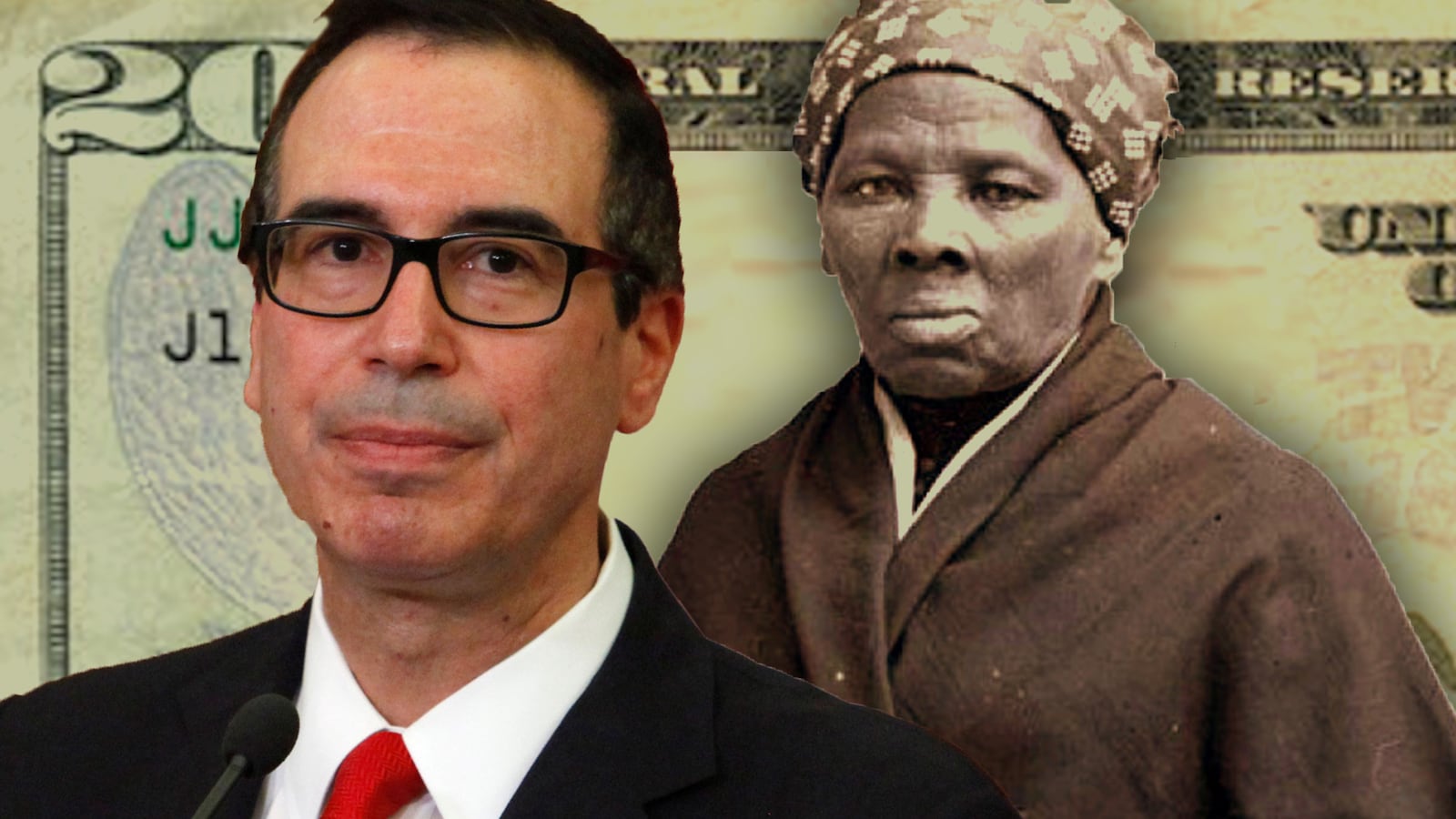

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin says that he will revisit the decision to put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. If his deliberations show any respect for why we have a national currency in the first place, not only should he place Tubman on our greenbacks, but he should come up with reasons to place even more African Americans on our currency.

No one is expecting Mnuchin to reach this conclusion, and most wouldn’t be surprised if he reversed the decision and kept Andrew Jackson on the bill. The Trump administration and its supporters are waging a war on America’s fact-based history, so one would be naïve to expect Mnuchin to break ranks.

As Mnuchin oversees our national currency, and as we debate who should and shouldn’t be on our money, we need to understand that America didn’t truly have a national currency until the Civil War. In the early decades of the republic, states issued their own currencies, but to a significant extent people just bartered because after some “panics” (depressions), no one trusted that these pieces of paper had any actual value.

