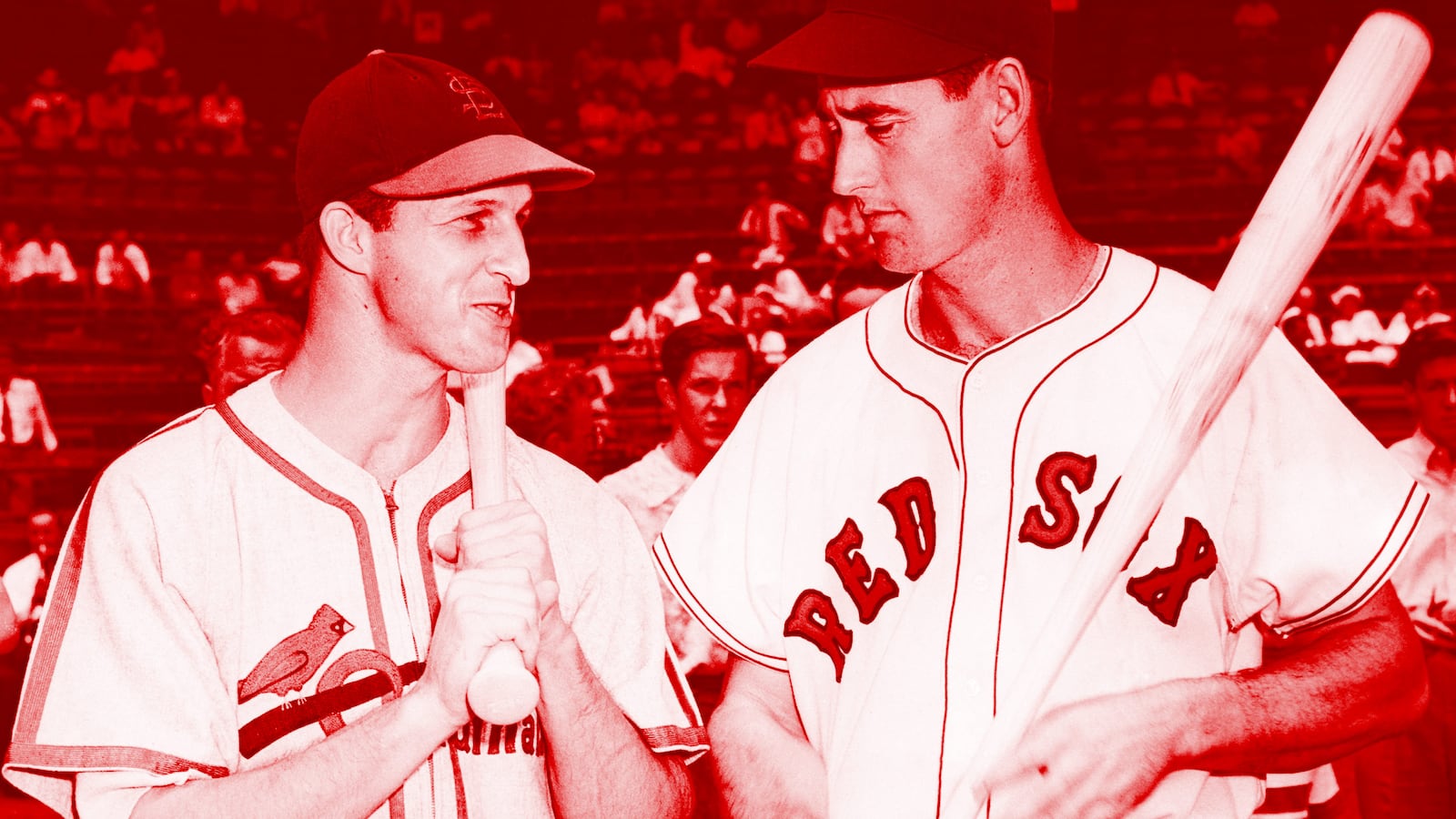

In 1941, Ted Williams, the most fearsome hitter in the American League, came to the plate in the ninth inning of the All-Star game at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium with two out, two on, and the AL trailing by a run. With two strikes, he drove a ball into the right field stands for a game-winning home run.

