When Usaama Rahim was a teenager, he didn’t like his name.

“My name is Usaama, but don’t call me that,” he told a friend who knew Rahim well throughout his late teens and early twenties. “I like going by Rahim.”

“The first thing people think of, they think of a terrorist—you know, like Osama Bin Laden,” he told her.

“He loved his name. It’s not like he didn’t like it. He just didn’t like what people took as the stereotype of it being,” explained Claire, the friend whose name has been changed to protect her identity. Although she once knew Usaama Rahim and his nephew David Wright well, she fears what they may have become, and worries that their friends may seek retribution for speaking out.

According to law enforcement, Rahim, 26, was killed harboring a plot to behead police officers and wielding a foot-long knife. Wright allegedly supported his plan, and is facing obstruction charges for his involvement. There is one other individual in Rhode Island, left unnamed in the criminal complaint, who allegedly discussed the plan with them, but who has not faced charges.

Usaama Rahim’s aunt told reporters he was most likely scared of the officers following him so early in the morning and threatened by the “current slaughter of black men across the nation.”

The FBI says Rahim was acting as a warrior for ISIS.

Claire, who communicated with Rahim a few months before his death, believes the answer may be somewhere in the middle.

When Rahim wrote to her in a Facebook chat in March—which has been provided exclusively to The Daily Beast—Claire says she wasn’t sure what he was trying to say at the time.

Months later, the chats—ones that advocate for stoning adulterers and killing those who defame “the religion of Islam or the Prophet Muhammad”—now offer a glimpse into his shift into radical Islamic ideology.

In February of this year, Claire had reached out to him to see if he wanted a job as a podcast show host. She heard that a startup was looking for a host on a show about being a young Muslim in America.

But since the two grew apart over the last several years, she says he’d gotten more serious about his faith. He started going by Usaama, sometime in 2009. He’d been passionate about discussing his beliefs, too—to Claire, her friends and family, and even to the friends he’d made on an online chat community called Paltalk. Despite his temper and impulsiveness, which could often lead Rahim into problems, she still thought the job would be a good fit.

After all, his older brother, Imam Ibrahim Rahim, 20 years his senior, had become prominent speaker in the community, speaking out adamantly against the Tsarnaev brothers and the bombing attacks in Boston. She had seen him on CNN. Maybe Rahim could follow in his brother’s footsteps?

“My question is would you be interested in it?” she asked.

“Hmm. Sure,” he wrote back on February 13th.

But in late March, when he wrote to follow up on the position, Claire had to tell Rahim the radio show was a bust. They weren’t going to do a show about Islam after all, but she wanted to suggest that he should start his own.

“If your anything like the passionate person I knew once before when it concerns religion, I believe you could do great good to break down misconceptions about what it means to be Muslim,” she wrote.

That’s when Rahim informed Claire that he now had a very different view on Islam and the world than the one he revealed to her when the two were closer.

“I still have my passion and my impulsion resurfaces at times. But the reality is that my understanding of Islam has changed greatly. I’ve seen what you’ve posted on your page regarding political matters which I now favor. I don’t think I am the same person you once knew, but it’s good to have memories that are positive. I don’t think i’ll be starting my own podcast solo, but it is a nice thought and I appreciate the encouragement and opportunity.”

Claire says she wasn’t quite sure what he meant by “political matters which I now favor.” She had been posting a lot about ISIS—condemning the group for burning ancient scrolls, raping women, and killing innocent people—but she didn’t think he was talking about that. Maybe he was finally starting to agree with her liberal point of view, Claire thought.

“its fab to hear you favoring some of the matters I have posted. This world needs more freethinkers!” she replied.

That’s when Rahim sent Claire a final screed, endorsing the deaths of those who defame “the religion of Islam or the Prophet Muhammad.”

