Shortly after Donald Trump won the presidential election last November, reports surfaced that he was considering extending an offer to Dr. Ben Carson—the former neurosurgeon-turned-rival—to serve in his forthcoming administration as secretary of Health and Human Services. As it turned out, there was no offer. And in disputing this speculation, Carson’s business manager Armstrong Williams said that, even if there was, it wouldn’t be accepted, because “Dr. Carson feels he has no government experience, he’s never run a federal agency. The last thing he would want to do was take a position that could cripple the presidency.”

Which naturally raises the question: If Dr. Carson believed himself too inexperienced for federal employment, what was he doing running for president in the first place?

PACmen sheds considerable light on that conundrum, by focusing on the two organizations determined to get him elected to the nation’s highest office. Premiering at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival this week, writer/director Luke Walker’s non-fiction film is a behind-the-scenes peek at the inner workings of Super PACs—which, for those not in the know, are independent political committees (allowed under law by a January 2010 U.S. Supreme Court Decision) that, so long as they don’t directly coordinate with a political campaign or party, can raise and spend as much money as they like, from whomever they like, on behalf of a candidate. They’re the financial muscle behind today’s men and women running for office, providing the economic and logistical support necessary to turn contenders into winners.

Except, of course, that in this case, Dr. Ben Carson was not a winner, despite the best efforts of the two Super PACs trying to stick him in the White House: 2016 Committee (aka “Run Ben Run”) and Extraordinary America. These organizations agreed to work in tandem for Carson, and Walker was granted considerable access to both of them as they endeavored to first get the word out about their candidate, and then to fight mounting media criticism about the viability of their man, and their cause. The result is a documentary portrait of the country’s horrifying 21st century political reality—one that’s rife with money men enlisting, and conning, true believers into backing would-be politicians who are unfit for the job in just about every respect.

“The world is going to hell in a hand basket, and it’s up to us to stop it,” says 2016 Committee mastermind Philip Souza IV during one of the many moments throughout PACmen in which Super PAC members predict an impending doomsday unless Carson—a man wrapping himself in religiosity, and running on the basis of his inspiring personal rise from poverty to neurosurgeon prominence—is inaugurated. As Extraordinary America chairman Jeff D. Reeter mans teleconference calls with his staff to see how they can best improve Carson’s odds in Iowa, South Carolina, and beyond, Souza rallies his troops by asking them to imagine how good it’s going to feel when Carson wins, and they can all sit back and know, “We put him there.” Even Carson himself initially drinks his own Kool-Aid, telling Extraordinary America acolytes by phone, “I believe that this is God’s will. Absolutely I think we can win… I think there’s very little chance that we’re going to lose.”

As PACmen elucidates, these Super PACs chose Carson as their savior largely on the basis of both a National Prayer Breakfast speech that saw him criticizing President Obama to his face, and his stirring backstory, which—as immortalized in the cornball Cuba Gooding Jr. made-for-TV movie Gifted Hands—was highlighted by his teenage embrace of Jesus Christ after angrily trying to stab a man to death, the knife miraculously breaking on the victim’s belt buckle. Even Trump, at a rally, responded to that yarn by asking: “How stupid are the people of the country to believe this crap?” While Trump’s own subsequent election suggests a depressing answer to that rhetorical query, when it came to Carson, no one was fooled. Before long, media outlets were shredding his biographical tall tales—an enormous problem, given that he really had nothing else to sell.

