As a libertarian, I’m always slow to tell people what they should do. But if you care about politics and the ultimately far more powerful cultural direction of these United States, the new book by Daniel Schulman, Sons of Wichita: How the Koch Brothers Became America’s Most Powerful and Private Dynasty, is mandatory reading.

Written by a senior editor for the lefty magazine Mother Jones, the book is hugely revelatory, though not in a way that will please or flatter the conspiracy theories of Democrats, liberals, and progressives who vilify the Kansas-raised billionaires Charles and David Koch for fun and profit. Sons of Wichita chronicles the post-World War II transformation of a mid-size oil-and-ranching family business into the second-largest privately held company in the United States. From a straight business angle, it’s riveting and illuminating not just about how Koch Industries—makers of “energy, food, building and agricultural materials…and…products [that] intersect every day with the lives of every American”—evolved over the past 60 years but also how the larger U.S. economy changed and globalized.

But what’s far more interesting—and important to contemporary America—is the way in which Schulman documents the absolute seriousness with which Charles and David have always taken specifically libertarian ideas and their signal role in helping to create a “freedom movement” to counter what they have long seen as a more effective mix of educational, activist, and intellectual groups on the broadly defined left. By treating the Koch brothers’ activities in critical but fair terms, Sons of Wichita points to what I like to think of as Libertarianism 3.0, a political and cultural development that, if successful, will not only frustrate the left but fundamentally alter the right by creating fusion between forces of social tolerance and fiscal responsibility.

“One misconception that’s out there,” Schulman told me in an interview, “is that these guys are merely out there to line their pockets. If you look at their beliefs in a consistent framework, Charles Koch has been talking about a lot of this [libertarian] stuff since the 1960s and 1970s. This didn’t just happen during the Obama era. And if you look at it that way, you have to start to see these guys as outside the political villain-robber baron caricature.”

In the interests of disclosure, I should note that David Koch is a trustee of Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes Reason.com and Reason.tv, of which I’m editor in chief. Back in 1993, I received a fellowship for around $3,500 from the Institute for Humane Studies, of which Charles Koch is a major benefactor; the grant helped me complete my Ph.D. in American literature at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Imagine, if you will, a country in which government at every level spends less money and does fewer things (but does them more effectively), doles out fewer perks to special interests (from Wall Street banks to sports teams to homeowners), regulates fewer things across the board, engages in fewer wars and less domestic spying, and embraces things such as gay marriage, drug legalization, and immigration. If surveys showing record levels of Americans are worried that government is too powerful are accurate, libertarianism may well be on its way to becoming the new civic religion. That’s partly out of necessity (no country can spend money it doesn’t have forever) and partly out of intellectual shifts borne out of argumentation and world events.

In a recent piece for The Washington Post, Schulman reminds readers that while the Koch brothers remain staunch opponents of Obamacare and government spending, “they are at odds with the conservative mainstream” and “were no fans of the Iraq war.” As a young man, Charles was booted from the John Birch Society (which his father had helped to found) after publishing an anti-Vietnam War newspaper ad, and David told Politico of his support for gay marriage from the floor of the 2012 Republican National Convention. In the past year, the Charles Koch Institute cosponsored events with Buzzfeed about immigration reform (which angered many on the right) and with Mediaite about criminal justice reform.

The libertarian or “freedom movement” is a loose and baggy monster that includes the Libertarian Party; Ron Paul fans of all ages; Reason magazine subscribers; glad-handers at Cato Institute’s free-lunch events in D.C.; Ayn Rand obsessives and Robert Heinlein buffs; the curmudgeons at Antiwar.com; most of the economics department at George Mason University and up to about one-third of all Nobel Prize winners in economics; the beautiful mad dreamers at The Free State Project; and many others. As with all movements, there’s never a single nerve center or brain that controls everything. There’s an endless amount of infighting among factions and Schulman does an excellent and evenhanded job of reporting on all that. (For the definitive history of the movement, read my Reason colleague Brian Doherty’s Radicals for Capitalism.) On issues such as economic regulation, public spending, and taxes, libertarians tend to roll with the conservative right. On other issues—such as civil liberties, gay marriage, and drug legalization, we find more common ground with the progressive left.

