The mosque on Kotrova Street in the capital of Dagestan is abuzz with passionate discussions. Here in the northern Caucasus, Muslim revolutionaries are fighting to break away from Russia and create a Salafi “emirate” akin to the caliphate yearned for by Al Qaeda. So people are used to talk about “terrorism.” But they are not used to hearing it linked to words like “Boston” and “marathon.” And they are trying to square what they’re hearing now with their memories of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, 26, the elder of the two brothers at the center of the atrocity in the United States, who was killed last Friday in a Boston suburb.

The men at the mosque on Kotrova Street saw a lot of Tsarnaev last summer and so, it appears, did the local security forces. The FSB, the successor to the KGB, allegedly even had a case file on him, according to one well-placed security source. Tamerlan Tsarnaev was dossier 1713. He was allegedly in the constant company of another Salafist, later killed, whom the FSB believed to have ties to the rebels in Caucasus. The Russian and Dagestani cops were allegedly “watching him closely for five months and three weeks,” according to this source. (The Russians had asked the FBI to take a close look at Tsarnaev in 2011, but the FBI had found nothing on him that they thought worth pursuing.)

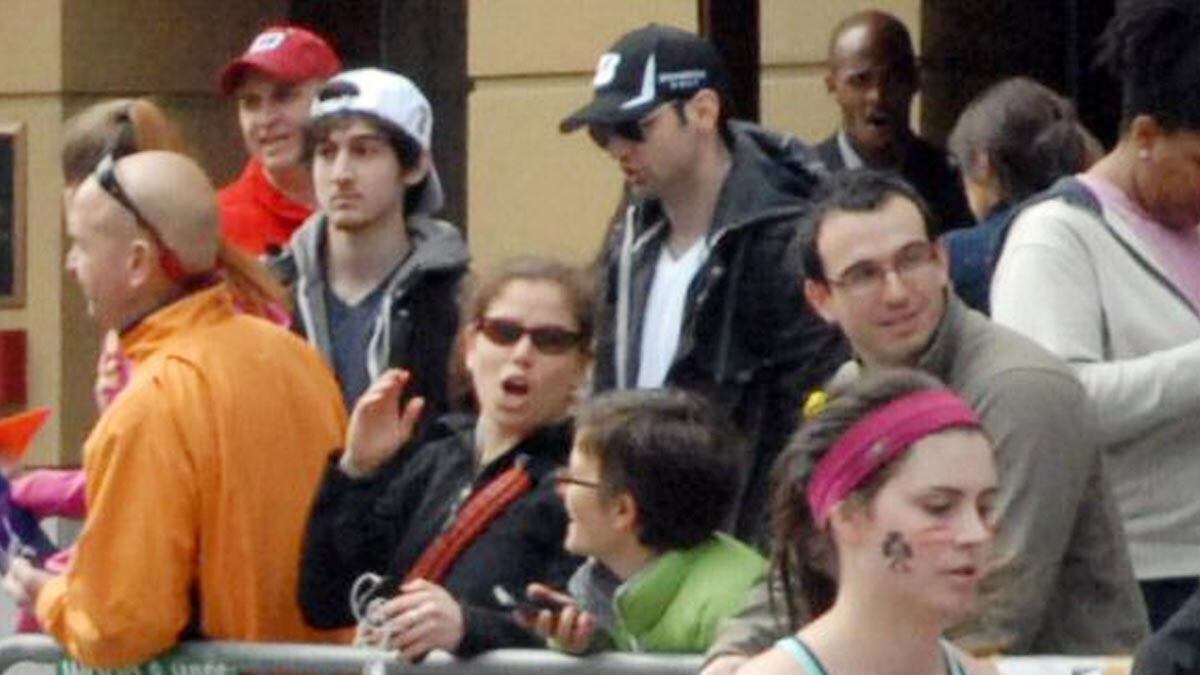

“We remember him well,” says Shamil, a young Salafist at the mosque. “He impressed us, as he was from America.” The Tsarnaev family hailed from Chechnya, in fact, but the boys, Tamerlan and 19-year-old Dzokhar, had never lived there, and they essentially grew up in the United States these past 10 years.

Tamerlan, a boxer who found it increasingly hard to fit in as an American, may well have been searching for his roots in the Caucasus. But in that process, he was discovering and hardening his ties to radical Islamists.

Every man in the group gathered outside the mosque after the afternoon prayer had his own story to tell about persecution at the hands of the Russian state—the same sorts of stories they told to Tamerlan.

“As a rule, special units come to arrest us during every special operation, and our brothers from the community disappear,” says Said, a young man with a thick red beard. “Thirty-five people disappeared in 2007; they were kidnapped by special forces, by the ‘national anti-terrorism committee.’” Another, older man with a dark, lined face pointed at his knees. “They use a drill on you right here to torture you,” he said.

The mosque on Kotrova Street has gained a measure of fame around here. In the 1990s, many young believers from Dagestan went to study in Saudi Arabia. When they returned, many came to this small building with arched windows only a few blocks from the grimy Caspian beach.

Tsarnaev “seemed knowledgeable and serious,” says Said, who is studying Islam at the university. But none of the men in the group outside the mosque could say why somebody like Tamerlan, with a young wife and little child, would want to destroy his own life with an attack like the one on Boston. None had any insights into the connection the brothers thought they might make between the suffering in the Caucasus and the festive crowd they attacked at the finish line of the Boston Marathon on Patriots’ Day.

“I do not believe that the story is so simple,” says Kheda Saratova, a Chechen human rights activist who came from Grozny, the Chechen capital, to investigate. She has hired a lawyer for Tsarnaev’s father, who is now living in Dagestan and has stopped giving interviews. “The parents complain that both the FSB and the FBI framed their children,” says Saratova. “One brother was killed. The other was shot in his neck. He cannot talk—it sounds too convenient.”

But many members of the Tsarnaev family make no excuses for the brothers. “I am so ashamed of the boys,” says Abdurashid Patakhov, one of their mother’s cousins. “How could they get so radicalized in the USA? Why would they kill Americans, if America gave them a free education?

“This is a big trouble for our family,” says Patakhov. “We are afraid of talking because tomorrow we might disappear.”