We are the most uncool people in Miami, and we can hardly control our bliss. On a warm April morning, thousands of us have packed into the city’s port; one hand on the suitcase, one hand gripping the passport. One tedious line is the only thing keeping us from the “Cruise to the Edge,” four nights and five days in paradise with the living gods of progressive rock.

Once we beat that line, the naysayers—millions of them, tens of millions—will be separated from us by international waters. Miami’s port is as anonymous as a government building gets, but as we shuffle forward, we feel a growing safety in our numbers. Hawaiian shirts unfurl, revealing tattered Yes tour tees and gear from forgotten festivals. The cruise company takes over the PA system, and obscure progressive music pipes in. “What’s this?” asks one cruisemate, hearing a minor-key piano playing under a flanging guitar. “It sounds like Nektar.”

It’s a good guess, one that only a small number of music heads would make. I use my last minutes of terrestrial cell service to identify the song—“Parted Forever,” by Pineapple Thief, a

revivalist band that sounds frozen in 1972. The song is 18 minutes long. Progressive rock is perfect for lengthy, bureaucratic travel tangles.

The “prog rock cruise,” which people have paid thousands of dollars to ride, had been an easy subject for mockery. To enjoy a cruise un-ironically is to give up one’s cool card and set it to the torch. To enjoy “prog rock”—well, what were you doing with that card in the first place? You forged it, didn’t you?

After boarding, and after taking in a few acts, I meet with the people who designed this tour. Larry Morand, manager at Union Entertainment Group, has converted a cigar lounge into a temporary office. It’s been filling up with paper and problems for two weeks, as the Cruise to the Edge is the third of three consecutive music vacations on this 1,092-foot-long ship.

There was “Monsters of Rock,” the metal cruise; everyone understood the marriage of hair metal and poolside mojitos. Then there was the nostalgic Moody Blues cruise, which skewed older and a bit less American. To fill out the Moody Blues bill, UEG had booked some of the band’s contemporaries, like the virtuosic drummer Carl Palmer.

“We were looking at these bands like: Wow, this is another genre, isn’t it?” Morand remembers, after relocating from the cigar lounge to an Italian-style café. “To state the obvious, it was prog, but we learned a lot about the music and the audience on the spot. We called Yes’s manager, and he called back right away: ‘Yes would like to do it.’ And we were off to the races.”

This is a narrative history of progressive rock, told by the people who made it. Many of them told it in real time to the music publications that flowered in the late 1960s, and to the first generation of rock journalists. Most of the stories flow from those sources, though I’ve also relied on memoirs, radio interviews, TV interviews, third-party band histories, and my own conversations with musicians, producers, and fans to reconstruct time and place. This is also an argument for progressive rock as a grand cultural detour that invented much of the music that’s popular now. As the reader will discover—or already knows—“prog’s” reputation has never quite recovered from a series of crises in 1977 and 1978. Punk won over the critics, disco won over the teens, and the major progressive bands deflated like punctured blimps. As of this writing, the blimp’s been patched up and given a second look, but not allowed to fly. The Rock Snob’s Dictionary, originally serialized in Vanity Fair, defined prog as the “single most deplored genre of postwar pop music.” Rolling Stone’s quasi-annual “best albums ever” lists include some Pink Floyd albums but disregard all other prog. In Rip It Up and Start Again, a history of postpunk, there is little mystery about what “it” is or whether its fate was earned.

Rock historians wished it all away. When used in a movie, a Funkadelic or Foghat or Blondie song says “1970s.” A rare prog note in a movie, like Vincent Gallo’s credit of King Crimson and Yes in Buffalo ’66, is meant to invite us into something broken and strange. More often, prog is quoted as a goof—think of Dr. Venture playing prog for his son in The Venture Bros., then panicking when the kid gets stuck “in a Floyd hole.”

Ask a fan how he (yes, usually he) feels about Yes and ELP and Jethro Tull being stonewalled from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame while the Red Hot Chili Peppers—the Red Hot Chili Peppers—make it in.

But prog was fabulously popular for years—and for years, critics liked it. It emerged as a direct response to the throwaway three-minute pop song, the format everyone was trying to emulate after the Beatles perfected it.

Prog was more arty and ambitious than anything else in rock. It was a decadent musical feast in contrast to these pop music popovers. Rolling Stone panned Led Zeppelin’s output and raved about the first Emerson, Lake & Palmer record: “Such a good album it is best heard as a whole,” wrote Lloyd Grossman. Of ELP, the music press declared that they had taken “rock to college.” It was a compliment, not a slur.

