CHICAGO — Inmates at the Cook County Jail served more than 200 years’ worth of unnecessary time behind bars last year thanks to an overworked criminal justice system.

While the killing of Laquan McDonald by a cop and the accompanying Justice Department investigation of the Chicago Police Department have drawn much attention in Chicago, the flood of problems inundating the Cook County Jail have received scant attention.

The wait for a case to reach conviction can be so long that many of the jail’s inmates serve more time in Cook County than they are eventually sentenced to spend in prison, what’s known as “dead days.” For instance, if an inmate is convicted to 100 days in state prison, and spends 300 days in Cook County waiting for their case to reach conviction, they will have served 200 dead days.

Last year, inmates served 79,726 dead days at a cost of $143 per person per day in 2015. In other words, people spent 218 years’ worth of unnecessary time in jail at a cost of $11 million to taxpayers.

Sheriff Tom Dart’s office, which runs the facility, is making efforts to address the problem but its task is monumental. With an average daily population of 9,000, the jail is only slightly smaller than Rikers Island in New York, a city twice as populous as all of Cook County.

In addition to the dead days found by Dart’s office, a year-long Daily Beast investigation found at least five men spent more than 500 days behind bars before being convicted or released.

For instance, taxpayers spent more than $100,000 to keep Donte Kenney in jail for 802 days while he awaited trial for pointing a gun at a Chicago police officer in 2013.

