The Trump administration is about to follow through on a major campaign promise—cracking down on Chinese trade practices—but the president’s nomination of a veteran industry lobbyist to lead the effort could quickly mire his trade agenda in ethics issues.

The administration previewed an aggressive package of protectionist trade policies last week, designed to crack down on market manipulation by China in particular. Just a few days earlier, President Donald Trump had nominated a top trade policy official to oversee an agenda that mirrors one he has pursued for years as a paid lobbyist for the steel industry.

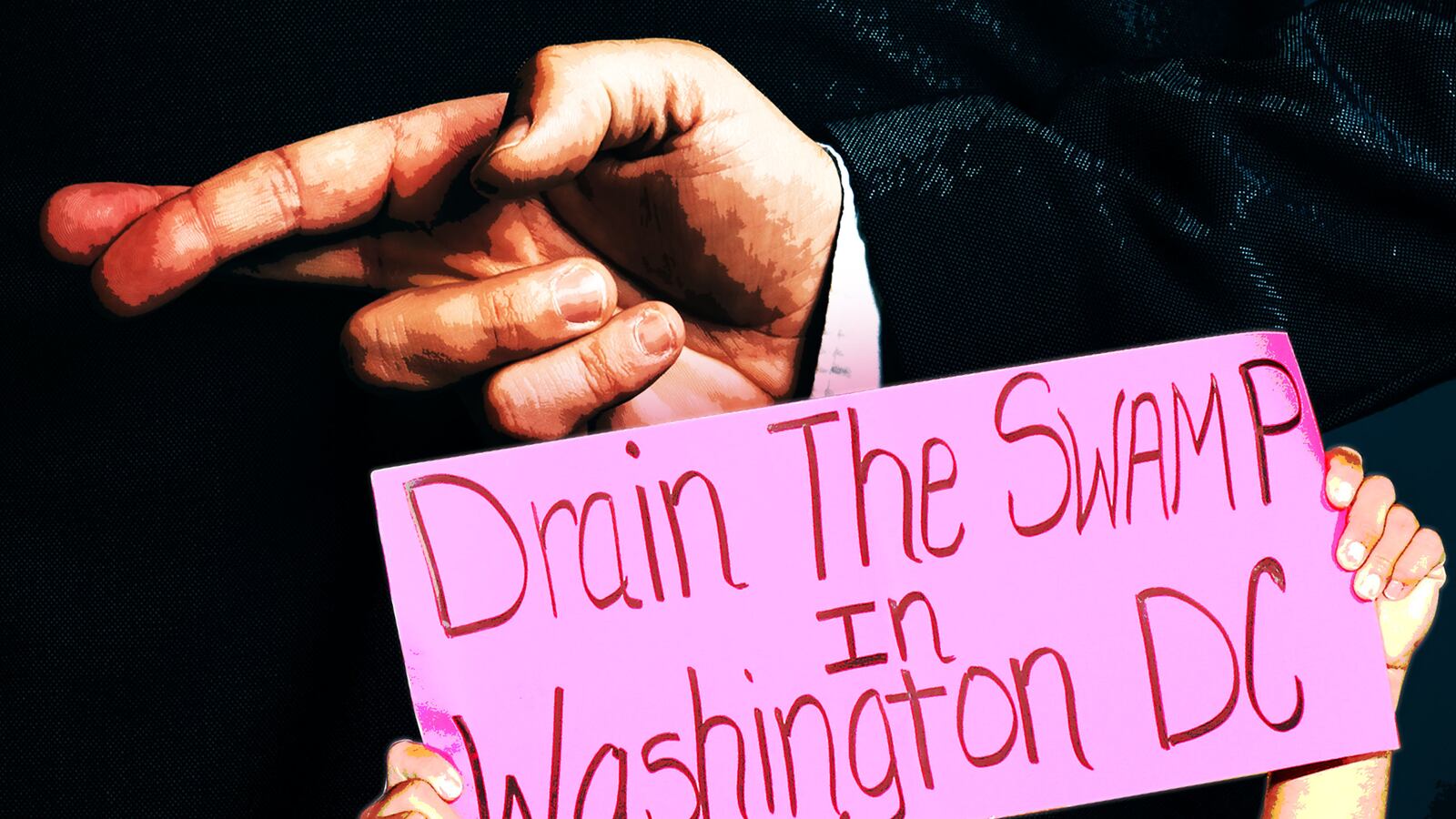

The confluence of interests sets up a potential clash with Trump’s own ethics rules, and illustrates how an administration ostensibly devoted to “draining the swamp” and reducing lobbyist influence on policymaking is melding its agenda with corporate advocacy efforts where those efforts align with the president’s priorities.

The administration isn’t draining the swamp so much as it is boosting its preferred special interests.

Trump is preparing a pair of executive orders designed to punish companies—Chinese companies in particular—that he blames for hollowing out American manufacturing. The details include ramping up enforcement of punitive tariffs on imports subsidized by foreign governments, a frequent practice among Chinese steel firms and one that the U.S. steel industry has fought for decades.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross previewed those policies on the White House’s website just a few days after Trump tapped steel industry lobbyist Gilbert Kaplan to be Ross’s top trade policy lieutenant. Kaplan worked for decades as a lobbyist and government official to advance the same policies that Trump’s executive orders seek to implement.

Kaplan is now vying to lead Commerce’s international trade division. If Kaplan is confirmed, he will lead the International Trade Administration, the federal body that oversees and enforces the precise types of import tariffs that the administration plans to employ in its efforts to crack down on alleged Chinese market manipulation.

There’s just one problem: The administration’s own ethics rules likely bar him from crafting and enforcing key portions of Trump’s executive orders, due to their overlap with the precise issues on which he was lobbying Congress and the administration until late last year.