But then came the war, which the Union had to finance. To do so, the Treasury began issuing Demand Notes in 1861. Demand Notes were printed on both sides, with a green backside. They were the original “greenbacks.” However, as the war grew more expensive Lincoln and the Union needed other ways to finance the war. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 allowed the treasury to print paper money to pay soldiers, buy goods and services, and keep the war going. These bills also had a green backside, so they too were called “greenbacks.”

While greenbacks began flooding the market, American banking remained largely decentralized and states continued to issue their own currency. Exchanging greenbacks for Ohio “bucks” or Connecticut “coins,” became an obvious nuisance for the Union and the National Bank Act of 1863 centralized American banking around a single federal currency.

The Confederacy also created its own centralized currency and issued war bonds to help finance the war.

In other words, America has a national currency due only to the Civil War—that is, only because 11 states broke off to fight for slavery. So you might think that celebrating those who fought to end slavery and win the Civil War should be a prominent theme displayed on our money. Tubman and other abolitionists — both black and white — should be on our money because without their efforts we wouldn’t even have our money, let alone our nation.

Tubman’s contributions to the Underground Railroad are what most Americans know her from, but she also served as a scout, spy and nurse for the Union during the Civil War. Following the war, she settled in Auburn, New York, remained a vocal advocate for the empowerment of black people and black women, and continued to help freed blacks settle and start new lives in the North until her death in 1913. Despite her notoriety and role in shaping this nation, economic hardships remained a persistent struggle, yet Tubman continued to donate her time and money to improve the lives of black people.

There are ample reasons why Tubman should be added to the $20, and ironically the elevation of Andrew Jackson over the last 150 years demonstrates the difficulty of placing her on our currency.

Andrew Jackson died in 1845, yet in 1863 he had a sudden resurgence in popularity when the Union decided to issue a 2-cent stamp featuring Jackson. The stamp was printed with black ink and was affectionately called the “Black Jack.” Upon hearing of the commission of the Black Jack, the Confederacy was outraged that the Union would create a stamp celebrating one of their “heroes,” so they quickly created the “Red Jack,” with red ink, to thumb their nose at the Union. Jackson was a slaveholder of course but was also a believer in the Union, so there were reasons that both sides might claim him.

From this point on the South has always sought to elevate, celebrate and gloss over the horrors of Jackson’s presidency. He has served as the de facto predecessor of the Lost Cause movement that aims to re-imagine Confederate traitors as heroes. Following Trump’s election the Lost Cause has witnessed a resurgence. Charlottesville, which originated as a protest against the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue, represents one of many examples of the increased presence of this movement. Thankfully, the Lost Cause propagandists have been confronted by mayors, historians, and everyday Americans who don’t want our society defined by their oppressive rhetoric. Trump is also a known admirer of Jackson.

Jackson had died over a decade before he could have possibly pledged allegiance to the Confederacy, but the South has always defended him alongside Lee, and Jefferson Davis. They’ve worked to suppress the horrors of the Trail of Tears, and celebrate him as a true populist. Additionally, Jackson despised centralized banking and in 1833 he shut down the Second Bank of the United States. Honestly, Jackson would probably hate to be the face of a centralized currency and have Mnuchin, who worked for nearly two decades at Goldman Sachs, defending him.

As America began putting itself back together following the war and further establishing our national currency and central banking system, Jackson’s face kept on popping up on American currency. Davis and Lee were clearly out of the question, so elevating Jackson made the most sense. And in 1928, Jackson, who had been on the $10 note, was selected to replace Grover Cleveland on the $20 bill. (America has never recovered from the trauma of losing Cleveland on our greenbacks.) In 1929, Alexander Hamilton, the founder of the Treasury, was placed on the $10 bill. This has been the last major shuffle of our currency—almost 90 years ago.

Jackson’s longevity coincides with the South’s determination to rewrite American history, so that it caters to their fragile identity that employs a genteel facade to mask unspeakable horrors. Tubman represents the literal escape from these horrors and the fracturing of the facade. America’s national currency exists today due our commitment to end slavery in the 1860s, yet today we still have discussions about whether someone who worked to free the enslaved deserves to represent America on our currency instead of a Southern slave owner who despised centralized banking.

If Mnuchin actually cared about accurately depicting American values on our currency there would be no need to now “consider” Tubman’s face on the $20 bill. Instead we would discuss how we could elevate even more abolitionists, racial equality advocates, suffragettes and civil rights champions on our money.