Summer as we know it was invented in 1923 by Gerald and Sarah Murphy, when they suggested to friends who owned a winter resort on the French Riviera—the Hotel du Cap—that it might be fun to keep the hotel open all year round.

Gerald painstakingly cleared seaweed from the beach—a place where no one had thought to lie down before—and soon enough the expat Americans’ many friends, including Pablo Picasso, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway were working on their tans and ogling each other in bathing suits, an activity they all called sunbathing.

The Murphys created summer, and their friend Fitzgerald created a special kind of summer novel—novels about rich people at the beach. Tender is the Night, dedicated to the Murphys, is the ur-novel about the love affair between the wealthy and the ocean. The look of heiress Nicole Diver’s pearls against her tanned skin has generated hundreds of other tanned heiresses. Every summer, there are a few in this special category—books in which families return to their summer homes on Nantucket or Martha’s Vineyard, in Vermont or in Maine, and problems ensue. These are people who spy on each other from boxwood hedges in their family compounds and obsess about weathervanes, golf club memberships, and beach rights. Their WASP’s nests have fanciful architecture and charming guesthouses and white hydrangea. They play tennis and sail catboats. They prep at Deerfield and go to Princeton or Harvard, where they end up at Ivy or Porcellian.

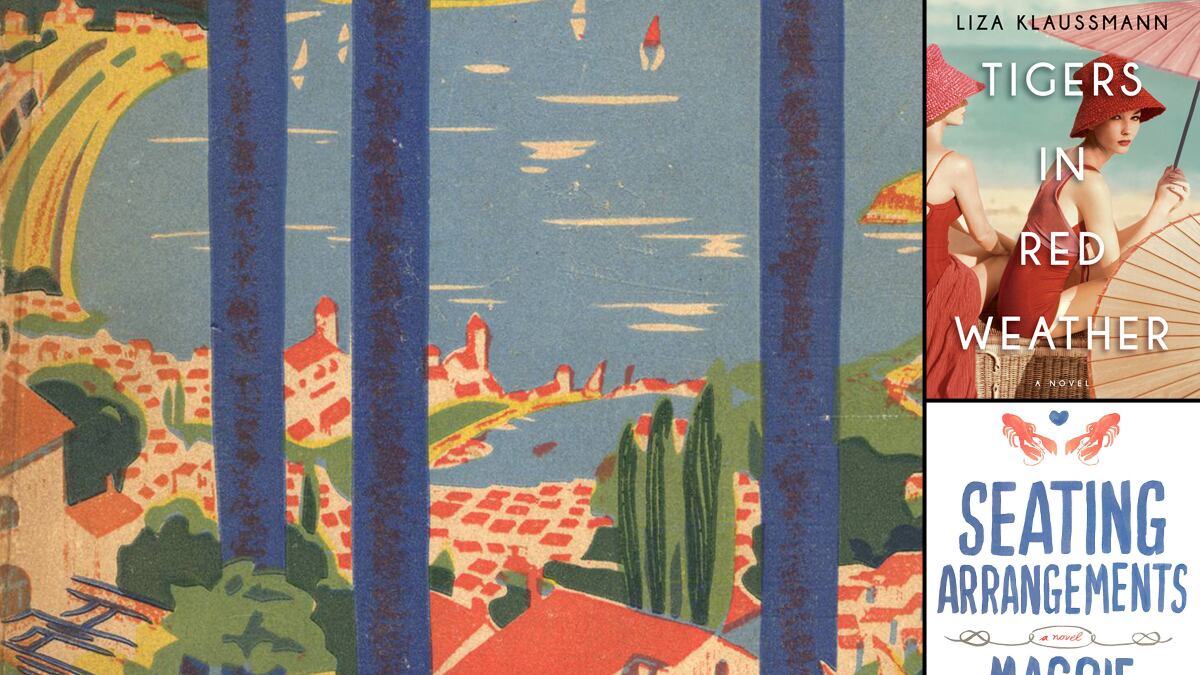

Maggie Shipstead’s Seating Arrangements is set during a three-day weekend wedding on a sandy New England island called Waskeke, much like the island of Nantucket. From the beginning there is suspense. Will Winn Van Meter the father of the bride end up having sex with Agatha, his daughter’s disheveled, sexy bridesmaid? Will his other daughter, the formerly pregnant Livia, recover from her recent break-up and find love? Will Daphne, the currently pregnant bride, have a tantrum? Van Meter is dying to get into the Pequod Club whose velvety greens he can see from his own widow’s walk—but something seems to be holding up his membership. He has been on the waiting list for three years. “They wanted to be aristocrats in a country that was not supposed to have an aristocracy,” thinks Daphne’s Deerfield friend Dominique on a bike ride to the lighthouse. “That was what Dominique could not understand: why devote so much energy to imitating a system that was supposed to be defunct. Any hereditary aristocracy was stupid, and Americans didn’t have the rules for theirs, not really. Lots of the kids Dominique knew at Deerfield came from families dedicated to perpetuating some moldy, half-understood code of conduct passed along by generations of imposters.”

Liza Klaussman has written a more complex, ambitious, and dramatic novel about the rich at the beach: three generations of a family which has always summered in the same compound on Martha’s Vineyard. Beginning with her literary title, Tigers in Red Weather, from the Wallace Stevens poem Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock, Klaussman unspools a story told from five points of view over two decades. Klaussman’s book is darker than Shipstead’s, there is disillusionment at all hours of the day, but it has all the same markers of wealth and class—the tennis matches and the boathouse and of course the martinis.

