Not that long ago, if you wanted to see some fine art you had to buy a drink.

In the late 1800s, before museums and galleries were commonplace, the country’s poshest bars drew crowds with their impressive paintings, drawings, engravings, and collections of artifacts.

Renowned bartender Jim Meehan writes in his introduction to a recent reprint of the Hoffman House Bartender’s Guide that it was William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s 1873 oversized and controversial oil painting, “Nymphs and Satyr,” that took bar art to a new level.

The 8½-foot-tall canvas hung in the bar of New York’s legendary Hoffman House Hotel, at the corner of Broadway and 25th Street, from 1888 to 1901 and was purchased by the establishment’s owner, Edward S. Stokes, for $10,010. “A price well worth paying since the painting brought visitors from all over the world to see it,” wrote Meehan.

“Buffalo Bill, the gruff Ulysses S. Grant and countless cattlemen, oil men, horse breeders, merchant princes and bediamonded politicians never tired, though, of feasting their eyes on the figures in the canvas, particularly when the cups brimmed over,” The New York Times reported in January 1943, after the painting had been rediscovered in a West Side warehouse. “There was a legend at the great square bar in the Hoffman House that, seen through a quick succession of Planter’s Punches or persistent rounds of slings, toddies, smashes and sours, the Bouguereau nymphs would stir to life.”

Looking at the piece today, sober, it’s hard to imagine that it created a sensation. But at the time the work was in fact scandalous, as it depicted a number of frolicking nude maidens taunting an equally naked satyr. (Most similar paintings of that era tended to depict the satyr as having the upper hand.)

And then there’s the proportions of the painting.

“It’s really arresting because the nudes are basically life-size,” says Jay Clarke, the Manton curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, which now owns the Bouguereau. “During the Victorian era it was particularly unseemly.”

Today the painting might go unnoticed among the other art in the museum, although Clarke says it sometimes gets a giggle from groups of visiting school kids.

The Hoffman House’s infamous painting made serious art a requirement for any bar with aspirations of class, along with a deep selection of spirits and expertly made cocktails. Not to be outdone, John Jacob Astor IV commissioned Maxfield Parrish a few years later to paint a 30-foot-long portrait of Old King Cole and his court for his Knickerbocker hotel on 42nd Street, a few blocks uptown from Hoffman House.

It supposedly took $5,000 to convince Parrish to undertake the painting. (However, the artist may have gotten the last laugh, since according to lore, the king is based on Astor, and his chamberlains are laughing because his majesty has just passed gas.) While the hotel closed shortly after the work was finished, it found a new home in the St. Regis hotel on 55th Street, where it is still on view in what is now fittingly called the King Cole Bar.

Across the country, for the opening of the stately San Francisco Palace Hotel in 1909, Parrish created another epic painting for the establishment’s wood-paneled bar. This time the artist was paid $6,000 for his wall-size depiction of the Pied Piper, and he based the main character on his own face. (He also featured his wife, mistress, and sons in the crowd.)

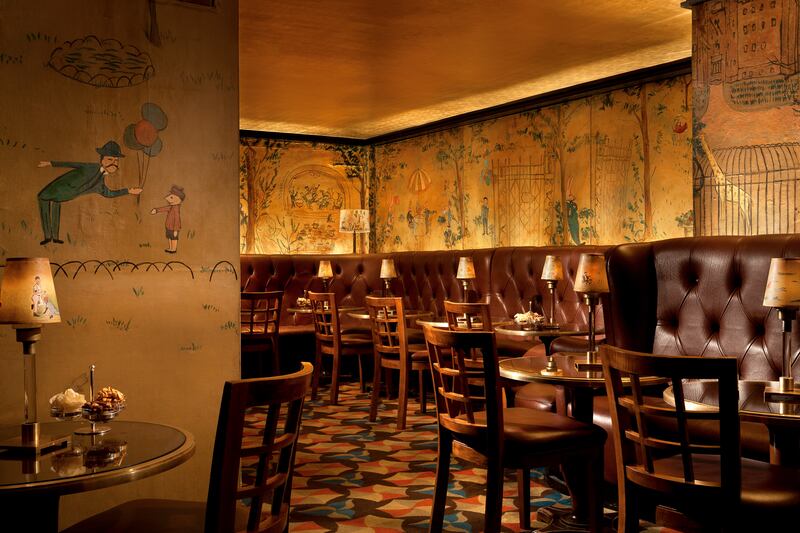

Parrish isn’t the only artist who is famously tied to a barroom. In 1947, Ludwig Bemelmans, who created the colorful and timeless Madeline children’s books, decorated the walls of the bar inside The Carlyle Hotel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side with whimsical scenes of Central Park. The room is now named for him—Bemelmans Bar. In what may go down as one of the best deals of all time, in exchange for Bemelmans’s murals he and his family were given rooms for a year and a half.

A number of contemporary bars carry on the art-loving tradition of their predecessors. Proof on Main in Louisville’s wildly creative 21c Museum Hotel, which actually includes galleries, is perhaps the ultimate example. While the bar stocks hundreds and hundreds of rare bourbons, ryes, and Scotches, what many guests remember about the establishment is its rotating selection of contemporary artwork.

There is, however, one piece that is permanent, a life-size bronze satyr by sculptor L.C. Shank that sits atop one of the corners of the bar top. Be warned: Like the Hoffman House’s Bouguereau, the piece seems to come alive after a few too many whiskies.