Libertarianism 1.0 spans the 1960s and ’70s. It was a time of building groups and having arguments that hammered out what it meant to be a libertarian as opposed to a liberal who grokked free trade or a conservative who was against the warfare state. The Institute for Humane Studies was founded in the early 1960s by a former Cornell economics professor to nurture libertarian-minded college students and would-be academics. The founder, F.A. Harper, was an important intellectual mentor to Charles Koch, who became a major donor to the group. Reason magazine started publishing in 1968, created by a Boston University student who disliked cops and hippies in equal measure and wanted to create a conversation pit for libertarian ideas, news, and commentary. The Age of Aquarius didn’t end before The New York Times magazine declared libertarianism to be “the new right credo” and the next big thing among students in a cover story co-written by future Wired magazine founder Louis Rossetto. The article described John Kennedy and Richard Nixon as differing types of statist “reactionaries.”

The always-rumbling fault line between equally anti-communist conservatives and libertarians in Bill Buckley’s student group, Young Americans for Freedom, ruptured irrevocably over the Vietnam War at the 1969 YAF national convention (PDF), when the libertarian protesters burned their draft cards and were expelled as “lazy fairies,” a play on laissez-faire. That was one of the events that gave rise to the Libertarian Party in 1971, whose platform called not only for an end to gender discrimination but equality for gays (virtually unthinkable among Democrats and Republicans at the time).

In 1977, Charles Koch was one of the co-founders of the Cato Institute—and, as Schulman puts it, “the organization’s wallet.” In a 1978 issue of Libertarian Review, Schulman writes, Charles “decried corporate leaders who preached ‘freedom in voluntary economic activities,’ but simultaneously called for ‘the full force of the law against voluntary sexual or other personal activities.’” He didn’t have patience for businessmen who railed against welfare for the poor while lobbying for subsidies and protectionist policies for their own bottom lines, either.

