Jazz trumpeter, bandleader, and composer Terence Blanchard took up boxing in his 30s. He sees lots of parallels between boxing and jazz—the limited repertoire, the art to it, and improvising.

When Blanchard’s boxing trainer, former heavyweight champion Michael Bentt, told him about Emile Griffith, Blanchard was captivated by the story of the world welter- and middleweight champion who accidentally killed an opponent, Benny Paret, in the ring during a 1962 match, hitting him 17 times in the last round. Paret went to the hospital in a coma and died 10 days later.

The incident haunted Griffith, becoming a defining moment in his career. Griffith was gay, and at the weigh-in before the fight, Paret had taunted him, calling him a “maricon,” a derogatory Spanish term, similar to “faggot.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Griffith was from the U. S. Virgin Islands, and already struggled as a black man in American, Blanchard said—and along with that he faced the discrimination that loving men brought.

“I remember when I won my first Grammy, when they called my name, I looked to my wife and gave her a hug,” Blanchard said. “Emile couldn’t celebrate openly with someone he loved, and we should all be well past all that kind of intolerance.”

Wanting to learn more about Griffith, Blanchard read Ron Ross’ biography of him, Nine... Ten... and Out! He found a quote that struck him: “I keep thinking how strange it is ... I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. However, I love a man and to so many people this is an unforgivable sin.”

To Blanchard, this was tragically still relevant. So when the Opera Theater of Saint Louis called wanting him to write an opera—a first for the man who’s done scores for about 50 movies, including all of Spike Lee’s since 1991’s Jungle Fever—he had a subject in mind. They suggested something about Hurricane Katrina, but Blanchard had a different idea—something based on Griffith’s life.

He wrote Champion: An Opera in Jazz, which has its West Coast premiere at the SF JAZZ Center (where Blanchard is a resident artistic director) on Feb. 19, staged with a jazz trio, orchestra, and gospel chorus.

Randall Kline, the executive artistic director of SF JAZZ, had heard of Griffith. When he was a little boy, he and his brothers used to watch Griffith box on TV. Kline didn’t see the fight where Paret was killed, but he remembers hearing about it.

“He was world famous,” Kline said about Griffith. “It was national news. I didn’t know the full story—that at the weigh-in, he’d called him a faggot.”

Watching Griffith box made a big impression on him, Kline says.

“He was a beautiful guy, this elegant human being. There was this magnetic thing about him,” Kline said. “It’s a great tragedy that this elegant man who was part of the toughest aspect of our society—a world champion boxer—couldn’t be himself. He was a black man and an underdog, and then he was hanging out in gay bars and getting beaten up by thugs.”