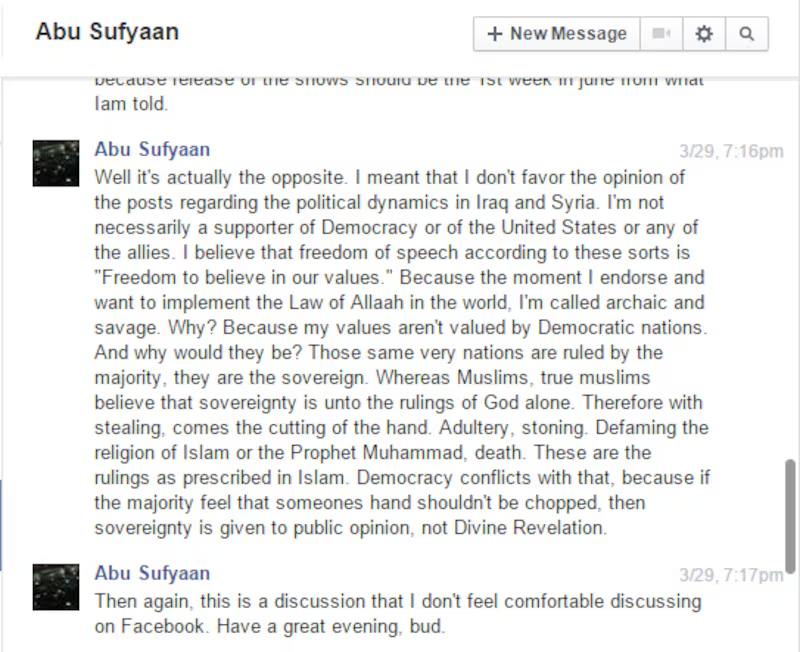

“Well it’s actually the opposite. I meant that I don’t favor the opinion of the posts regarding the political dynamics in Iraq and Syria. I’m not necessarily a supporter of Democracy or of the United States or any of the allies. I believe that freedom of speech according to these sorts is ‘Freedom to believe in our values.’ Because the moment I endorse and want to implement the Law of Allaah in the world, I’m called archaic and savage. Why? Because my values aren’t valued by Democratic nations. And why would they be? Those same very nations are ruled by the majority, they are the sovereign. Whereas Muslims, true muslims believe that sovereignty is unto the rulings of God alone. Therefore with stealing, comes the cutting of the hand. Adultery, stoning. Defaming the religion of Islam or the Prophet Muhammad, death. These are the rulings as prescribed in Islam. Democracy conflicts with that, because if the majority feel that someones hand shouldn’t be chopped, then sovereignty is given to public opinion, not Divine Revelation.”

Minutes later, Rahim added this:

“Then again, this is a discussion that I don’t feel comfortable discussing on Facebook. Have a great evening, bud.”

At this point, she says, she was starting to get nervous.

“I do respect your right to have such opinions! But Im still for democracy and peace. As lame as it may sound I wish we all could live in harmony,” Claire responded.

Rahim then sent his next message at 7:56 p.m. on March 29th.

“Okay. I appreciate the opportunity. Thanks again. And if you are an advocate of peace, then don’t elect cowboys into presidency in shaa Allaah. :)”

It was the last time they spoke.

***

When Claire and Usaama first met in 2007, the year after Rahim had graduated from Brookline High School, he was passionate about symbolic painters like Gustav Klimt, and nordic death metal bands like Stratovarius and Night Wish.

“He would always say, ‘I can’t believe you’re listening to the Smiths. Listen to this! This is the truth!’” Claire said he told her.

Rahim, Claire says, was ambitious, generous, and impulsive. She once saw him give a homeless couple $60 in cash.

“He wanted to have a business where he could take some of the funding and support those who were pretty much the most down and out—those who needed food, those who needed shelter,” she said.

Claire felt his ambitions may have been intertwined with his faith. “Zakat,” or giving to the poor is one of the five pillars of Islam. At the time, however, she says he wasn’t as open about his religion.

“I don’t want them to know I’m Muslim,” he told her. “But when they look deeper into it maybe they’ll see that all Muslims aren’t bad or that every person deserves respect and kindness.”

Sometimes his ideals felt unobtainable, almost crippling. “He used to say, ‘it’s so much.’”

Teenage years are always a time of transition, but for Rahim, his search for identity was especially difficult and pronounced.

He was the youngest of five children. His mother, Rahima Rahim, a nurse, was born in Brooklyn and converted to Islam in the “civil rights era” according to a novella she wrote, obtained by The New York Times. His father, Abdullah Rahman Rahim, was a teacher who frequently taught English overseas.