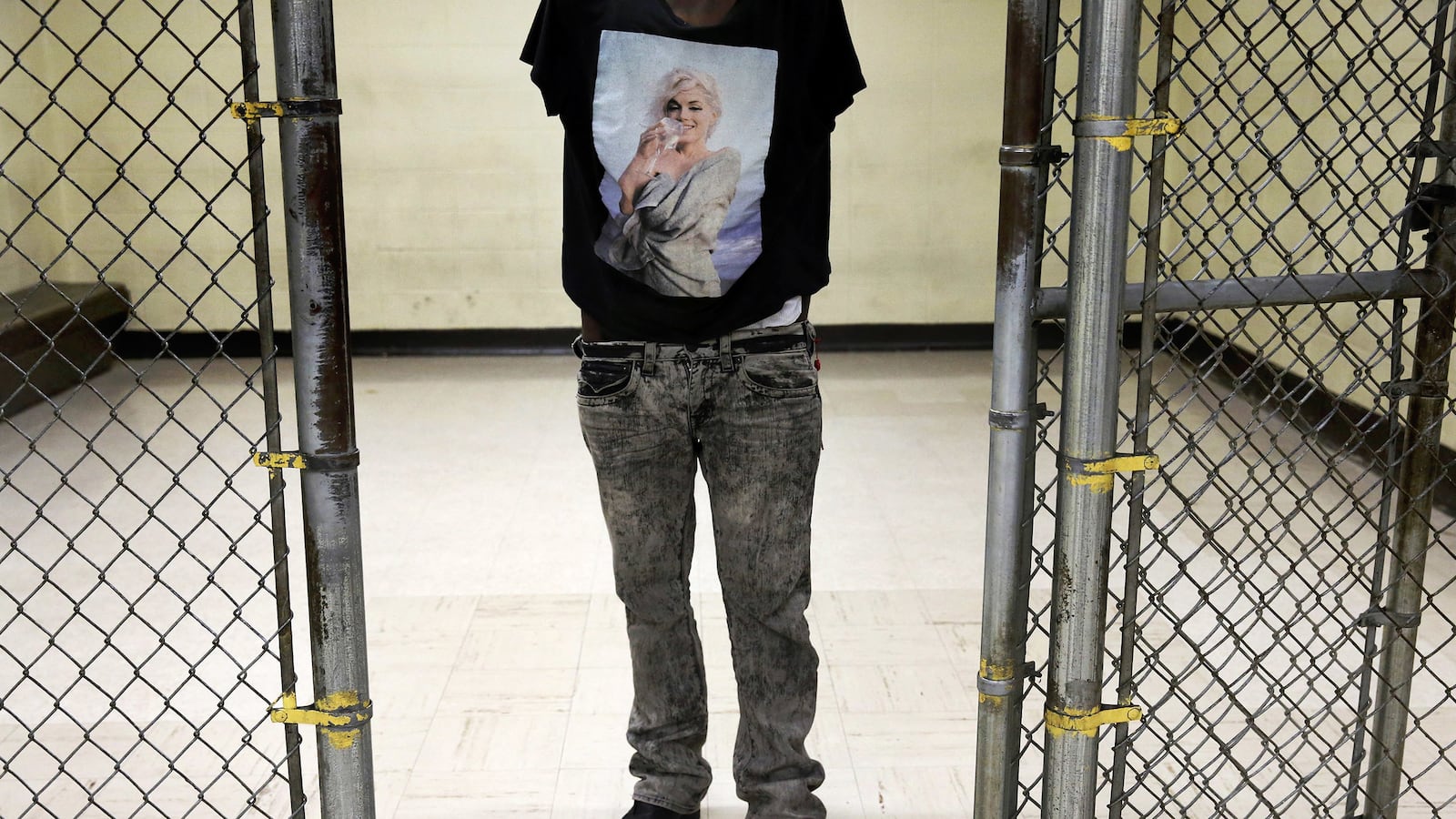

Along with Kenney, there is Andreas Oliver, who spent 715 days in jail before he was convicted of breaking into an ex-girlfriend’s home and assaulting her. Basir Edwards spent 553 days at Cook County before being sent to state prison for his role in a shooting in which he tried to hide a gun from police. Sylvester Walker did 514 days before receiving probation over a drug charge.

But there is another category of people who spend long stretches in jail only to see their cases are dismissed.

Froylan Ramirez, also a member of the 500 club, falls into this category for his St. Patrick’s Day 2014 DUI arrest in Chicago. Ramirez’s case was dismissed 514 days—and $73,502—later and he was sent home.

By comparison, the maximum legal penalty for DUI in Illinois is $25,000.

Aside from the monetary cost, there is an incalculable human cost for men like Ramirez.

Maybe he had a job when he was locked up, a job he almost surely lost while spending a year behind bars for a crime the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office wouldn’t even prove he committed. A marriage? Ben Breit, spokesman for the sheriff’s office, wonders. Perhaps that ended too while he was locked up for so long.

“Society is not safer because of it. He is not better off for it,” Breit said. “To what end did this happen?”

Meanwhile, Willie Mance is still waiting for his case to be finalized after 777 days. A convicted gun felon, Mance allegedly tried to run over two Chicago police officers while drunkenly driving a car that wasn’t his. As of Thursday, his stay in Cook County has so far cost taxpayers $111,111.

“Frankly, that’s what this jail is for,” Breit said of alleged criminals like Mance. “It’s pre-trial detainment for people who are too dangerous to be let into the community.”

But for 777 days?

“That makes no sense. It’s just insane,” Breit said.

One of the reasons men like Kenney, Mance, and Ramirez spend so much time at the jail is they can’t afford to get out. In all three men’s cases, lengthy criminal records likely played a role in a judge’s decision to set high bond amounts. Then it’s a choice between spending money to get out of jail and spending money on a private attorney.

“You can’t do both when you’re poor, and it’s a devastating choice,” Breit said.

Without a private attorney, defendants are in the hands of the Cook County Public Defender’s Office. As of late last year the office had 503 attorneys—a number far short of what it should be, according to Amy Campanelli, president of the office.

“If I could, I would have twice as many staff as we now have, but that is not feasible,” Campanelli said in an interview with the National Association for Public Defense last year.

Lester Finkle, a spokesperson for the public defender’s office, said many of his clients can’t afford bond, and many of them are accused of nonviolent crimes.

Among those non-violent offenders is “D.E.,” who in 2014 spent 86 days in jail at a cost to the taxpayers of more than $12,000 for trespassing at O’Hare International Airport, a common charge for the homeless who are looking to sleep there, according to Breit.

D.E. whose anonymity has been maintained as part of a case study program by Dart’s office, is also among a significant portion of the jail’s population who is nothing more than a vagrant and a petty thief; he once spent 28 days in jail for stealing a drink and a bag of cookies.

The $4.58 theft cost taxpayers $4,000.

Non-violent offenders like D.E. were addressed by Dart when he pushed for a law passed last year that requires a speedier process for inmates who don’t pose a serious danger to the public.

The “Rocket Docket” allows jail officials to identify non-violent offenders with relatively short criminal histories and help expedite their cases through the courts system. Within 30 days of being assigned to a judge, those who have stolen less than $300 worth of goods or been arrested for petty trespassing must have their cases heard.

If the case can’t be heard within its first month, a judge must make a decision to free the inmate under the agreement that they show back up in court at their next hearing date, or put them on house arrest—both ways to keep them out of the jail.

“We’re seeing judges making far greater use of electronic monitoring for non-violent offenses,” Breit said. “But that doesn’t help for people who are here for murder who are here incredible amounts of time.”

Ramirez, Kenney, and Mance are bad men. They are career criminals in a city struggling mightily for law and order amid an uptick in shootings and murders and through-the-roof homicide rates. But they are also American citizens, and as such are supposed to be afforded the speedy and public trials we tend to take for granted.

“So many jails are out of sight out of mind. But people tend to forget that our inmates here are pre-trial; they have yet to be convicted and yet they’re staying here for large amounts of time,” Breit said. “The system needs deep reform.”