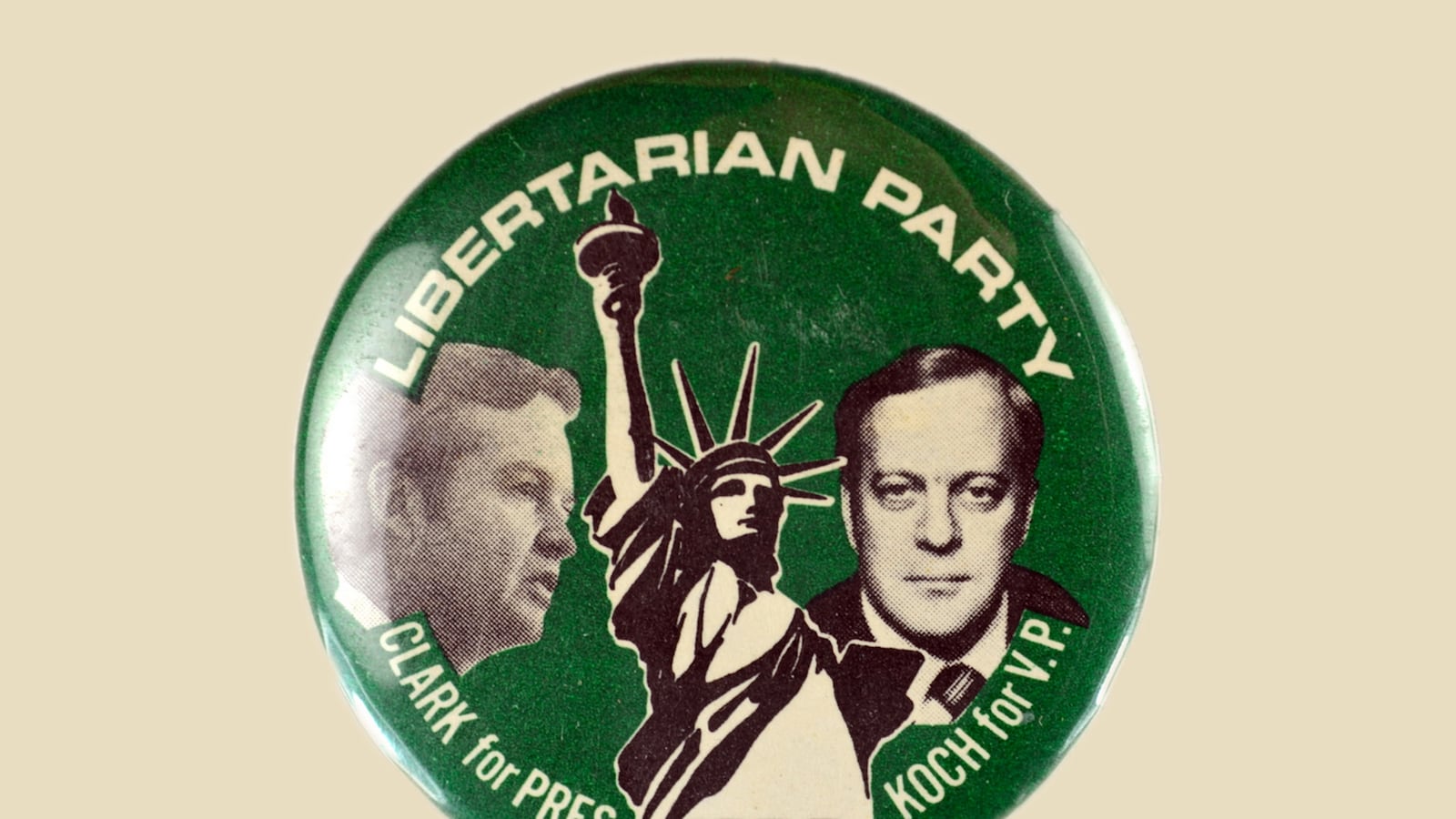

In 1980, David Koch ran for vice president on the Libertarian Party ticket, which pulled 1 percent of the popular vote on a platform that assailed Carter and Reagan in equal measures while calling for massively lower taxes and spending, the legalization of drugs and prostitution, and the abolition of virtually all government programs and agencies, including the FDA and the EPA along with the CIA and FBI. The campaign was explicitly informational and intended to preach the gospel of less interference in the boardroom and the bedroom. “The ideas are so persuasive,” David said at the start of the campaign, “that once people hear about them they will be willing to accept them.” Schulman notes that David listed “his vice presidential candidacy years later under ‘proudest achievement’ on an MIT alumni questionnaire.”

Libertarianism 2.0 covers the past 30 years or so. By the early 1980s, the libertarian movement had established a distinct ideological identity, albeit one often ignored or put down by an older, square conservative movement that still considered libertarianism as a punky younger brother. On the left, libertarians were routinely dismissed as “Republicans who smoke pot.” As they gained strength and acknowledgement, libertarians started more actively engaging in mainstream politics, especially by working within the Republican Party, which at least espoused similar rhetoric about limiting the size, scope, and spending of government (that Reagan and the GOP did nothing of the sort remains a sore point for libertarians). Bill Clinton’s tax hikes, his attempt to put government-accessible “backdoors” into all computer and telecom equipment, his bid to regulate the fledgling Internet via The Communications Decency Act, and of course his proposed health-care plan in the early 1990s galvanized many libertarians against him. The occasional pro-freedom and futurist pronouncements by characters such as Newt Gingrich (who graced the cover of Wired in 1995 with the tagline “Friend and Foe”) seemed to offer serious common ground between libertarians and the Republican Party.

By century’s end, Al Gore’s increasingly strident environmentalism had for libertarians fully trumped his full-throated early ’90s defense of free trade while debating H. Ross Perot on Larry King Live. His leading role in giving his wife Tipper’s Parents Music Resource Council a platform to push music labeling in Senate hearings was a real problem too. By contrast, George W. Bush’s low-tax record in Texas and belief in a “humble” foreign policy sounded pretty good.

