The body of a young girl permanently occupies a hospital bed in a rental apartment in New Jersey. The letters of her name, pink and surrounded by paper butterflies, hang above her head; inspirational quotes and Bible verses are mounted on pastel-colored paper and stuck to the wall. A striped blanket hides the medical technologies that keep her in this world: There is a feeding tube surgically inserted through a hole in her stomach. There is a ventilator tube inserted through a tracheotomy in her throat.

Her mother and a 24-hour nursing staff change her diapers and turn her body from side to side to prevent her skin from developing dangerous bed sores. She cannot eat, open her eyes, speak, or leave her bed. New Jersey is the only state in the country in which this girl is not dead.

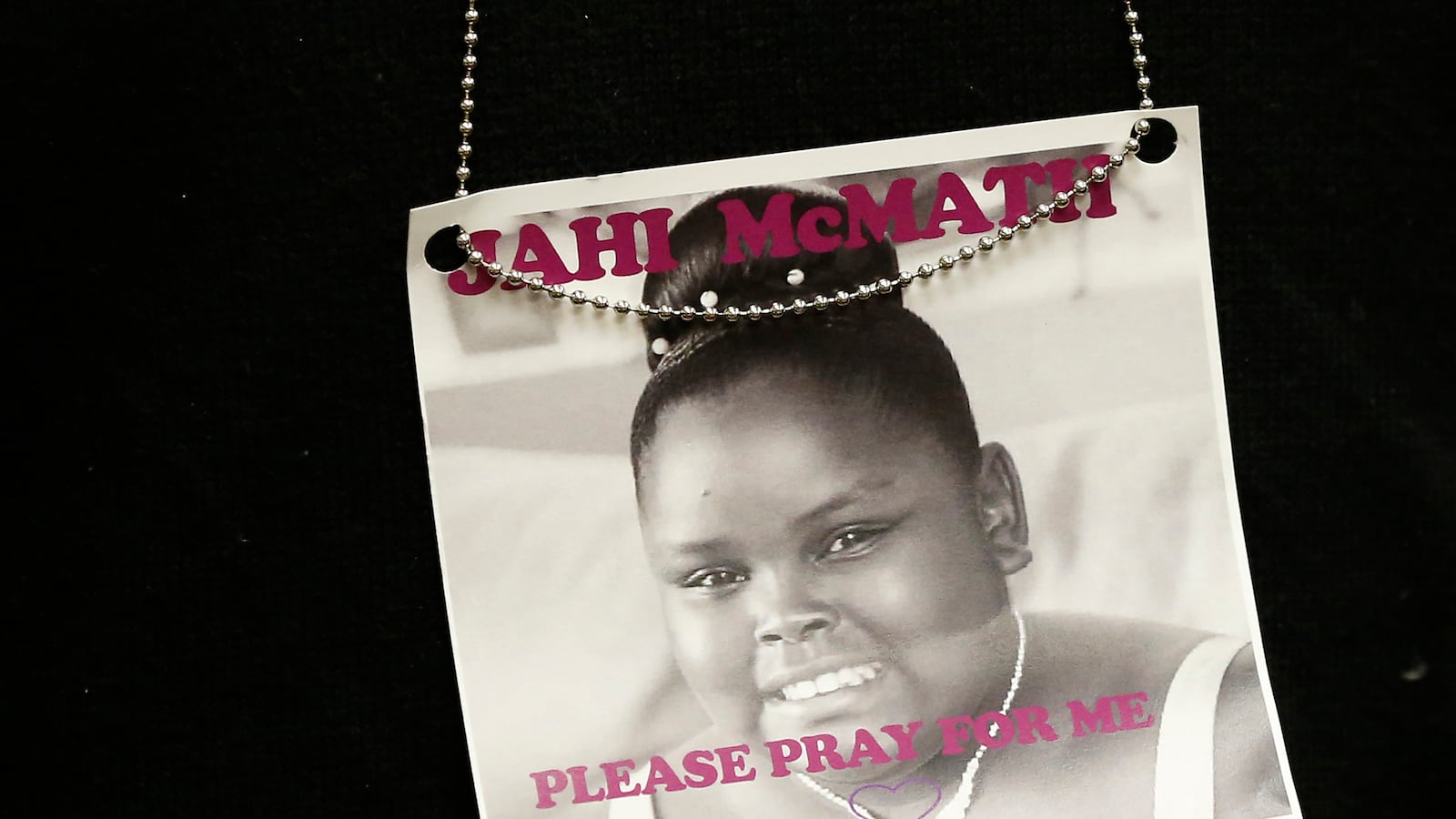

Her name is Jahi McMath and just over two years ago, after an extensive tonsillectomy, she began to hemorrhage blood and became unconscious. Doctors in her home state of California ultimately issued her a death certificate. Jahi is in New Jersey because her family refuses to accept the doctors’ assessment that she is dead. Or to be specific, because it is the specifics that are now at issue in multiple court cases at the state and federal level: Jahi McMath is, according to every doctor (not employed by her parents or lawyer) who has examined her, brain dead.

