The 911 call of “shots fired” came in shortly after 7:45 p.m. on Saturday night. And when the Tulare County sheriff’s department arrived at a trailer that appeared to be a family compound on the 85-acre Tule River Indian Reservation in the rugged Sierra foothills of California’s Central Valley, they made a gruesome discovery. Inside the trailer they found the bodies of 60-year-old Irene Celaya and her brother, Francisco Moreno, 61. In a nearby shed that doubled as a makeshift bedroom, police discovered the body of Celaya’s younger brother, Bernard Moreno. All had been fatally shot with a .38 caliber revolver. Also among the casualties was Celaya’s 6-year-old grandson, Andrew, who was taken to a hospital in nearby Visalia, then on to another hospital in Fresno.

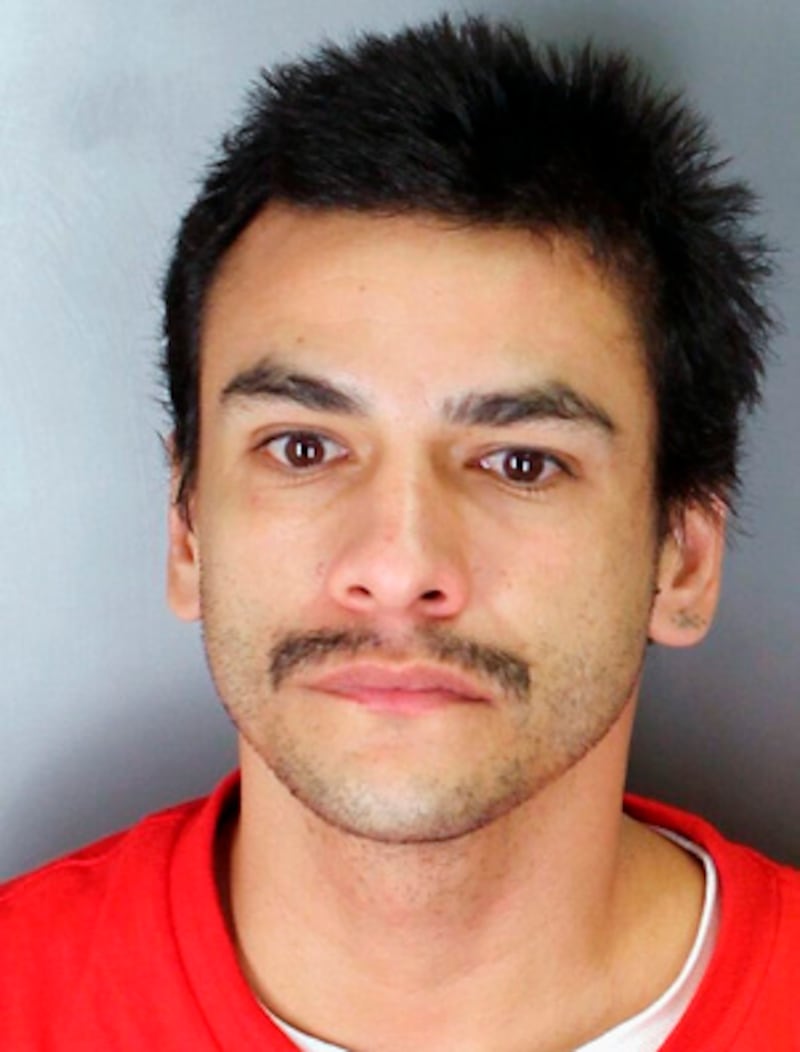

The suspected shooter is 31-year-old Hector Celaya, Irene’s son and the father of Andrew. Celaya, a former custodian at the reservation's Eagle Mountain Casino who had a history of run-ins with the police, fled the scene in a green Jeep Cherokee with his two young daughters, 5-year-old Linea and Alyssa, 8.

Hours later, he was spotted by a deputy in the small town of Lindsay, about 20 miles away. The deputy attempted to pull him over, but Celaya wouldn’t stop, leading police on a slow-speed pursuit. Celaya eventually pulled over to the side of the road where police heard gunshots. They fired back and struck Celaya, at least once.

