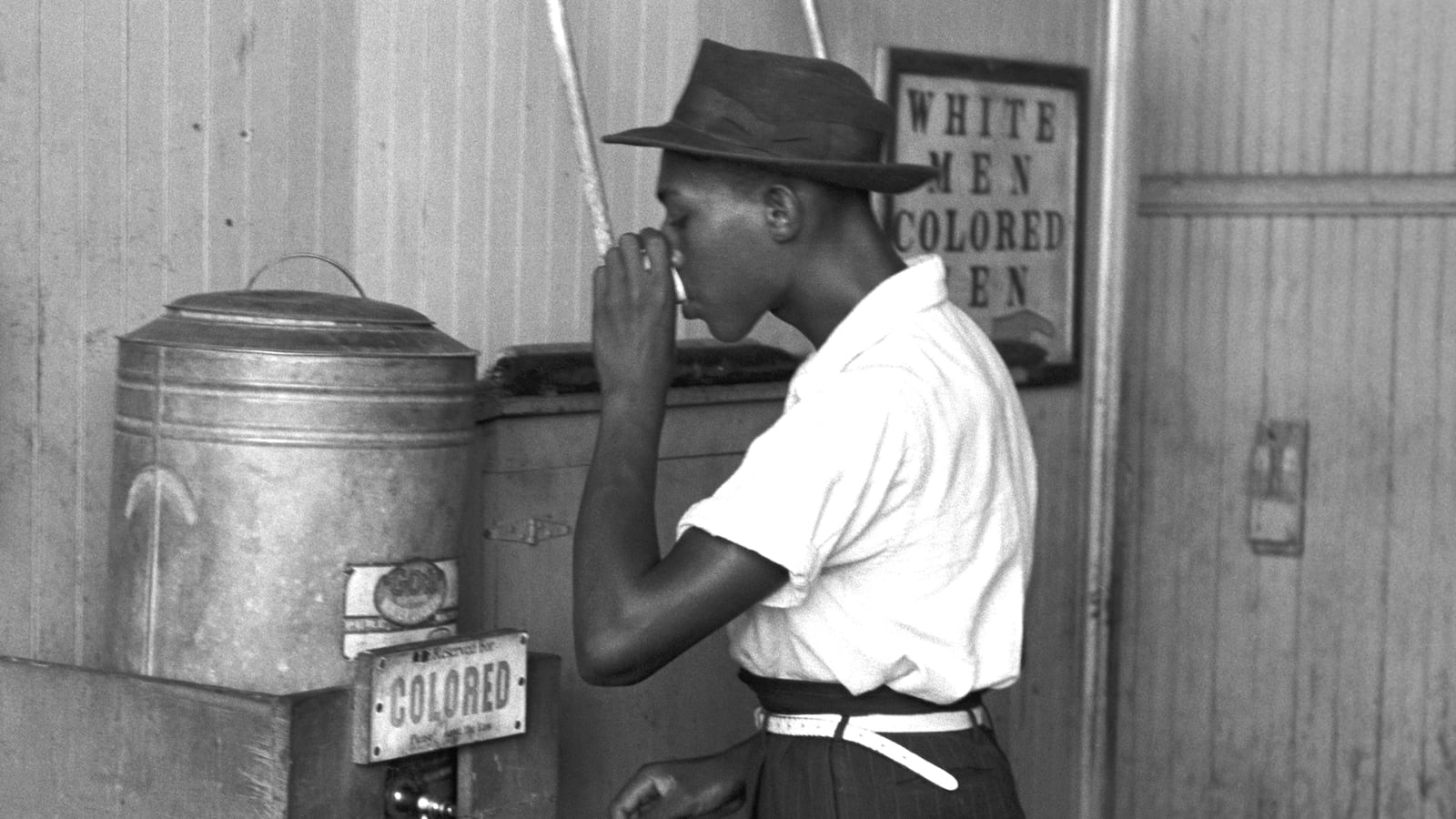

This spring Plessy v. Ferguson, the historic 1896 Supreme Court ruling that racially separate but equal public facilities do not violate the Constitution, marks its 120th anniversary. Today, we view Plessy v. Ferguson as the legal lynchpin of the Jim Crow South, and as we celebrate Black History Month, Plessy epitomizes the kind of Supreme Court decision most of us want to forget.

We prefer instead to remember the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, in which a unanimous Court concluded separate but equal has no place in education and Chief Justice Earl Warren put the nail in the coffin of Plessy, declaring, “Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this opinion is rejected.”

But at a time when the Supreme Court has already weakened the Voting Rights Act and the next appointment to the Court could jeopardize progress on affirmative action, we make a mistake if we ignore all of Plessy.