Prog’s outsider status was irrelevant on the “Karn Evil Cruise.” (I wish I could claim credit for the term, but it belongs to the music journalist Jeremy D. Larson.) The audience of some three thousand fans skewed boomer; the T-shirts were more often faded by time then faded ironically by Target. Everywhere they turned, there was a prog fan, or a musician.

There was Roger Dean, the artist of so many space-scape album covers, putting together a salad from the buffet—delicately, so it did not stain his vest.

There was John Wetton, whose sobriety was not yet well enough known to stop fans from offering him drinks from the Campari bar.

And there was Tony Levin, the famously mustachioed and head-shaved bassist for King Crimson and Peter Gabriel and countless side projects that this crew had actually bought and heard.

“Is there any chance you’ll play Estonia?” pleads one fan. “It’s not up to us,” Levin says grimly.

Progressive rock did not fade across the world as it faded in Britain or the United States. In some countries—countries, sadly, that did not get music labels to build strategies around them—progressive rock music and its forebears remained popular, if cultish. Forty nations were represented on the cruise, a United Nations for people who loved odd time signatures.

“Anybody can play a 4×4 beat,” said Paul Boswell, a 55-year-old cruiser from Jacksonville who was taping every show he could get into. “If you’ve got a box of oats and a pair of hands, you can play 4×4. This is pure chops, what you’re hearing right now.” For many of the musicians, the cruise was an invitation to be trapped with people who idolized them. The phenomenon wasn’t entirely new. As this music had fallen out of fashion, its obsessives had paid premiums to access it in more intimate ways.

The musicians, who could no longer count on large tours or even notice from the media, indulged.

Sometimes that meant VIP packages, and priceless photos with the band. Sometimes, as Mark Howell discovered, it meant you could pay to spend a vacation at a fantasy band camp with Yes. He had discovered the band in 1973, realized “it was everything I’d been searching for,” and then many years and dollars later, found himself jamming with its rhythm section. “Me and Alan White played ‘Pinball Wizard’ together,” said Howell, stopping by a bar between shows. “Good times. I don’t know how else you get memories in life like these cruises. Last year I had a lot of one-on-one time with Carl Palmer.”

Before they were middle-aged—before they were the sort of people who could decamp for a weeklong cruise—who were the fans of progressive music? Who were the progressive musicians? Hippies. Teenagers. Fans who were sure there was something more out there. People who wanted to drop acid and have their pupils bombarded by lasers. Arty types who wanted to find meaning in music, and who—rather than searching for it in short pop songs based on American blues—found it in the quirky Britishness of prog, equal parts twee and subversive.

The musicians, and the audiences, had grown up with rock. They took it seriously. But they didn’t feel constrained. They were more interested in personalizing or stretching the forms passed down to them. Everybody loved the Beatles, but they loved them best when they got weird. “The Beatles,” said guitarist and producer Robert Fripp, “achieve probably better than anyone the ability to make you tap your foot first time round, dig the words sixth time round, and get into the guitar slowly panning the twentieth time.”

This was supposed to be rebellious music. The Louis XVI of the time was the standard pop song structure—creative kryptonite. In a 1974 feature on Yes for Let It Rock magazine, Dave Laing explained that the “basic impetus was a justified discontent with the limitations of the pre-Pepper pop approach—the glorification of image, the three-minute single, the pressure towards repetition of the already successful formula.”

Rejecting the three-minute single in favor of the suite meant rejecting the “establishment” in every way. “It was felt after Sgt. Pepper anybody could do anything in music,” said Yes/King Crimson drummer Bill Bruford in a 1982 interview. “It seemed the wilder the idea musically, the better.”

Prog songwriters weren’t interested in writing “Love Me Do.” They weren’t even interested in love—at least not with a real person. When a woman appeared in a progressive song, she was a presence, not a sex object. King Crimson’s “Lady of the Dancing Water” is captured in a moment of seduction (“pouring my wine in your eyes caged mine glowing”), but instead of being objectified, she’s transformed into a muse.

Yes’s Jon Anderson, who wrote some of the most mystical lyrics in the genre, told me he was trying to convey “discovery of the self and connection with the divine.”

