The thought that comes most easily to mind when watching Ezra Edelman’s nearly eight-hour documentary, O.J.: Made In America, is how impressive it is.

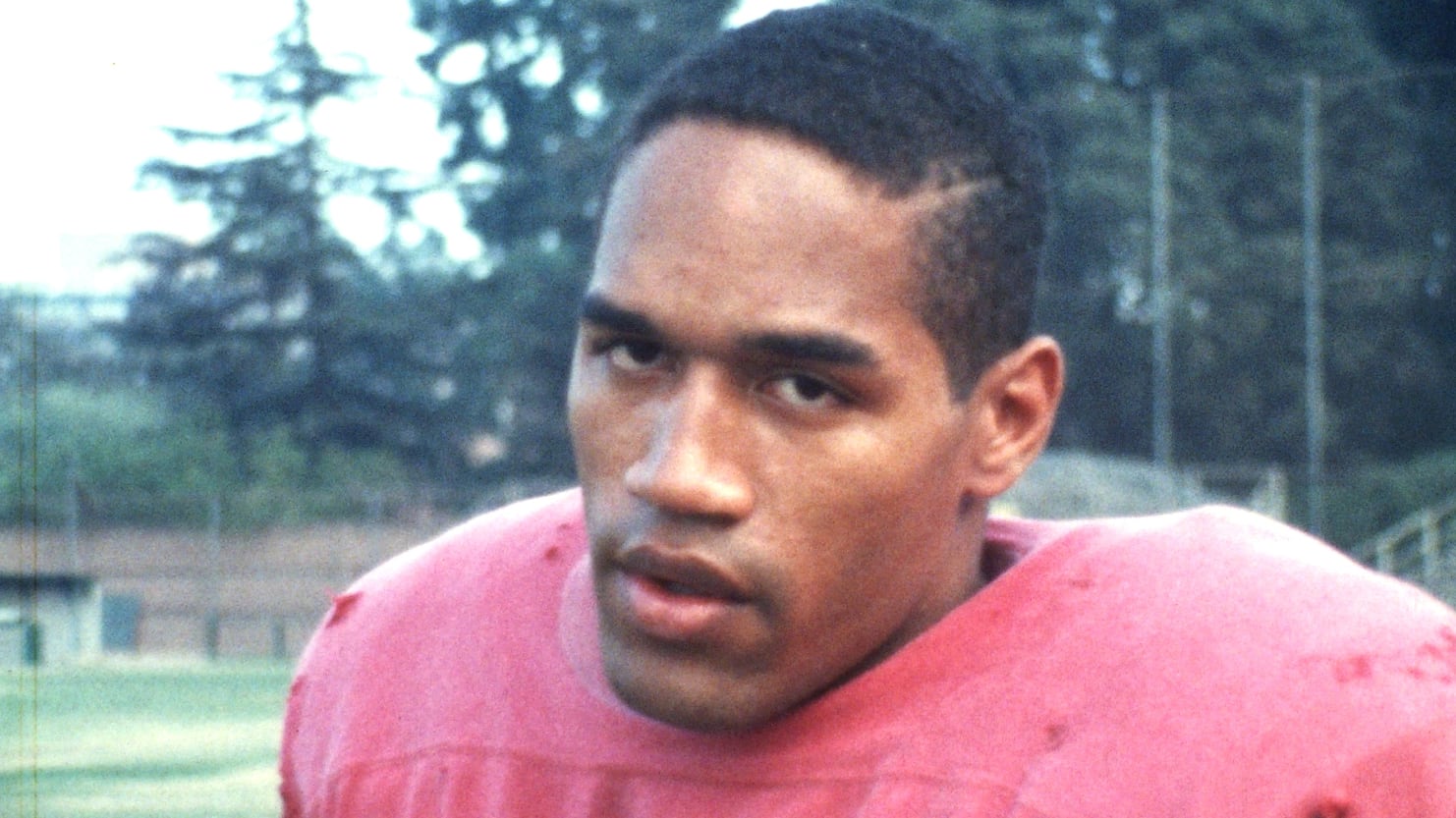

This is, it can easily be said, the most comprehensive portrait of Simpson’s life ever presented. For sheer amount of detail about his times, both before and after his 1994 murder trial, there really hasn’t been anything quite like it. In fact, with the exception of Muhammad Ali and Jackie Robinson, it’s doubtful that any American athlete has been afforded such scrutiny on film.

