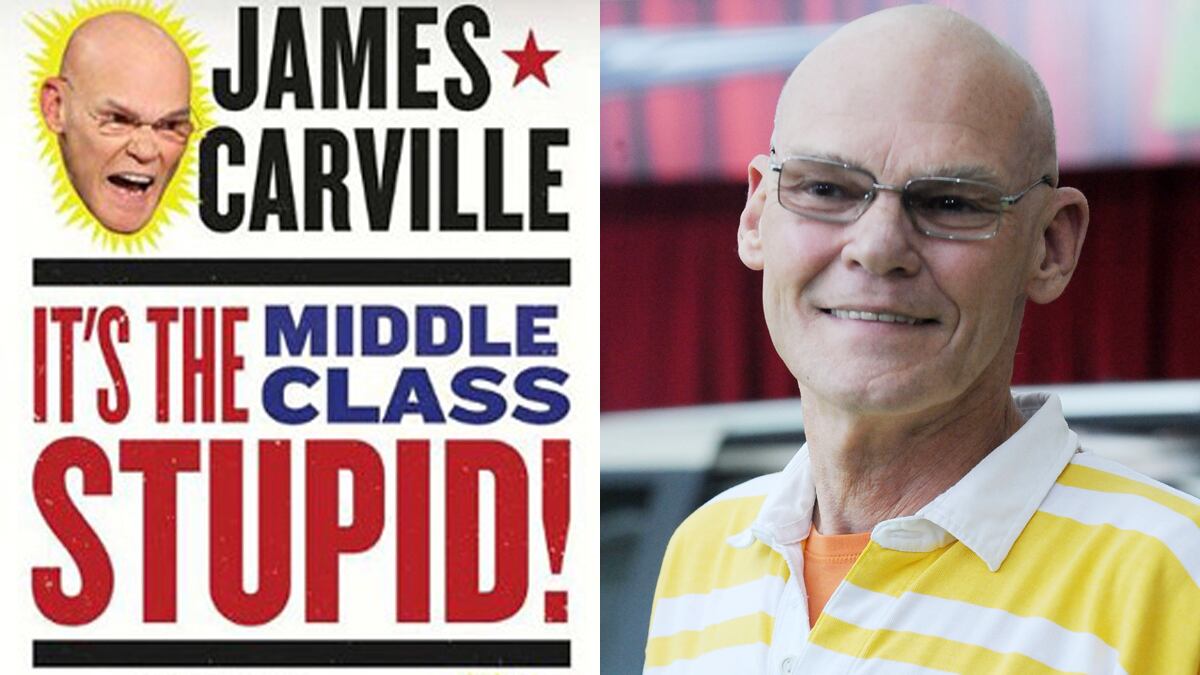

Bill Clinton loyalist James Carville—who has just co-written a book-length manifesto, It’s the Middle Class, Stupid!, with Clinton pollster Stan Greenberg—has a lot to say about a perverse political and media elite that snubs and otherwise disses America’s most vital yet distressed demographic.

But first, and just as important, he has a lot to say about the passing of Andy Griffith last week at age 86.

“I met him a couple of times during the 1992 campaign,” says Carville, who happens to head up the Washington chapter of The Andy Griffith Show Rerun Watchers Club, nicknamed “The Governor’s Parking Ticket Chapter” after an episode in which Mayberry, N.C., Deputy Sheriff Barney Fife (played by the late Don Knotts) slaps a parking ticket on the governor’s car and hilarity ensues. “Andy gave some money. He wasn’t as political as some of the other Hollywood people, but he was actually a pretty good Democrat.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“Andy Griffith [which in Ragin’ Cajun is pronounced “Griffin”] was probably one of the three or five most influential comedies in the history of television,” says Carville, who has been a pop-culture celebrity for the past two decades on the strength of his theatrical eccentricity, peculiar accent, and brilliant strategic advice to the winner of the 1992 presidential election. “Andy was a real accomplished guy,” Carville tells me. “But he never beat anybody up or got in a fight in a nightclub or that shit that’s so typical of what you see. The few times I met him, he was pretty much the guy you think he is.”

Indeed, Griffith’s character, Sheriff Andy Taylor, was the personification of hardworking middle-class virtue, much as Mayberry was, as Carville puts it, “very sort of middle class ... As a kind of place, it was the way the country used to be. Mayberry had its faults. It wasn’t perfect. It was very prone to gossip.”

But the sitcom was also, in its way, surprisingly progressive. “It was very feminist,” Carville says. “Ellie [Andy’s girlfriend during the inaugural 1960–61 season] was the first professional woman on television. She was a pharmacist. She didn’t have a traditional female job. And she ran for the City Council ... The show was well written and well acted, and there were lessons in there, like when Opie kills the bird. And there was always a clever way for Andy to get something done without hurting people’s feelings.”

In other words, it was worlds away from American politics circa 2012. In Carville’s view, the latter is an area of human endeavor that is slickly superficial, obsessed with short-term gain, and pigheadedly focused on the wrong problems—slavishly devoted to a cocktail-party agenda served up by East Coast elites who have little regard for real difficulties hurting ordinary people in the flyovers.