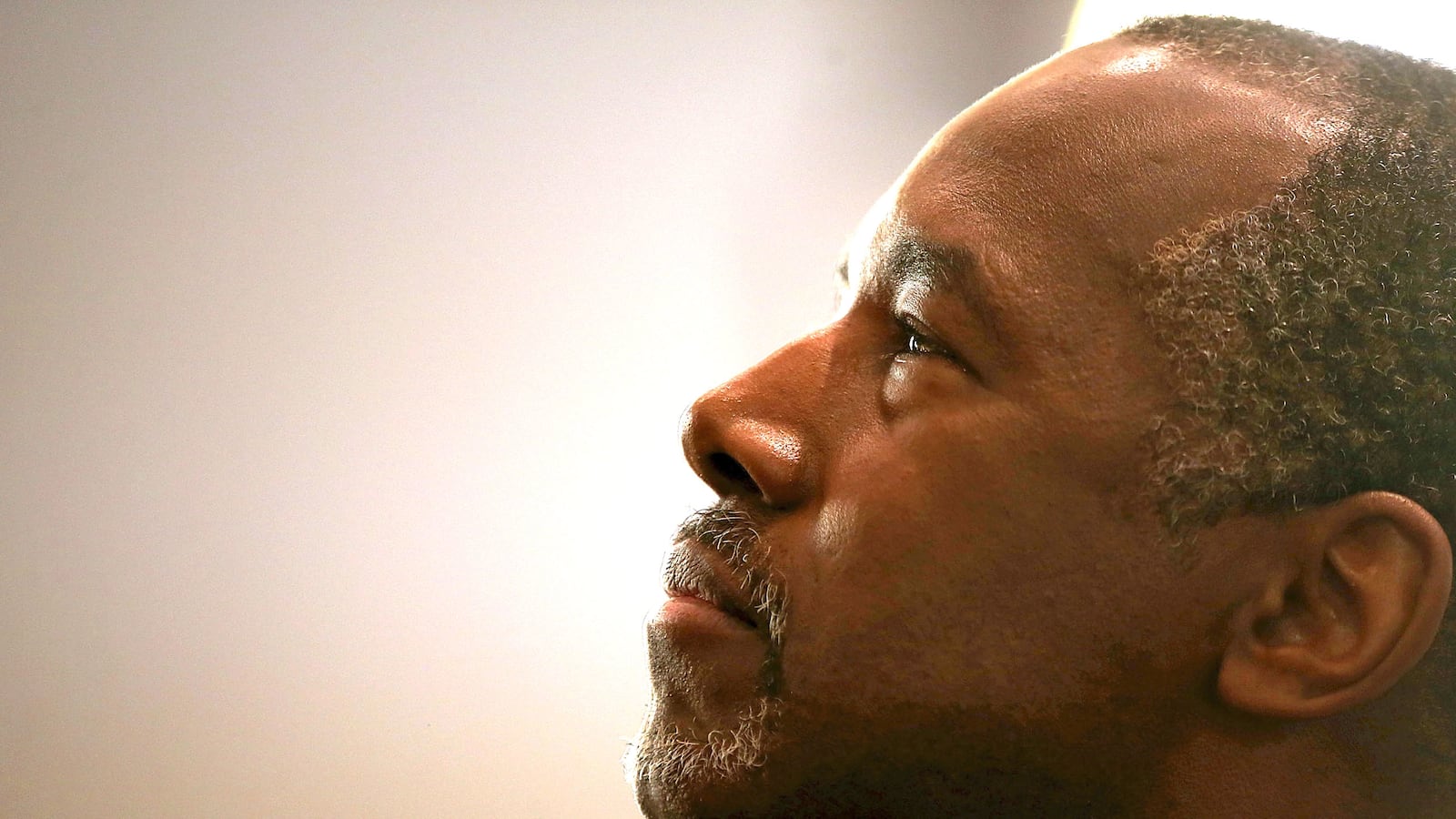

What’s revealed, first and foremost, by PACmen is the wholesale emptiness of Ben Carson the candidate, a man with scant knowledge about policy or the political process. He comes across as a genial, sleepy speaker prone to platitudes and awkward turns of phrase, and his dire warnings of impending catastrophe lest “we the people” rise up to alter humanity’s course are of a stock, generalized sort. Even when reading a script, he barely seems to comprehend what he’s saying, as in his infamous mispronunciation of Hamas—the Palestinian terrorist organization—as “hummus” (a gaffe mocked by Stephen Colbert, among others). Even without direct access to Carson, Walker’s film solidifies the impression that he was out of his depth and thus, that his crash-and-burn in the primaries was an inevitability.

More eye-opening, however, is the shameless amorality of the Super PACs, which are funded by men (such as Extraordinary America founder Terry Giles) who are brazen about their desire to maintain their own wealth and power—no matter the ethical compromises it might entail—and populated by delusional activists convinced that praying hard enough (via prayer lines) will somehow bring about their preferred outcome. That the former are exploiting the latter to keep themselves rich is difficult to miss in PACmen. Yet the final lesson imparted by Walker’s film is less about the haves using the have-nots for their own personal ends, and more about the way in which our current political system is being hijacked by wealthy donors and their third-party groups, which seek to install puppets who, owing their fortunes to these Super PACs, are then beholden to their will.

It may not have completely worked in the case of Carson (although his current role as U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development says something about its effectiveness). But as PACmen makes clear: He’s merely the start of a truly terrifying new world order.