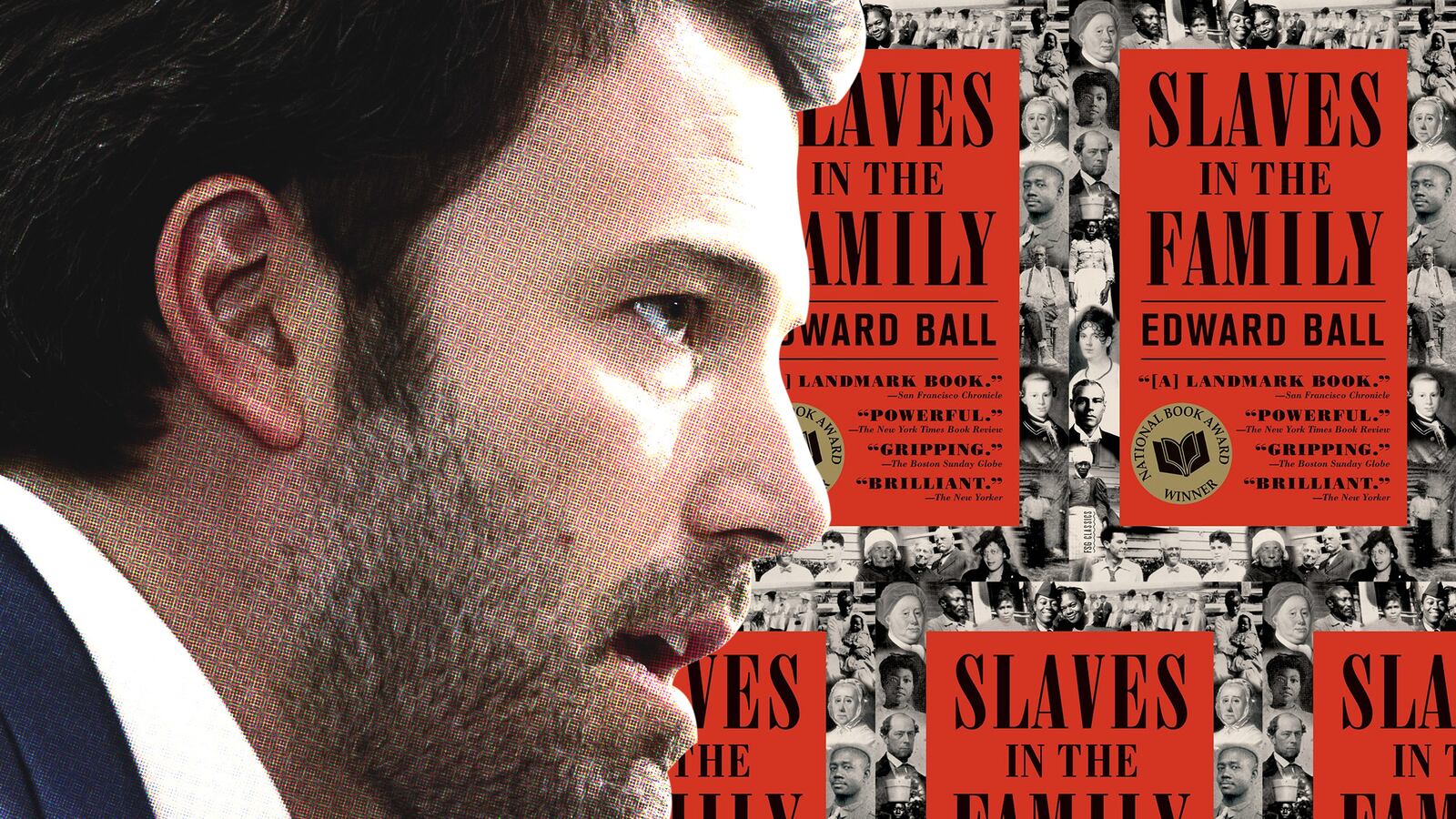

Ben Affleck could learn a thing or two to learn from Edward Ball.

As a participant in Henry Louis Gates’s PBS show about genealogy, Finding Your Roots, Affleck got shellacked in the media this week after he asked Gates to suppress the fact that one of Affleck’s ancestors had owned slaves in 19th century Georgia. Affleck subsequently apologized and outed the offending ancestor on Twitter.

He might have spared himself the whole ordeal had he taken Ball’s path in the first place.

In 1998, Ball published Slaves in the Family, a history of his slave-holding ancestors around Charleston, S.C., and the slave families they owned. In the preface of his new 2014 edition, he,says that he was harshly criticized by some members of his family and cheered on by others. But while he clearly takes no pleasure in making his living relatives unhappy, he has few regrets about writing his National Book Award-winning history.

Ball had no trouble tracking down his ancestors: prominent South Carolinians going back to the 17th century, the Balls made and lost several fortunes growing rice on 25 different farms that sprawled across thousands of acres. They also bought and sold thousands of human beings.

He had more trouble with his living relatives, especially older family members who all partook of the “oral tradition in the Ball family, in which the dead fed the dreams of the living.” Most of those dreams—the Balls never beat their slaves, and Ball men never slept with slaves—proved false, but the kin who told those lies took them for truth and would not be dissuaded.

Tracking down the descendants of the slaves that his family owned proved trickier still, though his search was abetted by the fact that his family had kept excellent records and many of those records survived. Still, because freed slaves often changed their names when they got their freedom, the search was tortuous, involving endless digging into court records, census tracts, city directories, diaries, and letters. The task was, sadly, made easier by the fact that Ball did not lack for subjects. An estimated 4,000 slaves worked the Ball lands over two centuries, and their descendants numbered roughly 100,000 people.

Ball never shies from the complexities of his story, starting with the fact that the black people he meets and interviews are often as unwilling as his white relatives to dredge up an unpleasant past. Time and again, he is the only person in the room with historical records to share, the one person who can plug gaps in the family histories of people who are complete strangers to him.

He is also not afraid to make himself look foolish. At one point, while interviewing an older black woman whose ancestors worked for his, he says, “’So, on Limerick [plantation], your grandfather left a family … went to Stoney Landing, and started another family.’

“’You see, he didn’t “left,”’ Mrs. Frayer corrected me. ‘They sold him. They sold him from Limerick. They been selling you just like you sell a chicken.’”

Embarrassment and awkwardness crop up on both sides of Ball’s story, since the legacy of slavery is still an active and troubling issue in American society. No matter what your feelings are on the subject, confronting it is like brushing against a hot stove. You and I and Ben Affleck all instinctively pull back.

This is not merely a matter of guilt. As Ball writes, “It would be a mistake to say that I felt guilt for the past. A person cannot be culpable for the acts of others, long dead, that he or she could not have influenced. Rather than responsible, I felt accountable for what had happened, called on to try to explain it. I also felt shame about the broken society that had washed up when the tide of slavery receded.”

Miraculously, Slaves in the Family is not depressing, or never for long. Rather, as Ball tirelessly makes his way from one family to the next, interviewing, conversing, informing and being informed, something almost redemptive emerges. Issues are not resolved so much as they are clarified. The very act of confronting the greatest tragedy in American history makes it just a little more bearable.

As one of his sources says, “When I saw the document with the X, with Bright Ma’s signature, I felt I had brushed up against something … I felt I’d hit the past. It was not a chilling feeling. It was a more a feeling of awe, a kind of presence. Praise the Lord. Let it be. Amen.”

Slaves in the Family is an indispensible book.