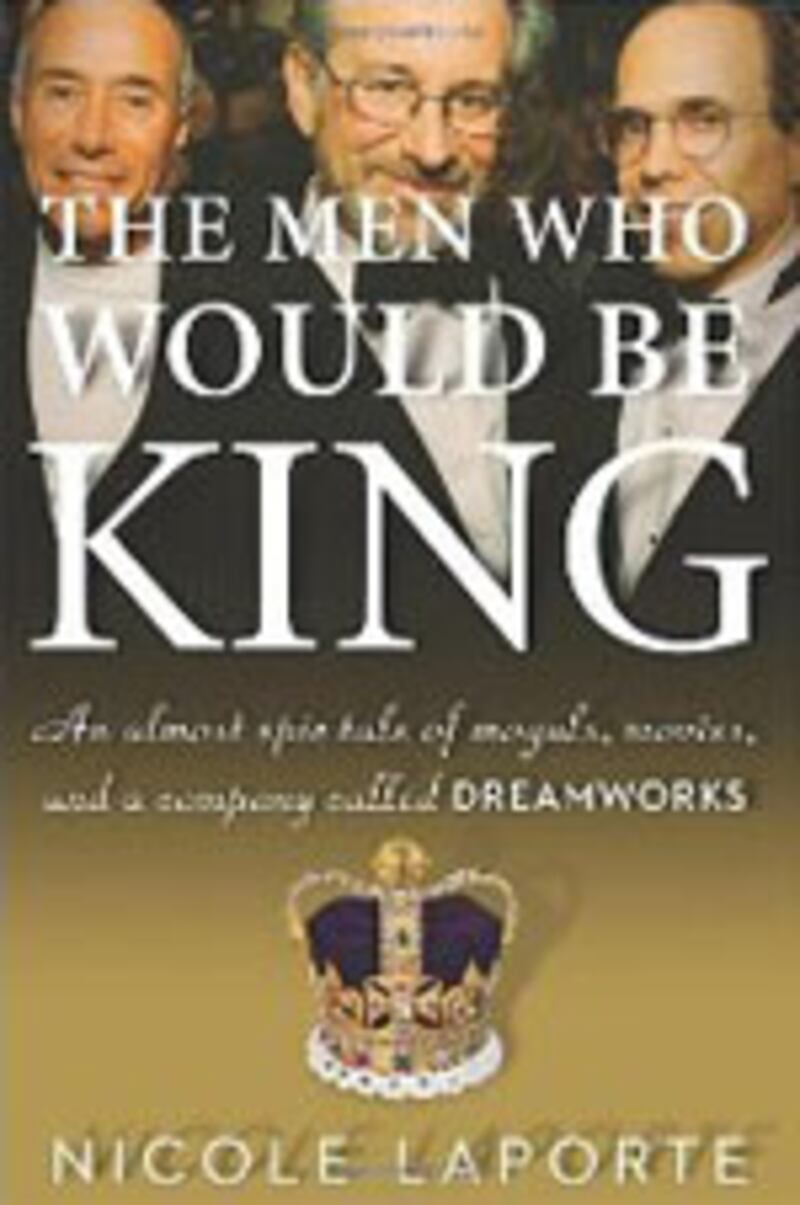

At the center of The Men Who Would Be King is Steven Spielberg, the director so successful that even David Geffen and Jeffrey Katzenberg, his Hollywood-savvy partners at DreamWorks, did not blink when it came to pouring money into the elaborate media empire that Spielberg envisioned when they first formed their company in 1994. As Geffen put it: "When we first started DreamWorks, I said to Jeffrey, 'We ought to call this new company the Spielberg Brothers. Anything Steven thinks is important, we want to invest in.'" Spielberg's life had always been as carefully choreographed as his movies. There were no imperfections, no bad lighting—at least, not before DreamWorks.

Even Spielberg's home life was suitable for framing. His wife, the actress Kate Capshaw, once described her neighborhood, the Pacific Palisades, as "sidewalky," but the Spielberg's main residence is a sprawling estate overlooking the Riviera Country Club where Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn once teed off. Neighbors include Tom Hanks, Tom Cruise, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Here, among kids' toys and baseball bats, original Rockwells and Remingtons, and treasures such as the balsa-wood Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane, Spielberg had achieved the perfect mise en scène he had craved after his breakup with the actress Amy Irving. Capshaw, a former Missouri schoolteacher, helped cure his disillusionment with marriage (Spielberg lists his parents' divorce and his own from Irving as the most difficult times in his life) by putting her acting career aside, starting couples' therapy, signing a pre-nup, and converting to Judaism. "Kate made it clear she'd be a different kind of woman—a supporting, loving and present wife," one source told me. "What Amy was not."

“Walter Parkes is Steven’s idea of what he should have been—East Coast-educated, upper-middle-class family, good-looking guy, right wife the first time, not the second time,” said producer Tony Ludwig.

The director's professional life was equally choreographed—though more stringently, even obsessively, controlled. For despite his menschy, laid-back, good-guy image, Spielberg is an intense power player who cares deeply about financial matters. Says a former agent from CAA, the agency that represents him: "He's probably the toughest person who ever lived, with the added aggravation that he wants everyone to like it. It's that star thing. He has people around who make his wishes come true before he even expresses them. There's a whole phalanx." Not that Spielberg himself liked to negotiate. He hated actually dealing with business matters, preferring to play the role of the likable artiste. The dirty work was left to the agents, lawyers, and managers who genuflected before him and who dreaded the days there was anything resembling bad news to report.