In 1955, Stan Musial, the most feared hitter in the National League, came to bat in the 12th inning of the All-Star game at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, with the score tied 5-5. On the first pitch, Musial drove the ball into the left-field stands for the game-winning home run.

In 1970, Cincinnati’s Pete Rose, who would end his career with more base hits than anyone whoever played the game, won the All-Star game in the 12th inning by slamming into the Indians’ catcher Ray Fosse in a violent home plate collision.

Anyone tuning in Tuesday night in the hope of seeing Aaron Judge or Daniel Murphy or Bryce Harper end the game with a similar late-inning blast is absolutely guaranteed to be disappointed. Why? Because the way the All-Star games are now played, the starting players—the ones voted onto the line by the fans, the ones those voters want to see—are gone well before the middle of the game. Last year, only eight of the 41 position players who actually played in the game got up as many as three times; the vast majority made it to the plate once or twice. (Williams and Musial hit their respective homers on their fourth at bat). This means that by the time the game is an hour and a half old, the most celebrated players in the game are in the dugout, in the shower, or at a restaurant.

You can understand why. Under current rules, at least one player from every team must be named to the squad; and with 30 teams in the majors—a huge increase from the 16 that were around for the first 58 years of the modern era—that’s a lot more players crowding the dugout. And there’s an understandable impulse to have as many of them actually take part in the game, as opposed to letting them just sit on the bench.

Maybe it’s a coincidence that, as the starting players have seen less playing time, the popularity of the event has plummeted. After all, inter-league play has made the once-exotic notion of a top AL pitcher challenging a top NL batter commonplace. The sheer omnipresence of baseball, thanks to MLB, ESPN, Fox Sports, and live-streaming, has created something of a glut on the market. A curious fan no longer has to wait for the All-Star game to see players from distant cities. And baseball’s relative impotence in marketing its stars—something the NBA has been doing since the days of Magic, Kareem, and Bird—has been a a serious drag.

Whatever the reason, the All-Star Game is a shadow of its former ratings self. In 1976, the game drew 36.5 million viewers. Last year (with America’s population 100 million greater than in 1976), the game drew 8.7 million. Its 5.4 ratings was the lowest in the half century of such measurements; and the great majority of viewers, more than five million, were over the age of fifty. And now that victory will no longer mean World Series home field advantage for the winning league, there’s not even a substantive reason to tune in.

Happily, there’s a way to make the All-Star game more compelling, while taking an important step forward in branding. Today, baseball is blessed with a regiment of young, exciting players. Twenty-five year old New York yankee Aaron Judge not only hits a lot of home runs, he hits them far enough to jump start tape measure sales. The Washington Nationals’ Bryce Harper, at 25, is in his sixth All-Star Game. (Mike Trout of the Los Angels Angels, 25, will miss his sixth due to injuries). Twenty-one year old Cody Bellinger is hitting home runs for the LA Dodgers at a Judge-like pace. A simple rule change would make it far more likely that one of these charismatic players, or a more seasoned All-Star like the Astros’ Jose Altuve or the Giants’ Buster Posey, could provide late-inning heroics.

What’s the change? Simple: allow free substitutions after the seventh inning. If the game’s tied or close in the eighth or ninth inning, or if a trailing team is looking for a spark, let the manager send up whomever he wants, even if that player left after the fourth or fifth inning. The knowledge that we may get to see Judge or Harper or Bellinger or whomever come up to the plate again may well keep even casual fans watching until the fat lady sings. If that seems too big a break with tradition, then limit the managers choice to , say, three free substitutions—although even purists should have little problem with such a rule change.

It is, after all, an exhibition game.So why not give the game’s most attractive selling points the chance to exhibit themselves as much as possible?