A few months have passed without a peep from the feds, so it’s probably OK to talk about what happened down on the border on April 1:

A silver Dodge Caravan rolled through the hot South Texas plains. The last Border Patrol agents had drifted way, and the four men in the Caravan were feeling pretty good. True, Ron, the driver, had a puddle of sweat on his forehead. But that’s because, as one of the men puts it, “Ron is a white boy.” The van pulled within six feet of the border wall. Ron and his team slipped out. Their work took less than two minutes. Then they were driving north again, with a studied nonchalance that stopped just short of looking at the sky and whistling. Someone muttered, “Mission accomplished.”

Ron and his men aren’t gunrunners. They’re artists. They’d left a piece of art on the border wall. Politicians have called America’s 600-mile fence a snub to a friendly neighbor or a necessary roadblock against north-bound immigrants. Ron English, the New York street artist, sees it as a canvas. “It was a virgin wall,” English says proudly.English, who is 52 years old, is like Banksy without the camera-shyness. A large man with white hair glaciating down the sides of his head, English invites me to his Beacon, New York, home to explain the details of the caper. The usual target of English’s art is a billboard. He seeks out a billboard with a corporate icon—Ronald McDonald, say—scales the thing, and replaces the image with one of his own wicked devising. Some people call this “culture jamming”; English calls it “billboard liberation.” After the English treatment, Ronald McDonald becomes a fatso. Joe Camel lies in state in a coffin. Apple’s “Think Different” campaign, which enlists poor Albert Einstein as a computer salesman, acquires a new face: Charles Manson.English began liberating billboards in the 1980s in Dallas, where, to hear him tell it, he was defending the populace from “corporate ballyhoo.” English is a relentless corporate noodge; he has been called the “Robin Hood of Madison Avenue.” But since those early billboards, English’s work has gotten so skillful, so deliciously on the mark, that he has reached cultural jamming’s endpoint. These days, his billboards don’t lift from Madison Avenue as much as upstage it. English’s “Abraham Obama” poster became a totem of Obama’s 2008 campaign, while his John McCain spoof was arguably McCain’s most professional-looking ad.

English paints border walls, too. Back in 1986, he painted a sweeping mural on the Berlin Wall. In 2007, at Banksy’s invitation, English hung posters on Israel’s West Bank wall, working under the gaze of Israeli guards with rifles. "I wasn't that concerned with being shot," English tells me.

What’s with the wall-painting? “Nobody has any concept of a wall,” English says. “But if we go paint on it, then all these people will come photograph it.” The border wall, like a Mickey D’s ad, can no longer sit sedentary in the back of the American mind. Once the wall is jammed, it loses some of its metaphorical fearsomeness. You might even begin to wonder why the wall exists at all. After he’d conquered Berlin and Bethlehem, English’s friends asked him, “Why don’t you go paint your wall?”

The heretofore secret South Texas border-wall team can now be named: English; his assistant Beau Stanton; the Austin-based artist Antonio Reyna III; and Joseph Bravo, the executive director of the International Museum of Art & Science in McAllen. “We did it,” says Bravo, “so we as might as well confess to it.” Brian Wedgworth, a South Texas artist and sculptor, says he acted as a lookout down the road.

An English team comes together haphazardly. For instance, Antonio Reyna met English in a McAllen bar the night before the caper and somehow wound up in the van the next day. To run with English, you can’t mind being arrested. (English has been arrested several times.) Indeed, as the silver Dodge Caravan made its way to the border, Bravo, the museum director, announced he had pre-arranged his bail money. This was the moment Reyna began to envision himself being thrown into a hole by Homeland Security officials. “The whole time I’m thinking, Why are we here?” Reyna says. “For the sake of art, I guess.”

Reyna led the men to a section of the border wall between La Joya and Penitas, Texas, two specks on the map with a few thousand residents. This wasn’t the San Diego fence that pols like to pose in front of, or even the El Paso boundary, where a 15-year-old was shot by the Border Patrol last summer. This was a forgotten realm of America. “All the buildings on the north side of the wall are boarded up,” Bravo says. “All the businesses are boarded up. It was cryptic. There was something toxic. Life had existed, and then the wall happened. Now, everything was dying.”

The four men got out of the van. Earlier they’d seen Border Patrol SUVs parked like predators in the tall grass, and they knew they’d be back. “Our window was less than two minutes,” Reyna says. The South Texas wind was blowing so hard that Reyna and Bravo had to hold the flapping poster facedown on the ground, while English slathered the thing with wheat paste. Bravo caught a glop of paste right in the eye.