Before he was fatally shot by police, he fired on his daughters, killing Alyssa, whose name was tattooed on her father’s right leg. “We are not exactly sure when he shot his daughters,” said Tulare County sheriff’s office Sgt. Chris Douglass. “We don’t know if it was the shots we heard from the car or if it happened prior to that.”

Douglass said Celaya was a known meth user, and had a string of previous arrests. In April, police were called to Celaya’s home after the mother of his children called police to report that he was driving drunk with his kids in the car, according to the Associated Press. The following month, a judge ordered Celaya to pay $355 a month in child support to the mother of his children, according to The Fresno Bee. Celaya was granted custody of his children on the weekends. “There had been an ongoing child-custody dispute,” said Mike Blain, chief of the reservation’s police department. “It is still under investigation.”

In addition, Celaya, who was reportedly making about $945 a month, was looking at a year in jail after he was arrested by the Porterville police for drunk driving and being under the influence of drugs in October, the Bee reported. Celaya also spent time in jail for assault and battery in 2008, and a judge ordered him to keep away from weapons as a condition of his three years of probation, the paper said. He also had two additional DUI charges.

The horrific murders shocked the nearby communities and the tight-knit reservation of 1,100, which is located in a remote rural area at an elevation of about 7,500 feet. The reservation, which was established in 1873 and consists of around 300 housing units, is accessible only by one winding 15-mile paved road up into the mountains; the nearest town, Porterville, is 20 miles away.

Murder is a stranger here. “In the seven and a half years I have been with the department, I have not seen an incident like this on the reservation,” Sgt. Douglass said. The most infamous murder on record happened in 1886, when four tribal members killed the reservation’s shaman after they believed he caused the illness and death of Hunter Jim, the last chief of the reservation. (His great granddaughter is the tribe’s current secretary). The four men were fined $1 each and sentenced to five years in San Quentin Prison after they struck a plea bargain and freely admitted they killed the shaman. They received a pardon in 1888.

Since then, the remote reservation with no cell service and just one local shop has struggled with both federal and state governments over timber and water rights, and resisted efforts by the state to limit its gaming. “It is a tribe that has really worked persistently and vigorously to sustain its sovereignty over a long period,” said Carole Goldberg, a UCLA law professor and co-author of Defining the Odds: The Tule River Tribe’s Struggle for Sovereignty in Three Centuries. “They are very committed to their community and their way of life.”

The reservation relies heavily on the Eagle Mountain Casino for its revenues, and tribal members receive a per capita distribution each month, but the amount is minuscule. Most of the profit is invested in educational programs for the children, such as putting money aside for their college tuitions. “They have benefited from the opportunity to conduct tribal gaming, but location is everything and they are not located near a major highway or a major population center,” Goldberg said. “While the gaming has improved life on the reservation, it has not made them wealthy at all.”

The Tule River Tribe, as well as other California tribes, function under Public Law 280, which gives local law enforcement responsibility for handling crime on reservations, Goldberg explained. Although the tribe has a Department of Public Safety, which was established in 2006, it does not handle major crimes such as murder.

On Sunday, the church bells of Mater Dolorosa Catholic Church on the Tule River Reservation rang out five different times for the dead, a reservation tradition since 1933. “I am deeply saddened by this heartbreaking tragedy,” said Tribal Chairman Neil Peyron. “This has been one of the most horrific losses our community has ever faced.” The reservation plans to hold a candlelight vigil for the victims throughout the week.

In an issue statement, the tribal council said that Irene Celaya, Hector Celaya, and Bernard Moreno were not tribe members, but they did live on the reservation, and were community members. However, Celaya’s children and their uncle Francisco were enrolled members of the Tule River Tribe. Community members hope that the police investigation will shed some light on why Celaya, who reportedly loved his children, might have done such a terrible thing.

“Being he is deceased, we don’t get to question him on his motive,” said Sgt. Douglass. “Detectives are still investigating. They don’t just stop because the suspect has passed away.”

“The whole situation is very painful,” UCLA’s Goldberg said. “It is not a frequent occurrence in Indian country.”