I used to work in the United States drone program. I did not “push the button” or guide the missiles, but I was one of the many faceless technicians who executed the so-called War on Terror from my home state of California. What I learned during my time in the Air Force drone program ultimately made me want to leave it in 2012: The U.S. drone program is immense and powerful in its scope, and in urgent need of more extensive transparency, oversight, and accountability.

Since the drone program began, the U.S. military has been keen on keeping data related to it under wraps. Due to the near-absence of official information, drone strike statistics answer few questions and raise many more. For example, when the Obama administration released the first official estimates of those killed in strikes during President Obama’s presidency, they only included those that took place outside the conventional wars in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, leaving human rights advocates and media organizations trying to fill in the blanks.

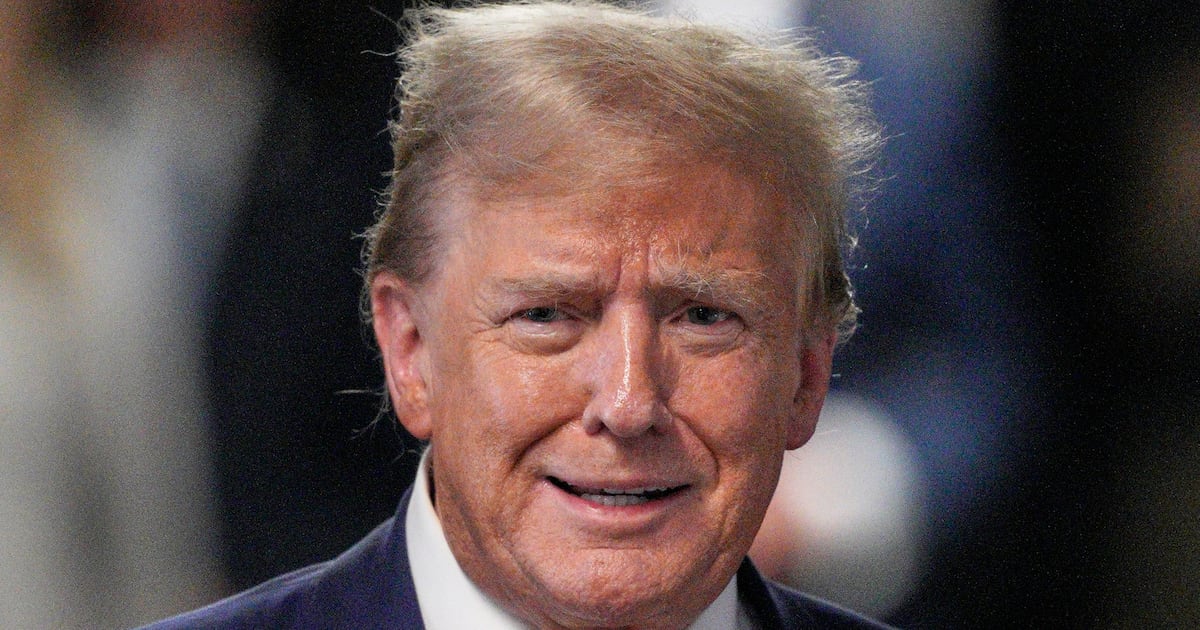

Under President Trump, whose stated opinions on transparency vary from negative to non-existent, the problem is only getting worse. However, the incredible work of accountability organizations such as The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in recent years allows us to fill in some of the blanks. Looking at drone strike data from Afghanistan, starting at the beginning of Trump’s presidency nine months ago, there have been a minimum of 2,353 confirmed strikes in Afghanistan, with between 684 and 1081 people reported killed in them, including anywhere between 51 and 116 civilians and children.

Earlier this month, The New York Times reported that the White House appears to be in favor of giving the Central Intelligence Agency unprecedented authority to conduct drone strikes in Afghanistan. To place this secret killing power in the hands of the CIA, a civilian agency known for its long history of participating on behalf of U.S. interests in foreign conflicts, is irresponsible and immoral. It might even be illegal.

CBS legal analyst Andrew Cohen put it this way: The CIA drone program is legal because the U.S. government said it was legal. That still doesn’t actually make it legal. To be deemed legitimate under international law, (PDF), a targeted killing using drones must successfully prove this killing is in self-defense, is happening in armed conflict, is necessary, and is proportional.

After the 9/11 attacks, the White House tried to argue that drone strikes fit those criteria. The Bush administration said that a 1974 presidential directive banning assassinations would not prevent the United States from acting in self-defense. White House and CIA lawyers believed that the intelligence finding was constitutional because the ban on political assassination does not apply to wartime. They also contended that the prohibition does not preclude the United States taking action against terrorists.

On the other hand, human rights groups argued that the CIA now functioned as a military force beyond the accountability that the United States has historically demanded of its armed services. Although both the Joint Special Operations Command and the CIA’s drone strikes presumably target the same people, Council on Foreign Relations’ Micah Zenko noted, “the organizations have different authorities, policies, accountability, mechanisms, and oversight.” Splitting the drone strikes between the two programs was apparently intended to allow the plausible deniability of CIA strikes, while giving the U.S. government the guise of accountability and transparency.

