With the launch of Tesla’s Model 3 electric sedan, inventor Nikola Tesla is about to become more famous than ever—and for all the wrong reasons, being compared to Henry Ford, the car guy, not Thomas Edison, the electricity guru.

Tesla may have outdone Edison in wizardry, but not in business—Tesla died broke and broken. In a small, well-played part in The Prestige, David Bowie captured the eccentric, tortured, moralistic, futuristic Tesla. Today, as we wander around, swimming in invisible waves transmitting energy all around us, as we spend our lives addicted to wireless devices catching a hail of transparent messages, we live in Tesla’s world.

Although many say Tesla invented the twentieth century, it is more fitting to say he invented the twenty-first century, Kenny Breuer, Professor of Engineering at Brown University, explains. Breuer says most of Tesla’s inventions became “winners” later, “so for years no one really appreciated his achievements. Electric motors, wireless communication, wireless powering, those are all Tesla’s ideas that didn’t really dominate until the rest of technology could catch up with his brilliance.”

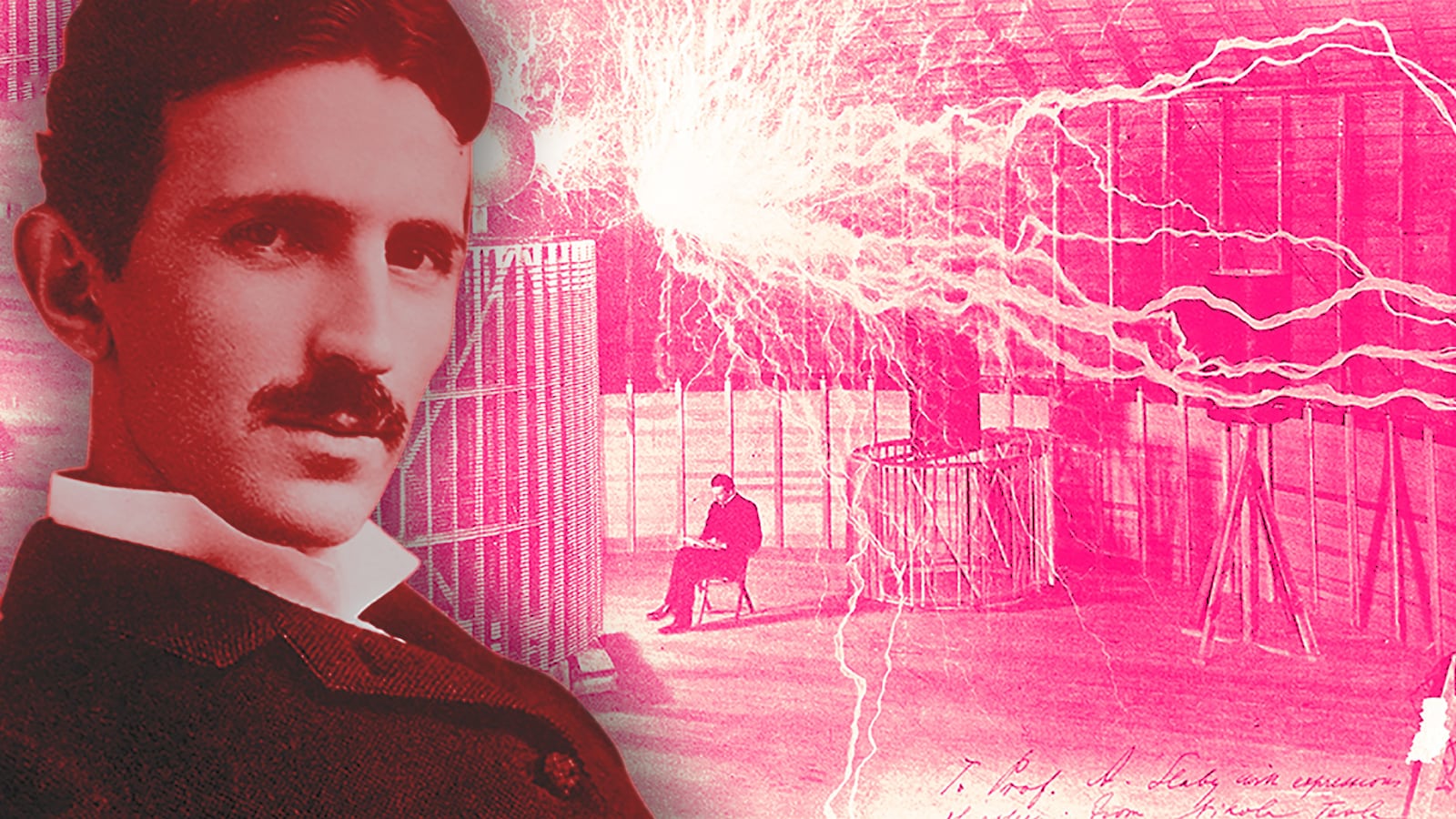

Fathoming a mind that generated more than 700 patents and countless applications, from the Tesla coil to remote control to radar to smart bombs, is overwhelming. Focusing on one defining moment in his madcap life illustrates his virtuosity. In 1899, he moved to Colorado Springs to prove something we take for granted today: you don’t need wires to move energy from source to destination; nature, properly managed, can do the trick.