Though his mother adored and doted on her youngest child, Rahim was rambunctious. He had a quick temper and would frequently launch into verbal tirades, especially on the women in his life.

“He had too much anger and he didn’t want to listen to her,” explained Claire. “She sent him to live with his father in Saudi Arabia.”

“I think his temper came out of arrogance,” explained Sabrina Thomas, whose cousin dated Rahim in 2007. Thomas said he was possessive, and that he didn’t like when his girlfriends had male friends.

“I think his temper was more about, ‘I think I’m right and how dare you contradict my rightness,’” she explained.

Later, Ibrahim Rahim, would counsel him on his anger issues, Claire said.

Around the time he graduated from high school, his mother left his father and moved to Miami. With his father still overseas, Rahim spent a year living with Wright in Boston before moving to Miami to live with his mother and attend Miami Dade College. He would, though, frequently return to Boston to see family.

“He was having adjustment issues,” Claire explained. He felt close to very few people.”

“I have a lot of associates but very few friends,” she remembers him once telling her. Soon, the friends he did have, started to drift away.

Instead, he sought companionship on Paltalk.

It was around late 2008 to early 2009 that Claire began to get concerned about the conversations Rahim was having on the audio and video chat site.

“[Rahim] started saying how he would have arguments with this guy named Joel, and he would call him Joel the Jew,” she said.

The conversations with “Joel” would often irritate Usaama. “After a while he was like, ‘Oh, you know, the Jews are so dumb,’” Claire remembered.

Claire, upset by the hateful rhetoric, called him out.

“I’m just letting it cloud my judgment. It’s just him. It’s not the people. I just can’t stand how he’s talking about my religion,” she said he told her.

“I thought you weren’t into religion as much,” Claire remembers saying to Usaama.

“Well,” she recalls him saying, “I’m Muslim. I’ll always be Muslim.”

Rahim started spending more and more time on Paltalk—hours a day, Claire estimated—and he started becoming more serious about his faith. Where before he only prayed once in a while “to make sure I don’t get in trouble,” now he started praying five times a day, growing a beard, and carrying around the Koran.

Although he previously had complained about the culture shock of moving back and forth from Saudi Arabia, he now talked about his trip with fondness.

“Women there knew their places a little bit better and Sharia Law wasn’t a bad thing,” he explained.

He tried to convert Claire. She said he didn’t want her “going to Hell.”

Soon he started wearing a thawb and a kufi—an ankle length robe and cap often worn by devout Muslims in Saudi Arabia. Claire said the only thing that bothered her about it was how he’d react to people whom he felt looked at him funny. He could get confrontational about it.

“Fuck you. Who do you think you are?” Claire remembers him screaming at those who looked askance.

“You know what? They are the kufar, so what more can I think of them?” he’d tell her. Kufar is an often derogatory term for an unbeliever. “He loved saying that.”

Even after the trip, Usaama would still get into arguments with Joel.

Sometimes his nephew, Wright, would join him, “We tag-teamed and we showed him why his religion was old!” Rahim told Claire.

Wright is a large man, standing about 6’4”. At his court appearance on Tuesday, court marshals needed to use two sets of handcuffs. But, as Claire recalls, he was once sweet and gentle. Although Rahim was his elder by only two years and dwarfed him by about a half a foot, Usaama still played a dominant role in their relationship.

When Wright disagreed with him, Rahim would joke, “You’re my nephew. I’m your uncle. Don’t forget that.”

“Oh, sorry, great one,” Wright would jokingly reply, but he would usually go along with Rahim’s plans.

“He wasn’t deep into his religion but Usaama would tell him, ‘You’ve got to start getting back into it, man,’” Claire said.

Soon Wright started growing a beard too. “Yeah, we’re like beard brothers, man,” said Rahim.

This was sometime in 2010. Around this time, Rahim gave up counseling for his anger issues, on the advice of his friends from Paltalk. Claire and Rahim started growing apart.

***

Five years later, on a cool Tuesday morning in early June, just before 7 a.m., Rahim got out of his car and stepped onto a Boston parking lot. Five members of a Joint Terrorism Task Force got out of their vehicles, too. Coffee was brewing in a nearby Dunkin Donuts. A school bus drove by.