JSOC drone operation reports are guided by Title 10 armed forces operations and a publicly available military doctrine. They are bound to a comprehensive list of rules, standards, and definitions, whereas the CIA as a civilian clandestine organization doesn’t even have to acknowledge its drone program, let alone provide public explanation about who shoots and who dies, and by what rules.

The different reporting requirements for these two operations have even confused congressional committees. The foreign relations committees—tasked with overseeing all U.S. foreign policy and counterterrorism strategies—have formally requested briefings on drone strikes, only to be repeatedly denied by the White House.

This ambiguity that allowed the CIA to conduct drone strikes until 2013 left both the U.S. public and the citizens of the countries the CIA is striking with no answers, nor an avenue to get them. A particularly heartbreaking instance of this is Kareem Khan, a Pakistani journalist, who attempted to sue two CIA agents in Islamabad in 2016 over the agency’s alleged killing of his son and brother in a drone strike in Pakistan. These murders took place on New Year’s Eve 2009, almost seven years ago, in what was locally reported to be a mistake by U.S. forces targeting a Taliban commander. Khan told Al Jazeera, “They tell the world that they’re killing terrorists [but] they’re killing innocents.”

Khan’s brother and teenage son are just two of the unknown amount of casualties in the CIA’s covert drone war. The most notable exception has to be Giovanni Lo Porto, an Italian aid worker, who along with American Warren Weinstein, was killed accidentally by a CIA drone strike on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. The CIA was targeting an al Qaeda base, where they were being held. After much scrutiny, the U.S. paid €1M to Lo Porto’s family. Yet, the U.S. government still never acknowledged guilt; instead this was labeled a “condolence payment.” Jennifer Gibson, from human rights group Reprieve, said of this payment: “The Lo Porto and Weinstein families are the only families that have been acknowledged and apologised to by the administration. Thus far there hasn’t been a single Pakistani or Yemeni family that has received the same acknowledgment.”

Now tell me, how is the murder of civilians like Kareem Khan’s son and brother, who were murdered in their home on New Year’s Eve, justified as “self-defense,” “happening in armed conflict,” “necessary,” and “proportional?”

The U.S. needs a consistent strategy in its so-called War on Terror, with consistent policies and strategic objectives that are aligned with other ongoing military and diplomatic activities. If the CIA is conducting these strikes in the darkness of “plausible deniability,” then how is that possible? This is why lethal drones should be the exclusive purview of the Department of Defense, and the extent to which there is a need for the covert employment of such, those drones would fall under the auspices of the Joint Special Operations Command. Having armed drones in the CIA is part and parcel of the corruption of the agency’s very reason for being—the collection of foreign intelligence, not the assassination of suspected terrorists.

Transparency and accountability are necessary to keep the immense power that drones wield in check. As former government officials and national security experts stated in a letter to Secretary of Defense Mattis this spring, the oversight needed is simply not possible if the authority to use drone strikes is in the hands of the CIA. In particular, the U.S. government cannot legally acknowledge covert actions undertaken by the CIA, which means that simple information like “here’s what we did, here’s why we did it, here’s our assessment of what happened,” is no longer possible.

Without this information, keeping an eye on the proportionality that is legally required is exceedingly difficult, when it is possible at all. For example, the Pentagon is required to document any and all civilian casualties that occur as a result of its operations; the CIA is not. Back when the CIA had the power to conduct covert drone strikes, they were hunting Baitullah Mehsud, Pakistan’s top Taliban leader. It appears to have taken 16 missile strikes, and 14 months, before the CIA succeeded in killing him. During this hunt, between 207 and 321 additional people were killed. These numbers are based on independent accounts, not CIA information. In all reality, we most likely will never be able to get a complete picture of whom the CIA killed during this campaign.

The United States’ inability to take responsibility for the consequences of this program, especially when lethal mistakes are made, leads to a counterproductive national security policy that makes the U.S. less safe. For every innocent killed, the chance of blowback here in the United States and abroad increases.

Many terrorists in the United States have been outspoken about their motivations for planning attacks. Faisal Shahzad, the failed Times Square bomber who was included in the FBI-JRIC Assessment, explained his own reasoning in court: “I want to plead guilty 100 times because unless the United States pulls out of Afghanistan and Iraq, until they stop drone strikes in Somalia, Pakistan and Yemen and stop attacking Muslim lands, we will attack the United States and be out to get them.” This is the result of failed counterinsurgency policy and with the CIA free to drone anywhere around the globe, I believe the problem will only increase as the fixes get fewer.

When I spoke to General Stanley McChrystal, the former commander of all U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, during the filming of the documentary National Bird, he told me, “You have to understand how people perceive things, it’s one thing to do things and it is another to anger a population in the process… because you are going to create some ill will [using drones]...”

Neither he nor I think drone technology will completely go away, but one thing is clear; if authority is given to a clandestine agency, an explanation will not be forthcoming. The Pentagon, at its very worst, has a form of global governance that can be viewed by the public and is ruled by a set of internationally recognized laws. Do we really want this unlimited power used in secret; do we want to set this precedent?

The Guardian recently discussed how we are at risk of returning to a world where might is right and war is legal, but we are already there—and it’ll get even worse if the CIA gains this authority in Afghanistan.