Lots of people were. In the late ’60s, Peter Sinfield was a bored computer programmer and aspiring songwriter. He wrote lyrics for the original iteration of King Crimson, then got hired

by prog supergroup Emerson, Lake & Palmer. “We just thought we were trying to combine music that hadn’t been combined much before,” he says now. “Elements of jazz, and of classical. People think Emerson, Lake & Palmer were a progressive band, but they were just playing classical music.”

Like a lot of the progressives, Sinfield uses the P word only when pushed. “It’s a word invented by journalists, really,” he says. “We didn’t think of ourselves as progressives—not any of us. Not Yes, not Pink Floyd.”

Maybe, but there was pretty wide acceptance of what “progressive” music was. Promoting A Quick One, which features “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” the Who’s nine-minute, six-movement ballad of infidelity, Keith Moon called the album “the kind of progressive material which should enable us to break into America.” Rock critics and record sellers used the term to denote complex music—complicated by long instrumentals, or symphonic parts, or intricate conceptual structure. These were traits that migrated from the European orchestral tradition into prog.

“Most rock music,” says Greg Lake, “was based upon the blues and soul music, and to some extent country and western, gospel. Whereas a lot of progressive music takes its influence from more European roots.”

Lake was King Crimson’s first singer and bassist before he became ELP’s middle initial. “It appealed to some people a lot, but perhaps for the average person—if there is such a thing— it was too complex, too involved, too much to have to think about, too much to have to wrestle with. It’s much easier to have a three-minute song; you can sing the hook because you can remember it, and it’s done with. Bing, bang.”

Prog songwriters wanted to shake up the assumptions listeners brought to pop music. In his 1997 history Rocking the Classics, the music theorist Edward Macan argues that the progressives built their sound by “uniting masculine and feminine musical characteristics.” The electric guitar and the mellotron tape can dominate different sections of the music; neither sound is wasted as filler. The flute, if you gave it to Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson or Focus’s Thijs van Leer, could be played in a rough way that let the listener hear the exertion and breaths of the flautists. On another song it could be played in the classic style, but high and loud in the mix, as vital as the rhythm section.

The masculine/feminine dynamics led to purposefully unsettling music. In the Court of the Crimson King starts with “21st Century Schizoid Man,” which is easiest to categorize as proto–heavy metal. It begins with Fripp playing a distorted nine-note riff, then playing it again but jumping up an octave for the last three notes, then repeating that, until the riff becomes a sort of elephant squeal. Kanye West sampled the first note for 2010’s “Power.” (On his last tour, Lake opened his shows with the Kanye song playing as lasers sprayed the stage.) But “Schizoid Man” doesn’t stay in the proto-metal mode. Ian McDonald, a multi-instrumentalist who had played with army bands, introduces fast, spitting saxophone lines, turning the next sections of the song into hyperactive jazz.

Humans have spent tens of thousands of years learning to perk up when they hear surprising sounds. You needed to tell a saber-toothed tiger from a gust of wind. So the conflicting attitudes, discordant instrumentation, and jerky rhythms and tempos of prog keep us constantly on edge. Even a prog act’s poppiest song, like Pink Floyd’s “Money,” attempts to undermine the assumptions of radio rock. Roger Waters wrote it in 7/4 time (LOUD-quiet-LOUD)—ONE and TWO and one two three | ONE and TWO and one two three . . . The groove is born out of that tiny moment of suspense. Many progressive epics change time signatures from bar to bar.

Defining or categorizing this music is basically impossible. Progression magazine, a glossy quarterly journal that’s been around for more than 20 years, identified at least 19 sub-genres, including “neo-progressive,” “neo-classical progressive,” and “rock in opposition”—the last one coined by Chris Cutler, a drummer for Henry Cow, to describe music you can’t describe.

Better to think of “progressive rock” as a lab for three kinds of musical modes. The first was all retrospection, trying to replace the standard American-derived influences of pop rock with English and European influences—à la Renaissance, or early Genesis, or early Barclay James Harvest.

The second was futurism, and the use of new sounds and new nonrock influences to replace the standard musical modes. Think the continental European bands: Amon Düül II, or Premiata Forneria Marconi, or Magma, the French act that contrived a new language (Kobaïan) for its lyrics.

The third mode was experimentation. “We thought of ourselves as English rock musicians doing our own thing,” said Egg/ National Health keyboard player Dave Stewart to Paul Stump, a British music journalist. “Progressive, we thought, was Genesis and Yes, and all that stuff, which we hated.”