Amblin, his production company that pre-dated DreamWorks, had been created to serve its star resident to an almost surreal degree. Screenwriter Richard Christian Matheson tells the story of a jaunt around the lush campus with Spielberg: "Every once in a while, from a rock or a tree, you'd hear, 'Steven, your 2:30 is here.' Obviously, there were microphones among the rocks that talk, because you'd hear a voice saying, 'Steven do you want something?' He'd say, 'Guys, do you want some Popsicles?' And then he would say to nobody, 'Bring us three root-beer Popsicles!' The whole place was obviously tracking his whereabouts."

For protection, Spielberg had always had surrogate parents, such as the late Lew Wasserman and Sid Sheinberg, the legends of Universal. Amblin, meanwhile, was overseen by the husband-and-wife team of Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall, who tended to Steven's day-to-day affairs and were referred to as the "parents." Kennedy, a scrubbed, athletic type whose style was forceful diplomacy, understood that working for Spielberg wasn't just about execution; it was about cushioning him from the harsher truths. When her husband left Amblin to set up a production company elsewhere, the idea was that Kennedy would follow. The couple wanted lives of their own. But Spielberg was so upset over the prospect of her leaving—considering it a kind of desertion—that in retaliation he forced her to delay her departure. At Amblin, the situation was labeled "the divorce."

At DreamWorks, Spielberg replaced the aging, disempowered Wasserman and Sheinberg with guardians just as tough: Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen. Assuming the Kennedy/Marshall roles were another husband-and-wife team, Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, who ran DreamWorks' live-action studio. Hollywood was shocked when that job did not go to Katzenberg, who had nearly 20 years of studio experience (Katzenberg himself was pained and embarrassed by the news, according to friends), considering that, between them, Parkes, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter and MacDonald, a former junior studio VP, had virtually none. But for Spielberg, it was a no-brainer: He believed in the couple, trusted them above anyone, and valued their sophistication, class, and taste. For a man, who as one person says, "falls in love with people," Spielberg was enamored of his friends, most especially Parkes, a tall, unnervingly good-looking Yalie whose overpowering confidence and verbal agility caused one associate to describe him as "a Shakespearian actor holding forth on the Globe stage."

No one could miss the Freudian implications of the relationship between the nerdy boy-man, who, growing up in unkind suburbia, had wanted "to be a gentile with the same intensity that I wanted to be a filmmaker" and this chiseled golden boy, who had grown up as Wally Fishman in Beverly Hills, but changed his name to Parkes when he landed in New Haven.

"Walter Parkes is Steven's idea of what he should have been—East Coast-educated, upper-middle-class family, good-looking guy, right wife the first time, not the second time," said producer Tony Ludwig.

Unlike most, Parkes wasn't afraid to stand up to Spielberg, and had no trouble telling the director that some of his ideas were harebrained, or, worse, low-brow.

"Walter wasn't afraid to bully Steven," said one insider, "with everything—his looks, his ideas."

But the couple's inexperience running a studio became apparently almost immediately—it would take three long years before any movies were released, a fact that drove Katzenberg, especially, mad (at one point he confronted Parkes at a company retreat: " Where are my movies, Walter?"—and Parkes' propensity to rewrite scripts and bully not just Spielberg, but filmmakers, with his healthy ego, would ultimately make DreamWorks quite the opposite of what it set out to be at its inception: an artist unfriendly place.

Spielberg, however, wasn't concerned, and in fact rewarded Parkes and MacDonald in such a grandiose way that left others at the company dumbfounded. It had happened after Gladiator, a film that Parkes slaved on, was a both commercial and critical success—it would get the Best Picture Oscar. Disappointed that, as studio executives, they were not able to share in the film's success, Parkes and MacDonald decided they wanted to step down and go back to producing. There was only one problem—at the prospect of yet another one of his family members abandoning him, Spielberg said, No way. Willing to do whatever it took to keep them in the fold, he came up with a proposal: What if they were able to run the studio and produce (and be compensated for producing) movies? Despite the far more financially pragmatic Geffen and Katzenberg's reservations, the couple soon signed what others in the company referred to as "the deal of the century" in which Parkes and MacDonald received a whopping 7.5 percent producing fee, which is what mega producers such as Scott Rudin and Jerry Bruckheimer receive. It would prove to be the most controversial, and devastating decision that Spielberg would make, hurting his company, and his relationship with his best friends, in ways he never could have imagined.

Other Spielberg decisions would also negatively affect DreamWorks, from passion projects such as Playa Vista, the "studio of the 21st century" that never came to pass; to divisions such as DreamWorks Interactive (producer of videogames), which Spielberg believed in fervently but ultimately spread the company too thin and had to be shuttered; to sweetheart deals such as the one given to Spielberg's close friend, director Robert Zemeckis, whose production company, Image Movers, was based at DreamWorks for many years, as DreamWorks poured money into the operation in exchange for very few movies.

By 2005, DreamWorks was longer able to go it alone as a result of many of Spielberg's irresponsible decisions, and was sold to Paramount. The marriage would prove disastrous, and brief, leading DreamWorks to relaunch, again, as an independent studio, this time much smaller, much more modest in its ambitions. As for Geffen and Katzenberg, they would be gone. Spielberg, for the first time in his career, would be on his own. Unguarded, unprotected, forced to find his way without the guidance of his guardians. The boy, at long last, would have to finally become a man.

Nicole LaPorte is the senior West Coast correspondent for The Daily Beast. A former film reporter for Variety, she has also written for The New Yorker, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, The New York Times, The New York Observer, and W.