Yet Bush’s subsequent record on spending, civil liberties, foreign policy, and bailouts underscored the longstanding libertarian conviction that most differences between the two major parties were cosmetic. Not only did Bush—who had six years with a Republican House and Senate—grow federal spending by more than 50 percent in real dollars, he massively increased the regulatory state like no one else had since the days of Richard Nixon. Consider this damning January 2009 summary of his record compiled by economist Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center (a Koch-supported outfit, by the way):

The Bush team has spent more taxpayer money on issuing and enforcing regulations than any previous administration in U.S. history. Between fiscal year 2001 and fiscal year 2009, outlays on regulatory activities, adjusted for inflation, increased from $26.4 billion to an estimated $42.7 billion, or 62 percent. By contrast, President Clinton increased real spending on regulatory activities by 31 percent, from $20.1 billion in 1993 to $26.4 billion in 2001.

About the only thing that could seem worse to libertarians was the prospect of a President Obama who not only readily signed on to Bush’s TARP and auto bailouts but pledged to expand them, spend hundreds of billions of additional dollars on “stimulus,” and then top it off with a nationalized health-care plan.

As Schulman writes, the Kochs already started organizing invite-only, heavily attacked (by the progressive blogosphere), and fully compliant-with-campaign-law meetings to raise money for political action starting in the Bush years, with an eye toward funding candidates and causes that would push for freer markets and less regulation, defeat Obama, sink his health-care reform plan, and push back against other aspects of the progressive Democratic economic and regulatory agenda.

Despite some electoral successes, these efforts have largely come a cropper, especially with the defeat of Mitt Romney in 2012. Schulman writes that although David Koch ultimately became a major supporter of Romney, he withheld his “formal support” until New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie declined to run and Romney had dispatched his GOP rivals. He quotes a friend of Charles saying, “Charles loved the governor from New Mexico, Gary Johnson,” who ran on the Libertarian ticket (and pulled more than 1 million votes and around 1 percent of the popular vote, the party’s best showing since the 1980 ticket that featured David).

The Kochs’ political network spent more than $400 million trying to unseat Barack Obama—the weakest, most vulnerable incumbent president in decades to win re-election. Their failure to do so didn’t just create a dark night of the soul for the Republican Party, which pledged to do an official post-mortem and organizational reboot. It also, says Schulman, has energized the Koch brothers and their political operation to figure out where they failed to connect with the American people. And unlike the GOP, whose dedication to fundamental change went missing the minute Obama’s popularity dipped after his second term began, the Kochs, Schulman told me, “really do learn from their mistakes. What you see right now is kind of the overhaul of their political operation.”

Which brings me to Libertarianism 3.0. The first iteration of the modern libertarian movement was focused on figuring out who we were and what sorts of institutions and outreach were necessary for the movement. The second was about working within existing power structures, sometimes even to the point of keeping mum on matters of serious disagreement. I’d argue that Libertarianism 3.0 will be a phase in which libertarians pursue two parallel political paths.

The first is outlined in The Declaration of Independents, the book I co-authored with Matt Welch: As increasing numbers of Americans flee affiliation with either major party, libertarians and others will form ad hoc coalitions that focus on specific issues and then disband after a threat has been stared down. That happened in 2012, when a rag-tag group of people from all over the political spectrum teamed up to defeat The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and its Senate counterpart The Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA). Ralph Nader is calling for something similar in his new book, Unstoppable: The Emerging Right-Left Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State. In a recent interview, Nader—no fan of major parties, he—told me that libertarians and progressives could get a “hell of a lot done if they would band together on specific issues” such as cronyism and corporate subsidies. (The problem, he said, is that “everyone wants to win every argument on the things they disagree about.”)

The second strategy is relevant to those trying to work within the Republican Party (and possibly the Democratic Party in time). They will start insisting that their economic and social views not only get taken seriously but start driving the agenda. That’s the strategy that Matt Kibbe, head of FreedomWorks, champions in books such as 2011’s Hostile Takeover and this year’s Don’t Hurt People and Take Their Stuff.

It may well be the path that the Kochs are pursuing. There are signs that this is already happening. As Schulman writes, the Republican establishment has always had reservations about the Kochs, “who often aligned with the Republicans on free-market issues and downsizing government… [but] Republicans [couldn’t] count on the Kochs to fall in step on issues such as immigration, civil liberties, or defense, where they held more liberal views. The brothers and their company also opposed subsidies across the board, a position GOP members didn’t always share. ‘The Republicans don’t trust us,’ said one Koch political operative.”