Instead, Stewart wrote music with “19/8 rhythms, polyrhythms, polytonality. It was hard to learn, hard to play, and probably hard to listen to.” It was music that copied nothing and could be replicated by nobody.

The Cruise to the Edge is not a sarcophagus, though it has its tombs. Yes, it quickly becomes clear, are not interested in mingling. Most of the boat’s cabins occupy a tranche of floors in the middle and back of the vessel. The members of Yes, like other headliners, are situated in cabins at the front. If they so choose, they can avoid mixing with the public.

For the most part, that is what they do. Geoff Downes, the ex–Buggles synthesizer player who handles the keyboard in this iteration of the band, mingles with fans. So does Jon Davison, the lead singer who’s been elevated from the next-generation act Glass Hammer to replace original lead singer Jon Anderson. He sits with fans for an ear-splitting performance by Patrick Moraz, the flamboyant Swiss keyboard player made famous by one album with Yes. He takes most of the questions for “Storytellers,” the occasional interview sessions that are featured parts of the cruise.

Almost every interview is proctored by Jon Kirkman, a Liverpudlian radio personality and author whose qualifications include universal superfandom. He beseeches Italy’s PFM to play more shows in the United Kingdom. He asks Edgar Froese, the Tangerine Dream synthesizer guru, if the band would be up for playing on a boat on the Thames. He encourages everyone to be themselves, to talk about the new album.

“It’s the first time I can really make my statement, something that can be 100 percent reflective of my voice,” says Davison, at the windblown Yes interview.

The interviews do not seem to be the highlights of the week for artists. They clamber off at the port of Cozumel, Mexico, for historical excursions of Mayan ruins. Froese, wrapped in a scarf to protect a recent throat surgery, pokes around the ancient stones and evades the actors playing tribal warriors. Steve Hackett, the former Genesis guitarist whose band reinterprets the songs he worked on, enjoys a “Coco Loco” cocktail in the place where a lost civilization once stored grain.

Every cruiser deals in his own way with the pervasive absurdity. “I’ve never been on a cruise ship,” says Mark Kelly, the keyboard player for Marillion, which along with Yes, is the week’s big draw. “It’s nice—when you’re in the theater, you could be anywhere. Well, apart from the slight side-to-side movement.”

There are cynics on board, but they begin to melt too. Two of the less storied acts onboard are Three Friends and Soft Machine Legacy—continuations of the iconic Gentle Giant and Soft Machine, respectively. Three Friends pack every room solid with renditions of intricate, baroque-inspired music. The Legacy spellbinds the small Black and White Lounge with improvisational jazz fusion.

“Roy Babbington is a big figure on bass,” says Jim Meneses, a drummer and experimental—or “new music”—artist from Philadelphia. “Obviously, the drummer is a big deal too. Program- wise, this is very hip, in this setting, on this goddamn boat with Yes next door and Queensrÿche upstairs.”