With Kaplan helming those efforts, administration trade policy would be dictated at the highest levels by officials with longstanding ties to the steel industry. Ross himself is an industry veteran. He bought up distressed American steel companies in the early 2000s, consolidated them, and sold the conglomerate to Luxembourgian firm ArcelorMittal, now the world’s top steel manufacturer.

Kaplan, like Ross and Trump, is an unabashed promoter of the American steel industry. And that would be fine, had he not spent years on the industry’s payroll before seeking a post in an administration that ostensibly prohibits appointees from working on issues on which they recently lobbied.

Those rules were designed to limit Washington’s revolving door between regulators and the industries they regulate. Kaplan has passed through that revolving door more than once. Before his stint as a lobbyist, he oversaw steel industry policy in President Ronald Reagan’s Commerce Department, where he administered countervailing duties, or taxes on imports subsidized by foreign governments and sold domestically at below-market rates, a practice known as dumping.

Kaplan joined the law firm Hale & Dorr in 1990 and registered as a lobbyist in 1999 for companies including Bethlehem Steel, one of the firms Ross later bought up and sold to ArcelorMittal. More recently, at the firm King & Spalding, he lobbied on behalf of Chicago-based steel company Zekelman Industries.

From 2007 to present, Zekelman has paid King & Spalding more than $3.4 million to enlist Kaplan’s services in pressing Congress and federal agencies—including Commerce—to craft, implement, and enforce additional restrictions on Chinese steel imports. A year after Kaplan began, the Commerce Department imposed countervailing duties on Chinese competitors to Zekelman’s steel pipe products.

Kaplan’s nomination comes as Trump and Ross ramp up the administration’s protectionist agenda, an agenda that Kaplan was paid to promote for more than a decade. The policies that Kaplan will help administer at Commerce include one of Zekelman’s top regulatory priorities.

Ross pledged in his statement last week to go after what’s known as circumvention, or importers’ attempts to evade countervailing duties and other anti-dumping measures. Zekelman unsuccessfully filed an anti-circumvention petition late last year alleging evasion of the countervailing duties imposed on Chinese pipe imports in 2008.