Like the characters in their stories, the two writers have impeccable credentials. Klaussman, a descendant of Herman Melville, worked for The New York Times, lived in Paris, and got her writing MA in London. Shipstead went to Harvard, got her writing degree at Iowa and is now a Stegner fellow at Stanford.

Both of these novels amply create what John Gardner called the “vivid, continuous dream” of fiction. Shipstead especially gets the details exactly right. Their writing is sharp, engaging, accomplished. Yet although these writers are the literary descendants of Fitzgerald, or even Cheever, their stories sometimes fail to become more than an accumulation of great details. Brilliantly readable, they tilt towards being readable the way the Preppy Handbook is readable, enjoyable in the same way that it is enjoyable to flip through the new Orvis catalogue.

“Fiction involves trace elements of magic; it works for reasons we can explain and also for reasons we can’t,” the novelist Michael Cunningham wrote recently. “If novels or short-story collections could be weighed strictly in terms of their components (fully developed characters, check; original voice, check; solidly crafted structure, check; serious theme, check) they might satisfy, but they would fail to enchant. A great work of fiction involves a certain frisson that occurs when its various components cohere and then ignite. The cause of the fire should, to some extent, elude the experts sent to investigate.”

Is it that great literature—Tender is the Night, for instance—is about failure, and that these novels ooze success—success of the writer if not of the characters? Is it that these novels—like Shades of Grey the most popular beach read of 2012—are really about not just about wealth but about the pornography of wealth, the glossy, wonderful things that wealth bestows—the silky clothes, the sunlit rooms where the light gleams on expensive woods, the parties, the trips?

Recently there has been a weird conflation of the product and product marketing in books, a coming together of the two least likely things in the world—serious writing and sales appeal. Some of my students seem as interested in writing query letters as they are in writing great sentences. Is it the proliferation of MFA programs? Is it the emphasis on book proposals rather than books? The growing importance of “blurbs” in which writing teachers endorse their own students?

Marketing is about success. Always be closing. Writing, great writing, often comes out of loneliness, humiliation, and other kinds of emotional malfunction. Always be open. My father couldn’t get into Harvard, couldn’t even get through high school, could barely get through life; Fitzgerald was another outsider, haunted by demons and drink, with a wife who famously told him she had to cheat on him because his penis was so small. These unhappy life stories led to some great fiction, fiction that can be read on a Nantucket beach, or in a bean- bag chair next to a sputtering air conditioner in a rented studio, or snuggled under blankets on a cold winter night—fiction for all seasons.