O.J.: Made in America is a labor of love, by which I do not mean love for the person at the center of its story. It seems impossible to me that any reasoning person can watch it and not clearly see that O.J. Simpson murdered his wife and her friend, Ron Goldman. And the fifth and final episode, the best in the five-part series if only because it covers O.J. after the acquittal with footage seen for the first time, reveals Simpson to be thoroughly venal and despicable.

ADVERTISEMENT

By labor of love I mean an attempt to fit the Simpson murder trial into the historical context of the horrendous treatment of blacks by the Los Angeles police force, exemplified but by no means limited to the 1992 police beating of Rodney King and the acquittal of the officers who assaulted him. If, like me, you wondered why black people all over the country cheered when O.J. got off, you won’t after you see this. It was, as one juror told Edelman, “Pay back for Rodney King” and, one can easily imagine, a lot of other wrongs.

But the truth is that “impressive” is what you say about something when you can’t actually say that you enjoyed it. The meticulous portrait of Simpson that is assembled from so many clips—home movies, football games, interviews, TV commercials, movies, trial coverage—are like a million pieces of a puzzle that, when they are finally assembled, add up to a picture of a perfect blank. Nowhere in his entire life does Simpson give the slightest indication of being anywhere nearly as interesting or intriguing as the black athletes who preceded him and paved the way for his enormous success.

In the final analysis, the only reason that we recall his name more than that of other great athletes who were as good or better is because of the murders and the sensational trial. So why are so many critics reacting to Made in America as if it was the second coming of The Sorrow and The Pity?—which, by the way, it exceeds in length by about three and a half hours. Made in America is nearly overwhelming, partly because of its length and detail, but also partly because it serves so perfectly as an expression of the psyche of liberals tortured by the murders, the trial, and the aftermath.

Are we really obsessed with O.J. Simpson, as some filmmakers think we are or should be? Between Edelman’s film and the recent TV miniseries, The People vs. O.J. Simpson, the current inmate of the Lovelock Correctional Facility in Nevada has now been given almost 16 hours of television time this year, surely 12 to 13 more hours than anyone would need to grasp the “real” O.J.

“If it were a book,” A.O. Scott wrote in the New York Times, “it could sit on the shelf alongside The Executioner’s Song by Norman Mailer and the great biographical works of Robert Caro.” Mailer and Caro? If Made in America were a book, it would it better alongside books like Darcy O’Brien’s The Hillside Strangler and Dark and Bloody Ground—that is, if those books were pumped up to four times their length.

Even more conflicted is New York magazine’s Will Leitch, who twists himself into Gordian knots trying to have it both ways. “The verdict,” he writes, “might have been bullshit. That doesn’t mean, in its own way, it wasn’t a grand victory.” By victory, Leitch presumably means that the entire process brought us to a greater understanding of racial politics in America. That really is bullshit.

Made in America, he says, “is full of footage of blacks and whites reacting to the verdict in diametrically opposite ways, and the genius [of the film] is that you absolutely understand why both sides were sort of right.” Except that when it was all over, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman weren’t “sort of” horribly murdered, they were horribly murdered.

For all of its exhaustive research and the craft with which it is assembled, O.J.: Made in America feels just a little too good about itself. Near the end, one of Simpson’s friends looks into the camera and proclaims, “It’s an American tragedy.” Edelman seems to let this stand as an epithet for the whole story.