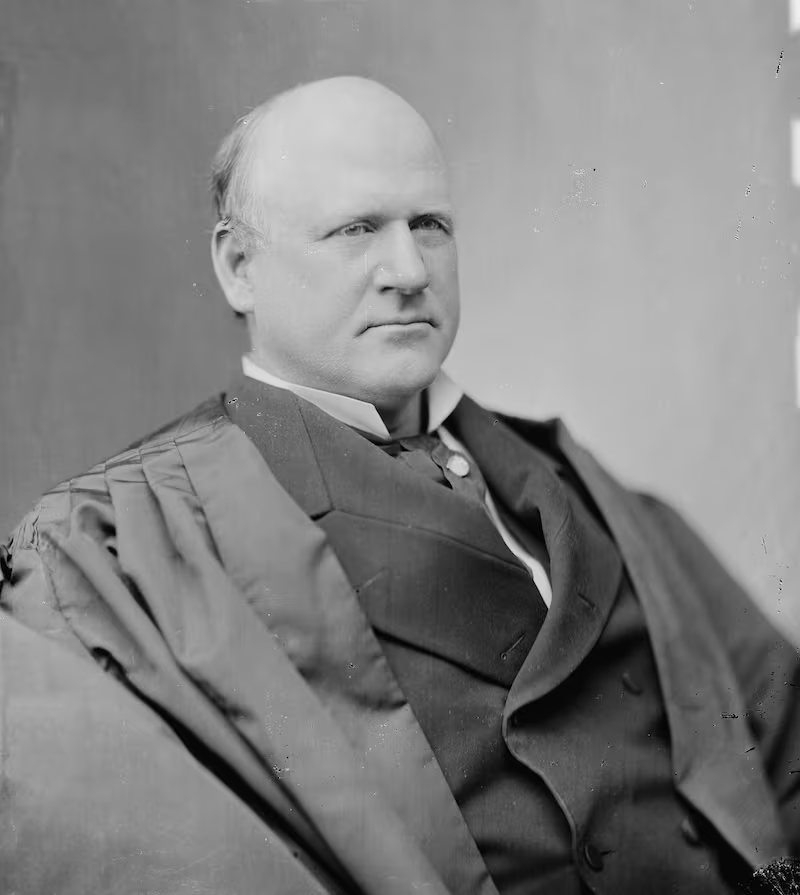

Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lone dissent in the Court’s 7-1 Plessy decision speaks to us today in what it says both about judicial courage and the power of a dissent to guide how future generations think about race in America. It’s no accident that Thurgood Marshall, who led the NAACP lawyers to victory in the Brown case and later became the first black Supreme Court justice, was an admirer of Harlan.

The events that led to Plessy began on June 7, 1892, when Homer Plessy, who was light enough to pass for white, boarded the whites-only car of the East Louisiana Railway train. Plessy then informed the conductor he was black, and he was immediately arrested according to a prearranged plan. Plessy, himself an activist, was challenging a law, the Separate Car Act, passed in 1890 by the Louisiana General Assembly, that required separate but equal accommodations for blacks and whites on trains.

The conservative majority of the Supreme Court had already shown its willingness to do what it could to stop the post-Civil War Congress from expanding civil rights. In the Civil Rights cases of 1883, the Court, with Justice Harlan as the single dissenter, neutralized the Civil Rights Act of 1875, ruling that an individual could bar an African American from an inn or public conveyance without violating the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendment. “It would be running the slavery argument into the ground” to make it apply in such personal cases, the Court held by an 8-1 margin in an opinion written by Justice Joseph P. Bradley.

Plessy represented a more serious challenge to the Court, since what was at issue was not just an individual act. The Court was ready for the new challenge. Justice Henry Billings Brown, speaking for the conservative majority, had no trouble ruling that the Louisiana law separating blacks and whites on railroad trains was constitutional so long as the two races were provided with equal accommodations.

Any notion that this separation stamped African Americans with a “badge of inferiority,” Brown declared, came “solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.” That was, he insisted, a false assumption, just as it was a false assumption to believe “social prejudices may be overcome by legislation and that equal rights cannot be secured to the negro except by an enforced commingling of the two races.” Brown was right in thinking his decision would be widely accepted in the country and cause little stir. When The New York Times reported his decision the next day, it ran the story on its third page in a column titled “News of the Railroads.”

In his dissent Justice Harlan made no effort to disguise the extent of his disagreement with the Court’s majority. Born in 1833 in Kentucky, Harlan had grown up in a slave-holding family, and as a politician, he made a point of acknowledging that his views on race had changed. “I have lived long enough to feel and declare, as I do this night,” Harlan told voters during his unsuccessful 1871 campaign for Kentucky governor, “that the most perfect despotism that ever existed on this earth was the institution of American slavery.”

The Court’s decision in Plessy extended that grim racial legacy, Harlan believed. The decision would, he declared, convey the message that it was possible for the Court to defeat the goals that the recently passed Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution had been designed to achieve.

Harlan pointed out that what the majority of the Court ignored in insisting that the Louisiana statute did not discriminate was the history behind the statute: “Everyone knows that the statute in question had its origin and purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons.”

Such thinking reflected the assumptions whites in America made about their social ranking. “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in America. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power,” Harlan conceded.

“But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens,” Harlan, idealizing the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, declared in the most memorable passage in his dissent.

There was no end to what a state could prescribe if the logic of Plessy were carried to its conclusion, Harlan warned. “Why may it not, upon like grounds, punish whites and blacks together who ride together in street cars or in open vehicles on a public road or street? Why may it not require sheriffs to assign whites to one side of a court-room and blacks to the other?” he asked in a series of mocking, rhetorical questions.

Today, Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson is embedded in our civil rights law to a degree that would have been hard for him to imagine in 1896 when he was such an isolated figure on the Court and made a point of insisting that the “destinies of the two races, in this country, are indissolubly linked.”

But the momentousness of Harlan’s dissent was recognized at the time of his death in 1911 on at least one occasion that did him justice and resonates today. At the African Methodist Episcopalian Church in Washington, D. C. that he went to in 1895 for the funeral of Frederick Douglass, Harlan was honored, as his biographer Linda Przybyszewski has pointed out, with a memorial service of his own. The program for the service had Harlan’s picture on the cover and below it the caption, “A True Friend of the People.”

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.