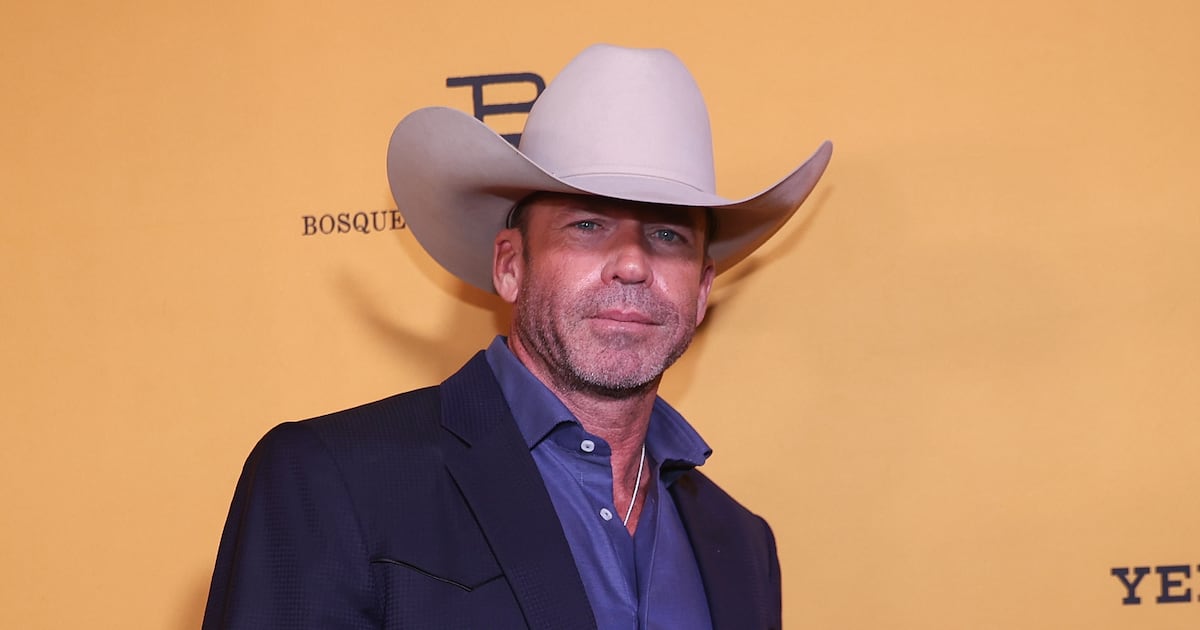

Tom Cruise is Hollywood’s last great movie star, and though his baby face is vanishing, he hasn’t stopped fighting Father Time, continuing to embark upon daredevil cinematic endeavors that reconfirm his eternal youthfulness.

Top Gun: Maverick (May 27) is an overt attempt at clinging to the past, a revisitation of the 1986 hit that propelled Cruise to the A-list stratosphere—and epitomized the decade’s hyper-flashy gung-ho spirit—through a combination of sonic-boom military showdowns, gauzy romance, Top 40 soundtrack singles, and sweaty homoerotic posturing. Yet more than that, director Joseph Kosinski’s sequel is a reaffirmation of its headliner’s peerless stardom and, with it, the full-throttle pleasures of yesteryear blockbusters that prized marquee personality and practical effects over weightless CGI spectacle. A nakedly nostalgic vehicle predicated on beloved IP and its leading man’s unflagging charisma, it’s a summer spectacular that proves that there’s still life left in the old ways, all while stoking, and satisfying, that familiar need for speed.

Cruise’s battle against aging reaches its apex with Top Gun: Maverick, which has been crafted as a shrine to his immortal manliness and the DIY action that’s now his stock-in-trade. “The future is coming, and you’re not in it… The end is inevitable, Maverick. Your kind is headed to extinction,” warns Rear Admiral (Ed Harris) to Cruise’s Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, who naturally replies, “Maybe so, sir. But not today.” Later, regarding a perilous undertaking, Maverick cautions his trainees, “Time is your greatest enemy.” The clock is ticking for Maverick, who thirty years into his distinguished career hasn’t risen above the rank of Captain due to a stubborn refusal to play by the rules. Such rebelliousness is both his gift and his curse, and that’s proven by an intro scene—“One last ride,” as Maverick tellingly dubs it—in which he disobeys orders and pilots a plane to Mach 10, a historic achievement he then surpasses and, in the process, sullies with a catastrophic wreck.

