YANGON, Myanmar — When she talks about imprisoned Rohingya Muslims, her people, her pretty face changes; her eyes darken, her straight-backed posture grows tense, and her voice grows louder: “The government now deny that we even exist,” she says.

A walking symbol for discriminated minorities, Wai Wai Nu believes that the only way to convince her country’s newly elected government to include all ethnic minorities in the democratic process is by mobilizing, and pushing.

She says she is ready to turn into a monk for that, to live without any personal life, devoting herself only to one goal: to end the disaster for one of the most discriminated-against groups on the planet, to win freedom for more than 200,000 internally displaced people living in ghettos and camps surrounded by police checkpoints in Rakhine state.

Nationalism, inequality, injustice rolled over the young woman’s own life, like a tank. Burma’s military regime believed that Wai Wai did not deserve freedom because she was the child of a Rohingya politician. For that one crime only, she spent her youth from 18 to 25 in notorious Insein Prison in Rangoon (now Yangon, Myanmar).

When a Rangoon court sentenced her father, former elected member of Parliament Kyaw Minm, to 47 years in prison, Wai Wai was a first-year student at a law school. Two months later, she, her mother, her sister, and brother were each convicted to 17 years in prison. “I could tolerate the food, all the prison conditions that we lived in, except for the fact that I could not continue my education,” Wai Wai told The Daily Beast.

At least she was not alone; she talked with other incarcerated teenage girls. Some of her prison mates, despairing and hopeless, turned to drugs and prostitution. That was when Wai Wai decided to become a women’s rights defender and mobilize the women of Myanmar to a fight for justice.

After eight years in prison, Wai Wai Nu and her Women’s Peace Network Arakan had trained more than 500 students, mostly women, to understand the true meaning of words like “justice” and “human rights.”

When Wai Wai and her father visited an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp for Rohingya a few months ago, she saw thousands of teenagers living without hope. She told them what she was able to do when she got free, and to have strong hopes for the time of freedom coming for them.

Today some of Wai Wai’s friends on Facebook call her their Rohingya Princess. She did not like the nickname. Strict as a soldier at war, deeply devoted to her struggle, she shook her head: “I am not a princess, I do not know how to free minorities right now, but I know one thing: that is my dream, I want to be a good human being and bring people justice.”

In prison, Wai Wai admired two politicians, the most famous Burmese woman, Aung San Suu Kyi, also a political dissident, who was living under home arrest in Rangoon at the time, and the American politician, then a senator, Barack Obama.

“I thought, if Obama wins the elections, he will change not only the United States, he would change the entire world,” Wai Wai remembered. Last year the young Myanmar dissident had a chance to have dinner with the American president at the White House and personally give a push to the U.S. in Myanmar.

Wai Wai smiled at the memory: “I was the only foreigner at the table, the other eight young people were American; it was totally cool, when instead of letting me introduce myself, the president told everybody my story,” Wai Wai said, but then frowned: “I might have disappointed the president by saying that his policy toward Burma is not a success story, for as long as we see the continuation of human rights violations throughout the country, especially the atrocities in Rakhine state,” Wai Wai said.

From early morning to late at night, seven days a week, Wai Wai Nu works on pulling together divisions of young activists, relying especially on the strength and courage of young women like her.

One recent Saturday began at 9 a.m., teaching English to a group of 10 students at her office. Blackouts, which happen in Rangoon every few hours, did not stop the class. In Burma, where an average family of five members live on $200 a month, blackouts are not the worst hardship.

“My life changed, when I met Wai Wai Nu and came to her training classes,” says 18-year-old Pyae Sone Soe. “She became my sister and teacher, my inspiration; she taught me about my citizen’s rights.”