“I tell my students,” says Carville, who teaches a course in political practice at New Orleans’s Tulane University, “that the single most powerful thing that we have in this country—something that literally harbors no dissent and no questioning—is the all-powerful elite narrative.”

He elaborates: “Facts don’t get in the way of an elite narrative, OK? It’s like: ‘Obama hasn’t led on immigration.’ The truth of the matter is he put the bill up and it was filibustered by the Republicans. But you have to say that because that’s what they say at cocktail parties.”

What about the widely held critique that President Obama should have embraced the proposals of the presidentially appointed Bowles-Simpson deficit-reduction commission instead of running away from them? Carville, a card-carrying member of the Clinton wing of the Democratic Party, replies: “I’m not the biggest defender of the president. But [during last summer’s debt-ceiling crisis] he tried to offer the Republicans something that was even better than Simpson-Bowles, and they wouldn’t take his phone call. In other words, there’s nothing so powerful as an elite narrative.”

In yet another example, Carville cites the conventional wisdom—promulgated by elected officials, various nonprofit foundations, the Bowles-Simpson commission, and liberal and conservative think tanks alike—that long-term deficit reduction and entitlement reform are two most urgent issues confronting U.S. policymakers and politicians.

In their book—a mix of chatty dialogue between the authors, graphs, pie charts, and public-opinion surveys—Carville and Greenberg argue the opposite. Instead of worrying about mushrooming debt, the federal government should immediately spend hundreds of billions of additional dollars on repairing and enhancing the country’s infrastructure and other public projects to shore up the suffering middle class—which, after all, is America’s economic engine.

“You, being a card-carrying member of the American elite—” Carville asserts before I interrupt him with a sarcastic “thank you.”

“It’s OK, because most of the people I know are,” Carville responds. “From the elite standpoint, you think our entitlement problem is the central biggest problem that we face. If you wrote a book, it would be It’s the Entitlements, Stupid! But we’re saying that the central problem is the destruction and the deterioration of the American middle class.”

He goes on: “There’s no doubt that the middle class would get hammered if you had an unsustainable budget crisis. But the biggest driver of entitlement spending, the biggest impediment to staying in the middle class, is escalating health-care costs. Which don’t register on the radar screen of most elites.”

Carville argues that the problem is not Medicare and Medicaid, it’s the obscenely inflated health-care system, the most expensive on the planet, orchestrated by insurance companies and the medical establishment—a factor usually discounted in elite theorizing, he claims.

“If our health-care costs were the same as the second highest in the industrialized world, we would not even have a crisis,” he says. “But the elite answer is that we have to reduce the amount the government spends on health care. The middle-class answer is we have to reduce the amount the country spends on health care.”

As Arthur Miller’s character Linda Loman famously said about her defeated husband, Willy, attention must be paid! After all, since Bill Clinton left office, middle-class families have lost 40 percent of their net worth, and wages have been declining or flat since the 1970s, while the top 1 percent has continued to accumulate wealth at lightning speed while seeing its income tripled.

“I think we should embrace the deterioration of the middle class as the single biggest problem that the United States faces,” Carville says. “Bigger than the long-range entitlement crisis. Bigger than the short-term financial crisis. Bigger than terrorism. Bigger than anything.”

It’s a rare focus group on the middle class, Carville says, where at least one of the participants doesn’t break down in tears in the midst of recounting their family’s economic ordeals.

“Our point is that if you put this issue front and center,” Carville says, “and you ask: where is the National Commission on the Middle Class? Where is the Princeton Institute for the Study of the American Middle Class? You might end up with a different result.”

As for Obama, Carville believes the president made an error in early 2009 by compromising on too small a government spending package and “that instead of selling the stimulus as a short-term fix for the economy, it would have been better if we had a sold it as a way to rebuild the middle class ... The branding of the Democratic Party should be that we are the party of the great American middle class.”

Obama “is getting more focused now, and he’s I don’t know how many times better than Romney on this question, but to do better than Romney is not [difficult]. Romney doesn’t even notice the middle class,” Carville says. “They deny it’s a problem. They just say ‘Everybody’s got cellphones, and why are you worried about it?’ They’re kind of the economic equivalent of birthers.”

The irony of all of the above, of course, is that Carville, one of the 1 percent, lives a pretty fabulous lifestyle consorting with the very Washington–New York–Hollywood elites he likes to decry. He’s famously married to, and shares two daughters with, Republican political operative, pundit, and book publisher Mary Matalin, a Mitt Romney supporter.

“What am I supposed to do, get a divorce?” Carville demands. “What, I’m not supposed to talk to my sister? I have a bunch of sisters, some agree with me, some disagree. I go to a dinner party and God knows who I see at dinner parties. What am I supposed to do, shun people?”

He adds: “You know I’ve been part of that [the elites] for the last 20 years, and I just finished writing this book. I never give myself credit for much, but I give myself credit for being in it for 20 years, and I’ve withstood the conventional wisdom.”