What happened next is still under investigation by a Massachusetts district attorney.

The officers wanted to talk. They had been following him 24/7 for weeks, under suspicion of many crimes, including “terrorism offenses,” according to a criminal complaint and law enforcement sources.

Members of the task force had been listening to his phone, and they say he had been planning a violent attack since May 26th, exactly one week before. They monitored him as he bought a 15-inch Ontario Spec Plus Marine Raider Bowie fighting knife, x-raying the package as it came through the mail.

Rahim called Wright after he made the purchase. “I just got myself a nice little tool. You know it’s good for carving wood and like, you know, carving sculptures… and you know,” he said. They both laughed.

The agents caught Wright saying a sentence they believe sounded like “like thinking with your head on your chest.” The agents think this alludes to ISIS propaganda videos, where beheading victims are often seen with their heads placed atop their chests.

According to the complaint, Rahim and Wright’s first plan was to carry out the attack outside of Massachusetts. The two had traveled to a beach in Rhode Island, and spoke to someone there, although that individual was unnamed in the complaint.

But that morning at around 5 a.m., Rahim changed up his plan. “I’m going to be on vacation right here in Massachusetts,” he told Wright. The agents think “vacation” is code for jihad.

Then Rahim told Wright he was going to go after the “boys in blue”—or, in other words, local cops.

When the members of the JTTF met Rahim in the parking lot on Monday morning, they didn’t have an arrest warrant, but they wanted to talk. They were plain clothed, according to Ronald Sullivan, an attorney obtained by Rahim’s family. They did not have their weapons drawn, according to Boston Police Commissioner Bill Evans.

Then, according to the complaint and statements from law enforcement, Rahim drew his knife. When they asked him to put down the weapon, Rahim yelled “you drop yours!”

Two members of the task force, a Boston police officer and an FBI agent, fired at Usaama Rahim. The shots were fatal.

***

Claire only saw that Rahim “liked” the Islamic State of Iraq on Facebook after he died. It’s unclear if his allegiance to the group went any further than that.

“All we know is that he had been on sites that had traditionally been sites that had been frequented by ISIL,” said Massachusetts Congressmen William Keating, who sits on the Homeland Security Committee and attended a hearing with the assistant director of the FBI’s counterterrorism division Michael Steinbach after the attack.

Although the JTTF had been investigating him for weeks—the FBI even made direct contact with Rahim in November 2013, according to a Facebook post on his wall complaining about the incident—they may not have been able to obtain information that he was actively communicating with ISIS members.

“At a certain juncture, things got dark,” explained Keating, saying there is a concern that he may have been communicating with the group using encryption.

Rahim’s ties to the group are still under investigation, and not all of the information regarding the investigation has been declassified to Congress. The government doesn’t need to prove Wright was linked to the group, however, to charge him with conspiring to destroy Rahim’s cell phone after the attack.

Rahim wouldn’t need to be actively communicating with ISIS to be acting under the group’s orders, either. Two weeks before Rahim allegedly began to plan his attack ISIS put out a call on social media urging supporters to attack the American military, heightening the security level on U.S. bases to Bravo—the highest rating since the tenth anniversary of the September 11th attacks.

“So there is a ‘terrorism gone viral’ side of this,” said Keating.

And even if Rahim was just an ISIS fan boy, that could be just as dangerous.

But if Rahim’s plan was in fact to behead the “boys in blue” like he allegedly said, we’ll never know if he would have carried out the plot.

“He used to be a big talker about certain things,” remembers Claire.

“I would like to think that even if he had a plan to do something like this that, when it came time to enact the plan—just based on the good that he had deep down inside of him—he wouldn’t have been able to do it,” she said.

Despite all his years struggling with anger issues, Rahim did not have a criminal record.

“This is the same person that would sit there and watch some of the saddest little chick flicks and cry.”

But Rahim freaking out and brandishing a knife when approached by five officers, before seven in the morning? Claire believes he could have done something like that.

“He might have not been thinking,” she said, sighing.

“He didn’t back down or take kindly to people, like, trying to throw authority on him. Him and authority figures—they weren’t the best of friends.”