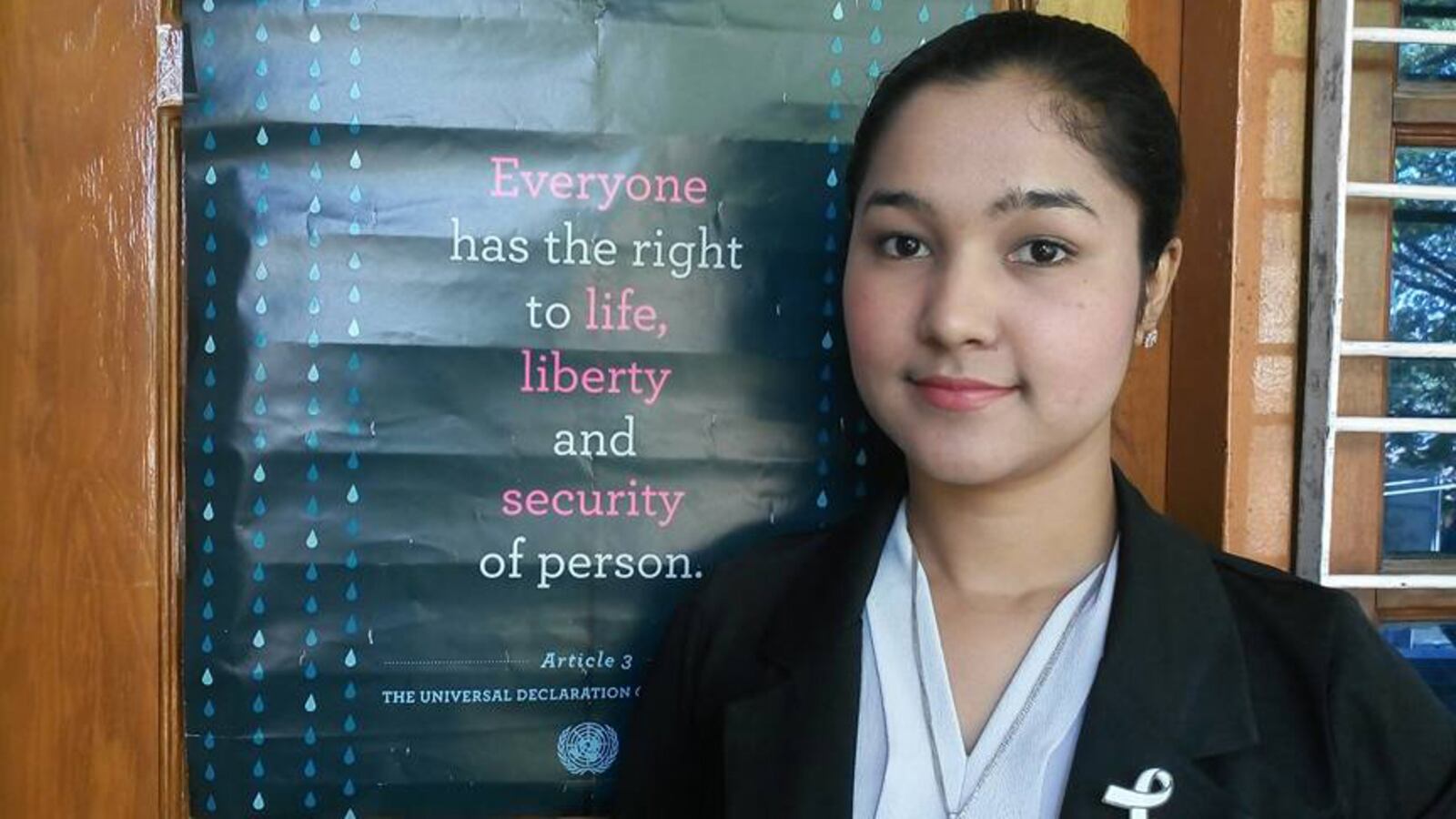

After Wai Wai’s morning lectures, she rushed to a panel discussion for Rohingya activists, and at 11 a.m. Wai Wai, dressed in a black jacket and a longyi, a traditional long skirt, was speaking into a microphone at a long conference table.

“We should not be satisfied,” she said. “We should involve more women in the peace process, demand that the government fulfill their international obligations, create mechanisms to stop violations against women, come up with a plan to have up to 30 percent of women on state positions.”

The next speaker at this conference on Developing Strategies for Advancing Women’s Rights in Myanmar was another beautiful and thoughtful leader, 24-year-old Thinzar Shunn Lei Yee, who stressed the need for legal and administrative reforms.

As with many young female activists in today’s Myanmar, Thinsar and Wai Way both wanted to be as courageous and strong as Aung San Suu Kyi, and maybe one day come to replace her. “Myanmar’s women, civic and human rights defenders, are mobilizing in a powerful movement,” says David Mathieson, the senior researcher on Myanmar in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch. “Wai Wai is one of the brightest of them. She could definitely be a brilliant politician.”

The Rohingya Muslim minority has experienced years of discrimination by Burmese nationalists. At least 140,000 of them were forced into temporary camps in 2012, when a violent ethnic conflict broke out between Muslims and the Buddhist majority in the state of Rakhine.

“It would not be accurate to say that Rohingya IDPs live in a concentration camp, but it is true that they cannot walk out and freely go to a hospital, for instance; for serious medical help they would need official escort,” Mathieson explained.

Wai Wai realized that her role model, 70-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi, the woman now in power, had a burden of reforms, ethnic conflicts, a legacy of military rule, a crisis in IDP camps, and other grave problems to deal with. But she still believed that the leader of the new government would do more and sooner for the Rohingya.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that Wai Wai has met Obama, but not her other hero. If only Wai Wai could one day meet with Aung San Suu Kyi, she knows what she would say: “I think I would tell her that her vision for our country turning democratic will only be a success when everyone has a chance to participate in the process, everyone should have opportunity to have access to the process,” Wai Wai told The Daily Beast. “Rohingya should have equal rights, too—she might already know this, but I would like to remind her.”