The company might have better luck under Ross, who last week pledged ensure punitive tariffs are collected. It “makes no sense to expend the time and resources to get an affirmative ruling if you cannot then take the necessary action to punish and deter bad actors,” Ross said. “This will no longer occur.”

Lobbying disclosure forms show Kaplan’s work for Zekelman involved advocacy on general matters such as “international trade issues” and “China steel trade issues.” But he also lobbied on more specific issues, including legislation and regulation surrounding countervailing duties and other anti-dumping measures aimed at Chinese steel imports. Those policies are generally overseen by the arm of the Commerce Department that Kaplan is now vying to lead.

They are also pillars of the Trump administration’s emerging trade agenda. The president’s executive orders will reportedly step up efforts to enforce and collect countervailing duties and other anti-dumping measures. Ross emphasized those policies in his written remarks on the White House website last week.

That sets up a likely policy intersection with the specific issues on which Kaplan was lobbying until late last year. As a result, he could be barred from participating in major Commerce Department trade policy decisions unless the president decides to waive his own ethics rules to facilitate policymaking by an industry lobbyist.

Under ethics rules imposed by Trump’s predecessor, Kaplan would be barred from serving in the Commerce Department altogether. President Barack Obama’s White House decreed early in his administration that no one who had lobbied a federal agency in the past two years could seek or accept employment in that same agency.

Trump’s executive order omitted that provision entirely, even as it mirrored language in other parts of Obama’s ethics rules.

But Trump’s version does contain language that could prevent Kaplan from participating in major Commerce Department trade policy decisions on issues central to the president’s aggressive stance towards China.

Trump’s rules bar appointees from participating in “particular matters of general applicability” on which they lobbied in the past two years.

The language in legal interpretations of that prohibition can be murky, but it is generally interpreted to bar former lobbyists from working on specific regulations or legislation—such as import duties on a particular product—that affect an identifiable segment of the population that includes the people or organizations on which the appointee lobbied—say, U.S. steel companies.

The White House declined to comment on the record on the potential ethical pitfalls of Kaplan’s nomination. An official familiar with the ethics rules said Kaplan would be working with administration attorneys to navigate the application of ethics rules to his work at Commerce.

Lobbying disclosure filings, the official said, are “only a starting point as significant additional steps are taken to gain all relevant facts regarding compliance with the ethics pledge.” Where potential ethics issues arise, “a waiver may be requested and considered in the normal course.”

While it is within Trump’s authority to waive those rules where he sees fit, Washington’s revolving door is the precise type of insiderism that Trump vowed to combat.

“For those who control the levers of power in Washington, and for the global special interests they partner with, our campaign represents an existential threat,” Trump said late in the campaign.

The White House billed his January executive order implementing restrictions on employment by former lobbyists and lobbying by former administration officials as follow-through on the president’s repeated pledges to “drain the swamp” in Washington and upset the comfortable relationship between government officials and the special interests they regulate and oversee.

But Kaplan’s nomination highlights some gaping holes Trump’s ethics rules, and could be a test of how strictly the White House plans to enforce them against special interests that align with his policy priorities. A New York Times report last week revealed that a number of other lobbyists are running administration policy on issues on which they recently lobbied, in apparent violations of the ethics rules.

But the Times noted that there is no way to say definitively whether Trump has chosen to waive those rules to allow direct policymaking and regulation by lobbyists who are supposedly restricted in high-level administrative posts. The White House still will not make that information public in any comprehensive way.

A page on the White House’s website promises that waivers will be publicly disclosed as the information becomes available. But another page promising disclosure of visitors to the White House used similar language despite the White House’s statement on Friday that it will not release that information. That page has since been removed from the website.

Without that public waiver disclosure, there is no way to know the extent of the Trump administration’s circumvention of its own ethics rules. Even Walter Shaub, the federal government’s top ethics regulator, is in the dark.

“There’s no transparency, and I have no idea how many waivers have been issued,” Shaub told the Times.