But at this point, the GOP may need the Kochs—and the libertarian vote—more than they need the GOP. You don’t have to be a savvy businessman to know that spending $400 million to lose a very winnable presidential election isn’t a good use of money. If the Republican Party refuses to take libertarian ideas seriously, there’s really nothing in it for libertarians to stick around.

There remains a serious question of whether or how far the Kochs will push for unambiguously libertarian positions as the price for their support. On economic issues, that will be daunting enough when you think about the massive growth in the size, scope, and spending of government under George W. Bush and a Republican Congress. Even now, the House Republican budget plan calls for increasing annual spending over the next decade from around $3.6 trillion to $5 trillion.

When it comes to the social issues the GOP refuses to stop talking about despite declining levels of support among voters, the Kochs’ record of direct activism has never been strong. During the Libertarianism 2.0 phase, they supported libertarian groups such as Reason Foundation and Cato that call for drug legalization, marriage equality, open borders, and the like, but there’s no question that they focused most of their literal and figurative political capital on economic issues that caused less stress among establishment Republicans.

“The brothers have traditionally avoided bankrolling advocacy on controversial social issues,” Schulman writes in his Post op-ed, “but they would certainly throw a curveball to their opponents on the left (not to mention their supporters on the right) by actively backing the causes of marriage equality or reproductive rights.”

The standard GOP response to unapologetic libertarianism is fear and dismissal: It’s too whacked out, too radical, too scary. Yet the only branch of the Republican Party that isn’t dead and withered is precisely the libertarian one. Retired Rep. Ron Paul (who ran for president on the Libertarian Party ticket in 1988) packed college campuses with young kids and retirees with a vision of limited government, fed audits, and restrained foreign policy. If he fired up an enthusiasm that was never fully reflected in his vote totals, he also inspired a new generation of candidates and activists who want to be part of a major party. Whose heart flutters at the sight of John Boehner or Eric Cantor? While not necessarily doctrinaire libertarians, characters such as Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), Rep. Justin Amash (R-Mich.), and Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) are not only pushing for defense spending and the NSA to be put on the chopping block, they are increasingly pushing for marriage and drug issues to be settled at the state level. Paul is consistently at the top of polls for 2016 presidential contenders.

Consider, too, the re-election campaign of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). McConnell is not running for another term like he used to. In 2008, McConnell ran ads touting the billions of dollars of pork he had brought home to Kentucky over the years. “That would never fly today,” the former head of the Tea Party Express told Business Insider. In 2010, McConnell did everything he could to keep Rand Paul from becoming the junior senator from the Bluegrass State (Paul defeated McConnell’s pick in the GOP primary). This time, McConnell worked overtime to secure an early endorsement from Paul. He even hired Paul’s former campaign manager and supported a state bill championed by Rand Paul and Thomas Massie that legalized hemp production.

In a poll from last fall (the most recent on the topic), Gallup found that “a majority, 53 percent, favor less government involvement in addressing the nation’s problems in order to reduce taxes, while 13 percent favor more government involvement to address the nation’s problems, and higher taxes.”

That’s a broadly libertarian point of view, and it’s certainly one that comports with Schulman’s analysis of the Koch brothers’ political vision. And it may speak to their influence on setting the terms of the conversation as well. In this passage, Schulman is writing specifically about Charles, but the idea applies to David as well: “He has arguably done more than anyone else to promote free-market economics and the broader ideology surrounding it. By mainstreaming libertarianism, he helped to change the way people think.”

Of course, it’s far from clear whether the Republican Party—or the larger country—will actually embrace anything resembling a principled libertarian approach not only to economic matters but to foreign policy, civil liberties, social issues, and more. Regardless of the outcome, though, one of the reasons—not the only one, to be sure—we’re even having this conversation is the Koch brothers. After eight disastrous years under George W. Bush and six (so far) under Barack Obama, it’s a conversation that’s been postponed long enough.