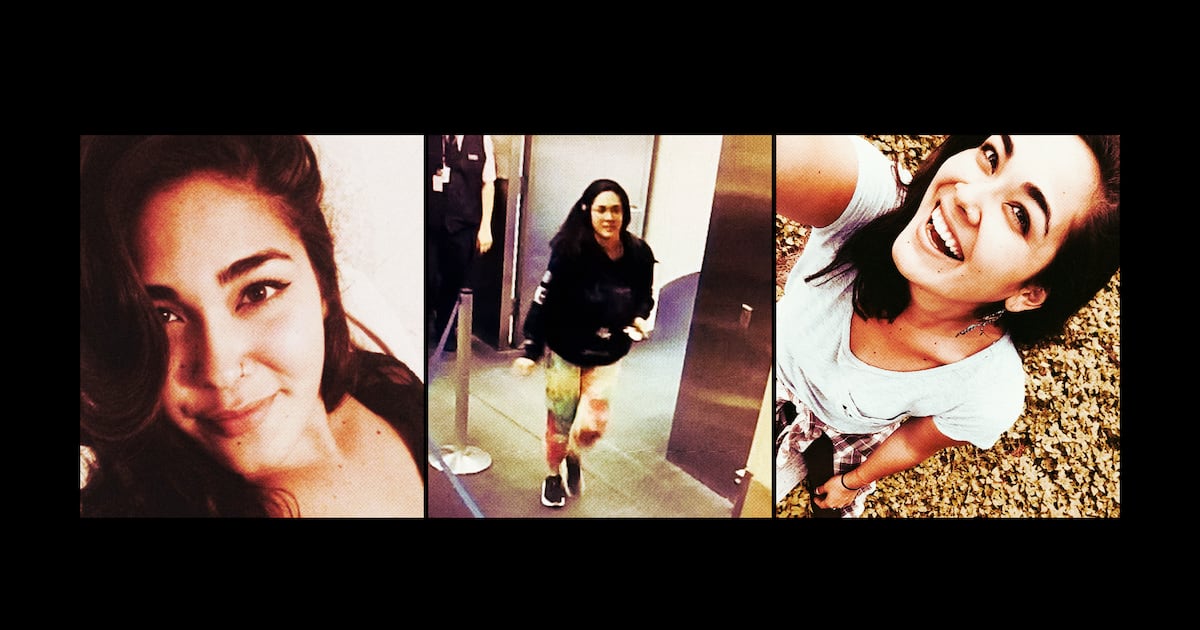

Journalists wore black and lit candles and torches for their fallen colleagues, silently watching the faces of their recently murdered friends and co-workers projected on the side of the government building above an enormous blackened Mexican flag hung by protesters.

Renowned author and journalist Lydia Cacho read an excerpt from Valdez’s latest book Narcoperiodismo, or Narco-Journalism: “Why the hell should I go out to face the fucking fear? To see the bodies on the highways, hands tied, with a bullet to the head? Why report the protests if those at the top ordered the police and grenadiers to go after the photographers and journalists? ”Colleagues, at times, chanted—“Justicia! Justicia! Justicia!”—and a sea of cameras documented their words. Javier Valdez, who before his death tweeted “Miroslava [Breach] was killed for having a big mouth. Let them kill us all, if that is the death sentence for reporting on this hell,” will be sorely missed in Mexico.

The murder of the 50-year-old recipient of the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2011 International Press Freedom Award, and author of several books including Miss Narco—a book about women caught up in the seedy underbelly of organized crime in Mexico—resonated across Mexico like none other in recent memory. Both national and foreign correspondents lamented his death and expressed solidarity with those reporting from some of the most scarred and embattled regions of Mexico—now one of the world’s most deadly countries for reporters. “There are a great many brave journalists in Mexico who are constantly fighting to make their jobs safer,” said my friend and fellow foreigner Jan Albert Hootsen from Culiacán. “Foreign correspondents, as a rule, are rarely specifically targeted or persecuted in Mexico. Our situation doesn’t remotely compare to that of journalists in Mexico, specifically those working at a local level.”

“For everyone here, and the countless foreign journalists [Valdez] has helped, his death is an enormous shock,” Hootsen said. “This was a very sad and emotional day for all of us.”