By this time, midway through a life that began in Smiljan, Croatia, in 1856 and ended in Manhattan in 1943, Tesla was already immortal. He had immigrated to America, worked with Thomas Edison, broken up with Edison—and outdone Edison, conceptually if not practically.

Edison, associated with the phonograph, the light bulb, the Dictaphone, among so many other innovations, had in 1882 established the Edison Illuminating Company to bring 110-volt direct current into businesses and homes to power the incandescent lamps he had invented. In the ensuing War of the Currents, others, spearheaded by Edison’s competitor George Westinghouse, preferred AC to DC, alternating current to direct current.

Requiring a particular power source, direct current could only be transmitted within a limited area. Alternatively, Professor Breuer explains, “in an AC device, the voltage oscillates, alternating between positive and negative. In response, the current also oscillates, moving forwards then backwards through the circuit.” That makes transmitting power over vast areas, easy cheap, safe.

Tesla, who treated invention as artistry, was inspired by Goethe’s celebration of sunset in Faust to create what became the induction motor harnessing electromagnetic power to alternate current. Tesla arrived in New York in 1884 with four cents in his pocket but priceless assets: a sterling mind, a letter of introduction to Edison, and pride in his Serbian and European heritages. He would recall: “What I had left was beautiful, artistic and fascinating in every way; what I saw here was machined, rough and unattractive.” The letter, from an Edison business associate read: “My Dear Edison: I know two great men and you are one of them. The other is this young man!"

Within a few months, the two great egos tired of clashing. By 1888, Tesla had sold his AC ideas to Edison’s enemy Westinghouse. Ultimately, AC overpowered DC.

Edison versus Tesla pitted perspiration against inspiration, the American tinkerer versus the European theorizer. With Edison, genius emerged through repeated, obsessive, tryouts. By contrast, “I get an idea I start at once building it up in my imagination,” Tesla explained in his autobiography. “I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind. It is absolutely immaterial to me whether I run my turbine in thought or test it in my shop… the results are the same.”

While hobnobbing with Manhattan socialites, Tesla kept imagining, and creating, often succeeding conceptually while failing practically. In 1893, he introduced wireless transmissions. Five years later, he anticipated radio by transmitting electro-magnetic waves from one set of circuits to another, set on similar frequencies. Alas, once again, a more practical rival, Guglielmo Marconi, received more historical credit for those breakthroughs. Like Edison, Marconi excelled at commercializing and publicizing his work.

By 1899, Tesla was obsessed with building a huge power-emitting transmitter that could fulfill what he called “one of my fondest dreams”—generating wireless transmission. Vowing to send signals from Pike’s Peak to Paris, Tesla moved to Colorado Springs, where the air is thin and the lightning is plentiful—he once recorded 12,000 bolts in three hours. Struck that the electrical pulses he measured from lightning didn’t fade even as the bolts flew away, Tesla had another Eureka moment.

In his journal, he noted: “It was on the 3rd of July—the date I shall never forget—when I obtained the first decisive experimental evidence of a truth of overwhelming importance for the advancement of humanity.” His explanation: that “stationary waves” within the earth helped conduct the energy through the earth itself. The scientific consensus today is that the atmosphere not the earth is the great conductor; nevertheless, Tesla anticipated our wireless world.

To approximate the power of lightning, Tesla built a crazy contraption with a 142-foot metal mass and a huge power coil, a Tesla coil. On the big day, his technician opened the switch and BOOM! BUZZ! CRASH! Indeed a human being had created a magnificent, blue-tinged, sky-filling electrical storm. He also crashed the city’s power grid, plunging Colorado Springs into darkness immediately after bathing in that exceptional light.

These experiments confirmed this crazy vision which is now an accepted truth. Tesla envisioned “the inter-connection of the existing telegraph, telephone, and other signal stations without any change in their present equipment. By its means, for instance, a telephone subscriber here may call up and talk to any other subscriber on the Globe. An inexpensive receiver, not bigger than a watch, will enable him to listen anywhere, on land or sea, to a speech delivered or music played in some other place, however distant.”

Encouraged, Tesla returned to the East Coast. He built the 187-foot Wardenclyffe Tower in Shoreham, New York, until nervous investors shut him down. That failure triggered a nervous breakdown, and a long decline. The descent still sparked plans for a bladeless turbine, radar, a biplane that ascended and descended vertically, and a Time cover on this 75th birthday honoring him with the phrase “All the world’s his power house.” Believing that chastity kept his energy focused on his inventions, Tesla never married. He slept two to three hours a night—dozing off occasionally other times.

By now, knowledgeable readers who know that Tesla cars use AC induction motors, will understand why Elon Musk named Tesla Tesla. Only it was not Musk, it was one of the company’s co-founders before Musk muscled him aside, Martin Eberhard. I guess in the twenty-first century too, the celebrities aren’t always the ones who started it all—or got it right.