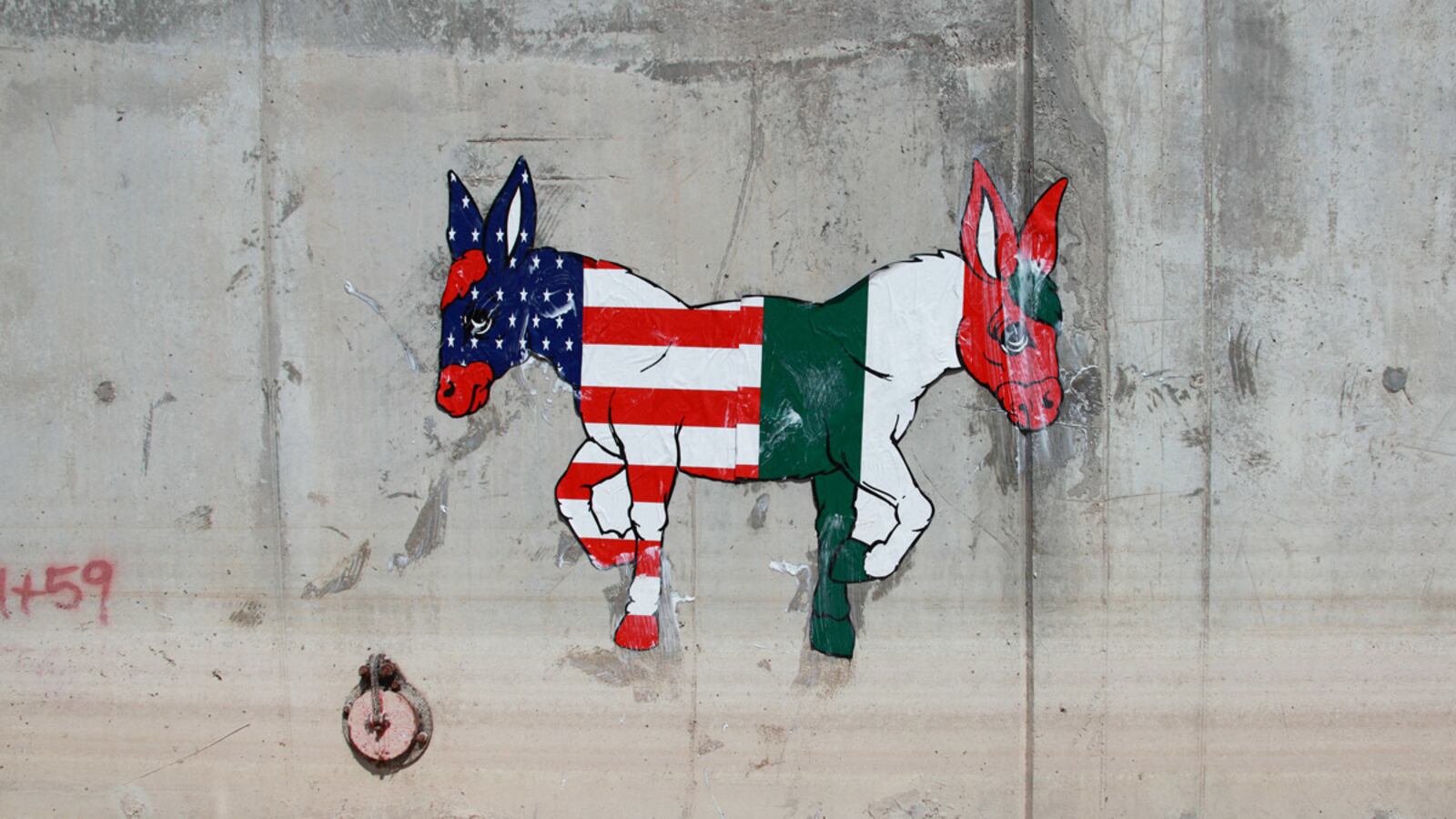

The poster was typical English. It featured a two-headed donkey, one donkey head decorated with a U.S. flag and the other with a Mexican flag. If the men had paused to consider English’s message, they might have thought the United States and Mexico are linked by historical destiny, but that mulish policies on both sides had created the current madness. But nobody had time to think of that. They slapped the poster on the border wall, took a photo, and hopped back in the van. On the road, they passed Border Patrol agents cruising toward the spot they’d just vacated. Later, the men celebrated by drinking Dr Pepper.

English’s team also crossed the border into Reynosa, Mexico, where they unveiled another piece of art. It was a cardboard Uncle Sam, designed to look like the signs you see next to roller coasters telling you the minimum height. The sign read, “You must be this color to enter this country.” A photo of that piece wound up on Boing Boing.

So: Can we consider the border wall jammed? Stanton: “As far as execution, it could not have gone better.” Bravo: “It was wonderful. Tremendous impact. It put wind in everybody’s sails in the art world down here. It’s a little anticlimactic that it’s over.” Reyna: “Ron did shake it up a little. He added fuel to the fire. He was the rock in a pond and the waves are still going, you know?”

A week after the caper, Brian Wedgworth, the lookout, went back to the border wall. He found English’s donkey poster had been mauled. Someone had torn off the Mexican half, leaving the metaphorical “America,” here at its most extreme point, cut off and alone. Now that was an artistic statement! Joseph Bravo says, “At which point I thought, Everybody’s a curator.”