For his latest infraction, Maverick is shipped back to San Diego’s Top Gun academy, where he’s forced by unhappy-to-see-him Vice Admiral “Cyclone” (Jon Hamm) to train a squadron of ace newbies for a hazardous mission: infiltrate enemy territory and blow up an unsanctioned uranium enrichment site. The identity of these adversaries is kept deliberately vague by Ehren Kruger, Eric Warren Singer and Christopher McQuarrie’s script; as with its predecessor, the film keeps its politics abstract, the better to fixate on the breakneck exhilaration of its dogfights and the emotional plight of its protagonist. Maverick’s return to Top Gun is complicated by the fact that one of his recruits is Bradley “Rooster” Bradshaw (Miles Teller), son of his dearly departed buddy Goose (Anthony Edwards), whose demise still haunts him—and which has apparently compelled him to stymie Rooster’s career progress in an effort to protect him from meeting the same fate as his dad.

Top Gun: Maverick enthusiastically embraces its throwback nature, beginning with an orange-yellow sunrise sequence of silhouetted Naval officers going about their aircraft-carrier business to the sounds of Kenny Loggins’ “Danger Zone.” The sentimental shout-outs only escalate from there, be it via a Jerry Lee Lewis sing-along at the local watering hole, well-timed notes from Harold Faltermeyer’s original score, a respectful cameo from Val Kilmer (whose real-world ailments are incorporated into the story) or a shirtless beach football game played by a collection of glistening-torso Adonises. This contest is led, of course, by the 59-year-old Cruise, who as in a later scene in which he sneaks out of his new lover Penny’s (Jennifer Connelly) bedroom window, makes sure to foreground his own steadfast virility. There’s nothing subtle about any of these gestures, and also nothing resembling an ironic wink, with Cruise and the franchise sincerely and vigorously declaring their enduring relevance.

That may make Top Gun: Maverick sound hokey and self-absorbed, but Cruise and director Kosinski (Tron: Legacy, Oblivion) pull it off astoundingly well. Cruise’s magnetism remains unrivaled, and Kosinski pays reverent visual tribute to Tony Scott while simultaneously putting his own stamp on the rah-rah material. Kosinski places a premium on close-ups throughout, maintaining focus on his attractive characters and, consequently, turning the proceedings into a celebration of aesthetic beauty. His airborne showstoppers are similarly breathtaking, courtesy of both Claudio Miranda’s cinematography (which vacillates between harrowing cockpit views of pilots and grand vistas of the planes dwarfed by sprawling sky) and the fact that Cruise and company are actually flying these blistering war machines. There’s a weighty, propulsive realism to Kosinski’s centerpieces that, like Cruise’s performance, comes across as an exultant rebuke to the all-digital, all-the-time template that rules contemporary tentpoles.

There’s no narrative heft to Top Gun: Maverick; the stakes are simply whether Maverick’s indefatigable will—and belief in his (and, by extension, Cruise’s) push-the-limits ethos—can finally win over Rooster and help them bridge their differences. Everyone is playing a type, from Hamm as the scowling and disapproving boss, to Connelly as the understanding and smitten single mother who knows she has to let Maverick be Maverick, to Teller as the neophyte whose conservatism is a byproduct of his grief about his dad’s death, and who has to learn to eventually accept Maverick as his surrogate father. Understated it is not, and yet there’s a brash earnestness to this return engagement that’s hard to resist, especially given that Kosinski stages every fighter-jet skirmish with mounting suspense and thunderous intensity.

Top Gun: Maverick is an electric tribute to Scott’s 1986 classic, to ‘80s cinema in general, and to Cruise and his Dorian Gray smile. As such, it’s also something like a paean to an American political and artistic age that’s now in the rearview mirror, only kept visible and vibrant by those who believe in its value and vitality—especially in the face of a modern Marvel-dominated cine-universe defined by intangible sights and figures. The numerous Stars and Stripes seen blowing in the wind lend Kosinski’s follow-up a patriotism that, divorced from clearly delineated geopolitical specifics, seems itself wistful. That the film succeeds as well as it does, packing more excitement into its 131 minutes than most recent multiplex extravaganzas, speaks to Cruise and Kosinski’s excellence as well as the reliability of old-school craft—even if that triumph, ultimately, feels like the last gasp of a bygone era.