Jahi’s mother, Nailah Winkfield, says she is waiting for God to intervene. She has told the press that Jahi is improving. On Jahi’s birthday last October, the family posted on their Facebook page:

Thank you Heavenly Father for the Gift of Life, the Life You granted Jahi, a Life she so much deserves and desires to live faithfully for You through the next year and many many more years to come. Happy Birthday Beautiful Jahi, You Are 15 today, your friends love you, your family love you, many many people worldwide love you, but most importantly God loves you. May you, Jahi McMath receive the gift of continued healing and full recovery. May God protect and keep you safe, showering you and your loved ones with strength, love, health of mind, body, soul and more blessings in abundance. Keep Winning, Love you always, #TeamJahi.

In all 50 states, brain dead is dead. Brain cells have never been shown to come back to life once dead. But in New Jersey, state law permits those who do not agree—those very few who have religious convictions that the heart is still the sole indicator of death, even if that heart is artificially supported—to keep their loved ones on physiological support. Some family members are willing to huddle in daily prayer for as long as a miracle takes. In this new formulation of “natural death,” the sustenance of machines becomes natural.

The difference between alive and dead may seem quite clear, yet the definition of death has changed over the past several decades because of medical advances. Death once meant the almost simultaneous cessation of heart rate, breathing, and brain function. The advent in the late 1960s and early ’70s of defibrillators and respirators, able to keep the heart and lungs functioning indefinitely, shifted the definition of death to the brain and its mysterious, complicated activities.

To address those resulting ethical questions and establish a public policy consensus, a presidential commission in 1981 concluded that “humans shall be pronounced dead when all brain functions are lost irreversibly, even if the heart and respiratory function continue.”

But problems with the commission’s statement persist. Many find that the requirement that every part of the brain be irreversibly dead for death to be pronounced ignores the fact that ancillary parts of the brain are still active after a person has ceased to exist. Other parts of the brain may survive and be detected by scans, hormonal regulations may continue despite the death of other parts of the brain. Are these “residual functions” really signs of life? And what then, is the difference between biological life and sentient life? Where in your brain do you exist? And what makes you alive? Are you alive if you grow? If you menstruate? If you recognize your mother? If you can open your eyes? Or yawn? Others have contested the very term “brain death” because it creates confusion, as though brain death is a stage and not the end. Call it what it is, they say: death.

Controversies—and all too sadly, multimedia extravaganzas—have surrounded other types of brain damage, like the medical and court cases of Karen Ann Quinlan (New Jersey, 1976), Nancy Cruzan (Missouri, 1990), and Terri Schiavo (Florida, 2005). But these women were all diagnosed with persistent vegetative state, meaning their brain stem, at least, still exhibited activity. Yet their cases all concerned removal of physiological support.

In every instance, the primary opponents of removal were Catholic leaders, whose position was later articulated by Pope John Paul II, and their “pro-life” allies, who had built at least part of their political platform on opposition to women’s medical privacy.

Terri Schiavo’s legacy can still be felt. She had been kept on a feeding tube for more than 15 years as her husband, Michael, and her family, the Schindlers, contested her status and health in the courts. Finally, a Florida judge ruled that her feeding tube could be removed and she died on March 31, 2005, but not before a media spectacle that involved the governor of Florida, state senators, and the sitting president. After her death, the Schindlers, devout Catholics who considered Terri to be severely disabled, looked for a way to help others in their situation. As Bobby Schindler, Terri’s brother, wrote last year:

“After Terri died, my family’s experience, contesting this powerful right-to-die movement, led us to establish the Terri Schiavo Life & Hope Network, which seeks to raise public awareness of the looming culture of death, and to educate the public about care potentialities. Most importantly, however, is to help families in situations similar to what we experienced—loved ones in danger of being killed, like Terri.”

Bobby Schindler is now president of the organization and a full-time advocate for “pro-life” ideals. His work has been endorsed by Catholic archbishops and evangelical leaders alike. And it is because of Bobby Schindler and the Life & Hope Network that Jahi McMath is in a hospital bed in an apartment in New Jersey.

After the news broke that McMath’s parents refused to remove her ventilator, they got in touch with Schindler, who helped the parents find a suitable facility for their daughter. New Jersey, because of the state’s religious exemption for brain death, was the ideal choice. Cases like Jahi’s are incredibly rare. But they are often fueled by political and religious ideologies that conflict with standard medical practice. State laws, which govern how those ideologies are applied to individual cases, are now at the heart of a series of lawsuits; if her parents can prove she is alive, if they can invalidate the California death certificate, they can return to their home state and receive funding for their daughter’s continued treatment.

Jahi was only 13 years old at the time of her fatal operation. Now, two years later, doctors are concerned that public perception will be muddled or swayed regarding the general medical definition of brain death. Already Bobby Schindler has conflated his deceased sister’s illness with Jahi’s in an article for Time magazine. Doctors and bioethicists have been busy with brain-death conferences the past two years, asking their colleagues what Jahi’s case bodes for their ethical standards.

But religious actors have found a compelling issue in a young child, her desperate and grief-torn parents rightly skeptical of the hospital and doctors whose treatment has harmed their daughter. If the Jahi case results in California rescinding the girl’s death certificate, we may see a broader political push for religious exemptions from certain kinds of deaths. The ramifications are hard to predict. In January, a California judge issued a tentative ruling that allows Jahi’s family the chance to prove that she is alive. Either they will have to present medical information that contests Jahi’s brain-death diagnosis, meaning her brain death was a diagnostic error, or they will have to show that brain death is not death. Either would will be, for the family of Jahi McMath, some kind of miracle.

Ann Neumann is the author of the new book The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America published by Beacon Press.