But a tragedy for who? Does anyone really believe that there is a tragedy to O.J. Simpson’s story? There’s a bitter ugly irony, perhaps, but isn’t real tragedy made from the stuff of more elevated material? Surely the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were tragic, certainly for their families, but that doesn’t seem to be the point of view of a film that seems to encourage people to interpret O.J.’s acquittal as some sort of “grand victory.”

There’s one big gaping hole all through Made In America: sex. O.J.’s father had little to do with his son’s life and is practically unseen and completely unheard in the entire series. We’re told that his dad was gay, and the indication is that this caused O.J. huge embarrassment. (Jimmy Lee Simpson died of AIDS in 1986.) Episode two relates a scene where Simpson sees Nicole sitting in a restaurant next to a “homosexual man”—we have no idea how O.J. knows that—and “freaks out.” Clearly there are some larger issues at stake here concerning Simpson and sexual identity, but the subject is then dropped.

Also nearly absent from the series are the women in O.J.’s life—his mother, Eunice, sisters, daughters, and his first wife, Marguerite, whom he married in college. Made In America is supposed to be the story of Simpson’s life, and surely these women had much to do with shaping him. I do know that his mother, Eunice, tried to steer him in the right direction. In 1983, I flew to Buffalo for a profile on O.J. We spoke before the broadcast of Monday Night Football, and he told me that his mother, who knew Willie Mays, brought Mays to their apartment in the Portreo Hill Projects in San Francisco when O.J. was in high school to warn him to stay away from gangs.

God knows it would have been too much to ask Eunice, who died in 2001, to sit and talk about her son, and it appears no one did, since Edelman seems to have found no footage. But surely a relative could have been found, or at least a family friend, to fill in Eunice’s story and talk about her relationship with her son during his formative years and after the Nicole/Ron Goldman murders.

All the other women in Simpson’s life combined don’t get a fraction of the air time given to Nicole. Marguerite Whitley, who married O.J. during his junior year at Southern Cal and is the mother of three of his children (the youngest was almost two when she drowned in the family pool five months after they divorced) is as neglected by Edelman as she must have been by Simpson. However large she loomed in Simpson’s life, Made In America ignores her. She’s merely holding the stage until Nicole shows up, two years before Marguerite and O.J. divorced.

And what, ultimately, of Made in America’s treatment of Nicole herself? Much of the film’s focus is on race, which is understandable, but 21 years later there is still no one to speak up for Nicole Brown, who had long been abused “both physically and psychologically,” as someone in the film points out. (I’m not forgetting about the murder of Goldman, but he was murdered because he was with Nicole.)

There are photos after photos of the beautiful Nicole in everything from her wedding gown to a bikini, but no serious consideration of who she was and what she represented. Is there no one to consider why millions of American women weren’t united in their outrage over her death and the obvious injustice of O.J.’s acquittal? Couldn’t Edelman have found someone to ask if that acquittal might not have happened if the murders took place today?

There’s another large element missing from Edelman’s film, though he doesn’t seem to know it—fame. He captures a telling quote from Alan Dershowitz: “Because this is the most famous American ever charged with a murder, this won’t be business as usual.” Bingo. The real key to understanding the O.J. trial wasn’t race. Race is what the Simpson jurors, prodded by Johnny Cochran, reacted to, and it was what prompted hundreds of thousands of blacks in Los Angeles to take to the streets in near-euphoria when the verdict was announced. (We see one sign that says “We Love You O.J., Guilty or Not.”)

But tragedy isn’t what made the trial into a media frenzy in the first place—it was O.J.’s celebrity. Twenty years ago, Chris Rock, in one of his greatest routines, nailed it: “That shit wasn't about race...that shit was about fame. If O.J. wasn’t famous he’d be in jail right now. If O.J. drove a bus, he wouldn’t even be O.J. He’d be Orenthal, the bus driving murderer.”

OJ: Made in America premieres Saturday June 11 on ABC, 9PM EST.