For two decades, Albania furiously built cement bunkers, steeling itself for the onslaught of nuclear warfare that never came. Today, the country has nearly as many fortifications as it does people.

In 1967, Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha became convinced that his small state would be invaded at any moment, and began preparing.

Already 23 years into his reign, he launched a program of “bunkerization.”

The paranoid dictator had adopted a hardline Stalinist policy and he soon severed ties with both the USSR and Red China.

It became one of the most isolated countries in the world. Convinced of an attack from both the East and West, he poured millions of dollars into building an estimated 750,000 concrete-and-iron bunkers.

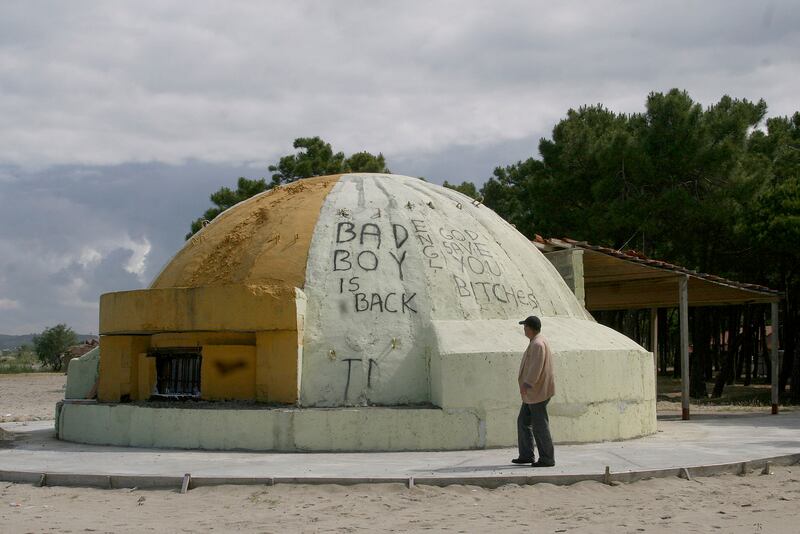

When the mushroom-like structure was first designed, the engineer told Hoxha he was “very confident” in their ability to withstand a tank attack.

As the story goes, the president then told the engineer to stand in his bunker while he fired a tank at it.

He climbed out unscathed, and over the next 20 years, until the dictator’s death in 1985, the bunkers were built virtually everywhere.

Today, there’s around one bunker for every four Albanians, and 24 bunkers per square half-mile.

Many think the massive quantity of funds used to built the sturdy structures could have instead fixed the country’s housing drought at the time. Hundreds died building the structures.

Despite their longevity, few of the bunkers have been removed.

They hide in plain site, buried among the concrete tombs of a cemetery, partially covered with sand on the beach, resting askew in a front yard. Some are in clusters, and the capital of Tirana is basically encircled with them.

While many are rusted and gutted, many are still used consistently for storage or even as a shelter for the homeless.

Young Albanians have found a way to repurpose them in a variety of creative ways.

In a project called Concresco, photographer David Galjaard found one man had turned his into a tattoo studio, while others were used as stores and restaurants.

Since 2010, a small concentration of them have been used for a music festival called Bunkerfest where artists transform the ugly bulbous structures into colorful pieces.

There’s even an entire book devoted to the multiple reuse opportunities for the bunkers.

To make a cafe or bed and breakfast, a group called the Concrete Mushrooms Project recommends adding a window, door lock, and portable electrical functions.

“It suggests that man has the power, through the grotesque and the absurd drama of the past, to cultivate a sense of humor and ease a wounded memory,” the authors write.

The original bunker designer, Josif Zengali, doesn’t think the initial concept was bad—just the excess to which his idea was abused. “There is no country in the world that doesn’t have fortifications,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1999. “But everything in moderation.”

Though the bunkers never saw use as projection from nuclear warfare, they have been made useful in wartime.

During the 1999 Kosovo War, Albanians on the border with Serbia were cleaning up the bunkers and prepping them for possible use.

Some were reportedly used during shelling and later as shelters for refugees fleeing the area.

A few years later, Albania discovered some 16 tons of mustard gas forgotten in a bunker.

While most of the bunkers are small, Hoxhan and his government built an intricate underground network for themselves to house the wartime government in case of attack.

Last year, the Albanian government opened up the largest of these subterranean lairs.

The 106-room, five-floor structure was buried 330-feet deep in the ground outside the capital of Tirana in 1978.

The site was built to withstand the blast of a 20-kiloton atomic bomb, similar to the one dropped on Hirsoshima. That no longer necessary, Albania now has plans to convert it into an artist exhibition space.

Speaking in the subterranean hall, Prime Minister Edi Rama told a group of ambassadors: “We have opened today a thesaurus of the collective memory that presents thousands of pieces of the sad events and life under communism.”