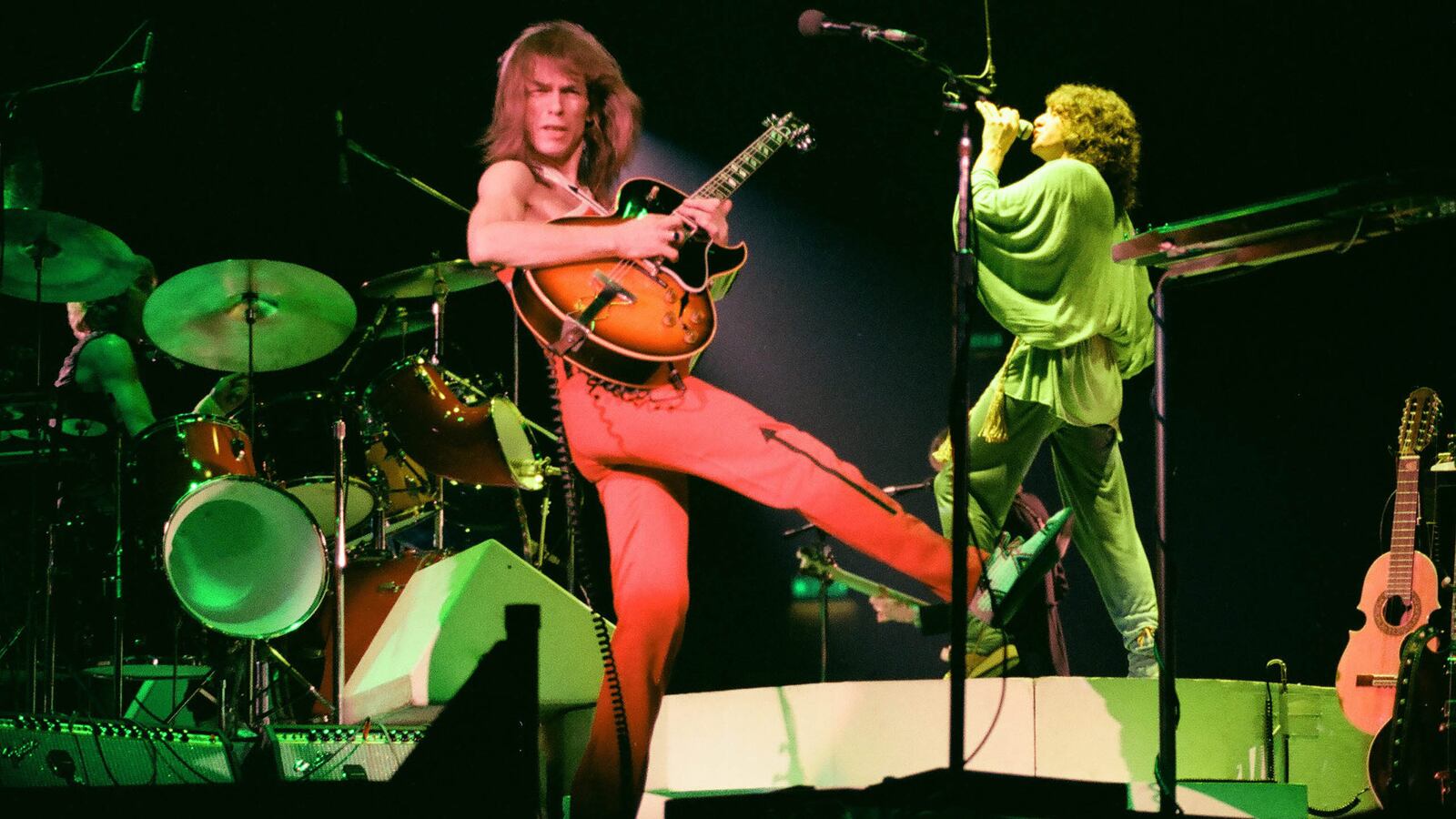

But the big draw remains the least surprising. Yes had preceded the cruise with a series of lucrative shows that featured no new music. They had jumped aboard the trend of playing entire albums in single goes—something they’d done decades before that was trendy, when all 80 minutes of Tales from Topographic Oceans pummeled the audiences of 1973 and 1974. “It adds some excitement for the audience, in terms of knowing what the next track is, of knowing which track follows the other,” bassist Chris Squire says, cheerfully. “It’s a good concept.”

The unquiet secret of Cruise to the Edge is that the concept doesn’t quite come off. By playing three classic albums, note for note, Yes makes the muffed notes more noticeable. A video before each 40-minute block is synced to “The Firebird,” the Stravinsky-inspired song that Yes used to play on stage. The composer’s strings would build, and shudder, and then the band would stroll in, grabbing the melody to toss it elsewhere.

Nice touch. Maybe a bit sepulchral now. On the walk from the theater to one of the all-night lounges, you can hear mega-fans grumble about what went wrong.

They make the best of it. Every night, a too-small bar near the ship’s main theater is co-opted for a “prog jam.” This is not tipsy karaoke; it is a meticulously organized cycle of cover songs, planned months in advance, with the amateur players hauling their instruments onboard. Greg Bennett, a Florida musician with the nom de plume “Jack the Riffer,” even brings his business cards.

The anorak bands are tight, and word spreads. On the second-to-last night of the cruise, they play “The Gates of Delirium,” Yes’s longest and most melodically complex song, inspired by War and Peace and grounded by Squire’s floor-rumbling bass lines. Squire and his family walk in on the performance, unannounced. The crowd grows. A casino just one floor down is nearly empty; the bar at the back of the boat is the only place to be. Squire sits on a wraparound leather couch, listening to people who grew up on his music play through every note as if it were an orchestral score. He dabs away tears. When the performance ends—22 minutes later—he leads the standing ovation.