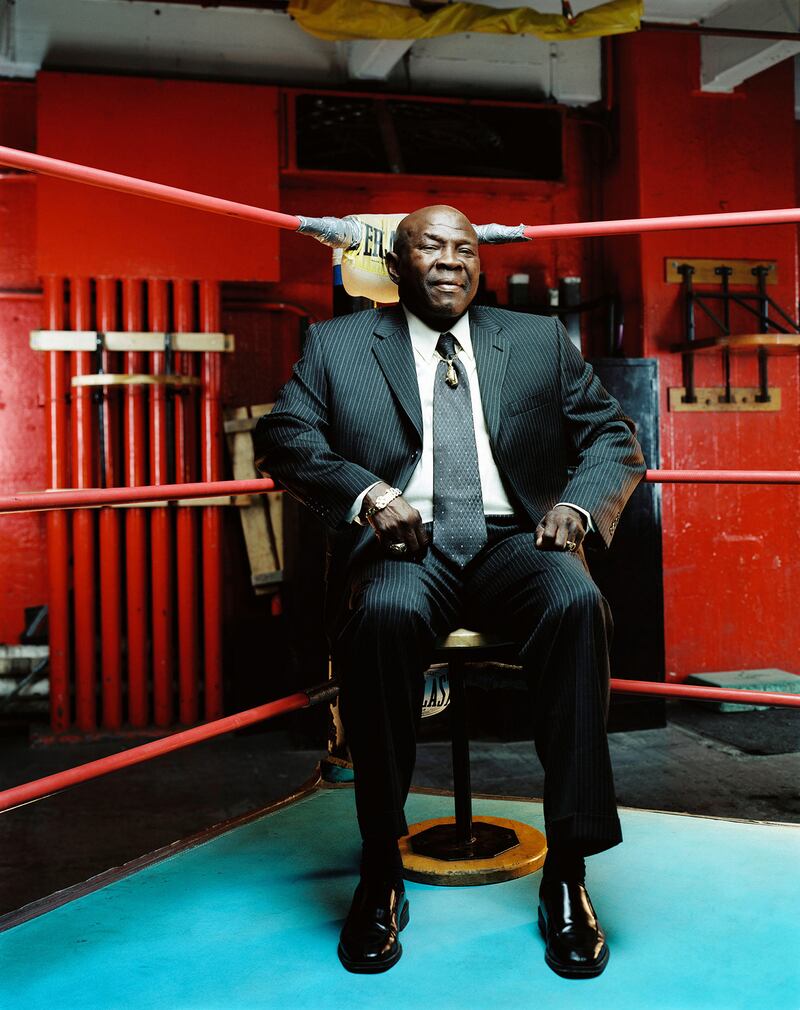

Bentt, the boxer who trained Blanchard, says that Caribbean society is particularly macho and homophobic. Bentt, whose parents were from Jamaica, says when he heard about Griffith, it was in the context of “that fucking faggot.” He met him at Gleason’s Gym in New York, and said Griffith was helpful and open, offering him tips on fighting. Bentt came to admire Griffith for living his life his own way.

“The older I got, the more I was like, ‘That was really bold of this guy, man,’” he said. “I thought that was impressive and very courageous. He was black and an immigrant, so he was already an outsider. He accepted his attraction to men. I think it fueled him—boxers fight because they’re victims at some point in their lives. Emile was highly sensitive, and to have caused the death of another fighter—that haunted him the rest of his life.”

Griffith dreamed about Paret and would see an image of him in the mirror when he was shaving, Ross, a former boxer who wrote Griffith’s biography, said. Ross added that Griffith was turned away when he tried to visit Paret in the hospital.

Ross, who lived near Griffith on Long Island, says when he was writing the book, the two became good friends, with Griffith coming by his house and playing cards with his children, now grown.

Ross was also at the ’62 bout at Madison Square Garden when Griffith cornered Paret in the last round, hitting him until he slid down the ropes onto the floor, and he remembers it well.

“It was a terrible scene to observe,” he said. “I knew Benny was badly hurt, and to see him on the canvas like that was awful. The crowd was shocked, waiting to see if Benny was going to get up. They went silent. It really affected boxing. They talked about banning it for a while, and they kept it off TV for a long time after that.”

Griffith told Ross that he meant to knock Paret out, but never wanted to permanently hurt him. After Paret’s death, Griffith stopped fighting for a while. Receiving letters from others, such as truck drivers, who had accidentally killed someone, helped him enormously, and he went back to the sport, retiring in 1977.

Nicole Paiement, the artistic director of Opera Parallèle, which is collaborating on Champion with SF JAZZ, says Griffith’s story is perfect for opera, where it can enthrall audiences, and not intimidate them with the musical language.

For Blanchard, Griffith’s story is universal because it deals with being misunderstood and judged.

“Look at the young African American men getting killed by the police, judged solely on the color of their skin,” he said. “Look at women still being judged on their gender and dealing with a pay equity gap.”

Champion examines how human beings treat each other, says Bentt, who is now an actor.

“It’s poignant material and relevant because it still happens—we get labeled every day, and told what we should hate and love,” he said. “Emile had to fight that journey by himself. Judgment makes us feel better about ourselves, and that’s what the opera gets across so brilliantly. It points a finger at us.”