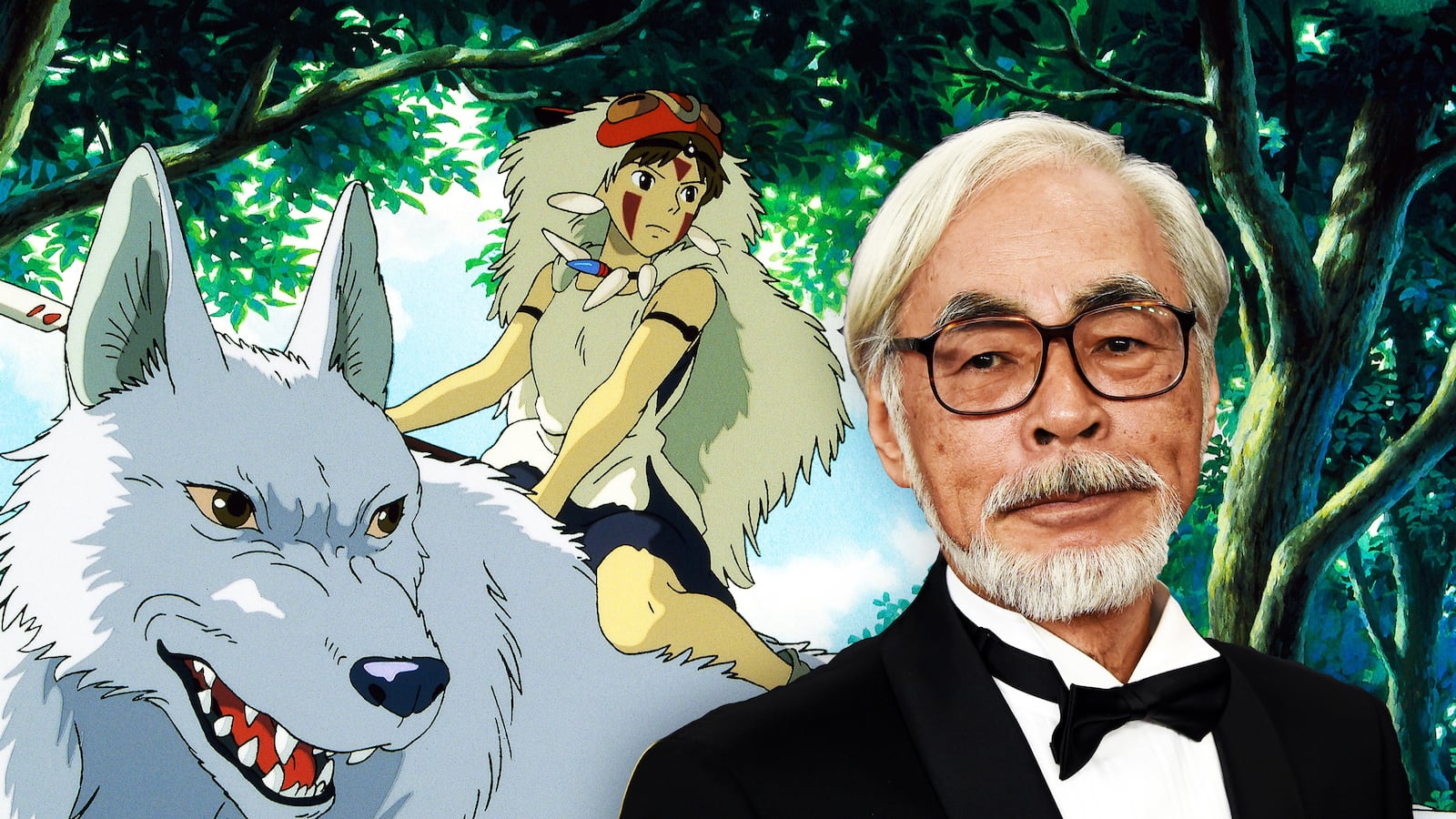

This past Thursday was the 76th birthday of Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary animation artist who’s long been regarded as Japan’s answer to Walt Disney—a reputation only bolstered by the fandom of Pixar chief John Lasseter, who for decades has sung Miyazaki’s praises.

Though revered as a titan in cinephile and animé circles, however, the 76-year-old writer/director’s renown amongst mainstream American moviegoers is still scant, in part because much of his early-career output—made with his production company Studio Ghibli—never received proper stateside releases, from the The Force Awakens-inspiring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) to the peerlessly charming fables My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989). That changed, however, in 1999, with the Miramax-distributed Princess Mononoke, a landmark in modern animation that fully opened the world’s eyes to Miyazaki’s greatness—and, on the eve of its 20th anniversary re-release, remains as timely, and timeless, as ever.

Beginning Monday, January 9th, Americans will be able to (re-)experience Princess Mononoke (in select markets) as it was meant to be seen: on the big screen, where its larger-than-life power and beauty can be properly appreciated. It is, in short, a classic of the form, a sprawling adventure that melds eco-consciousness and spirituality with violence, romance, humor and complex characterizations and emotion. Miyazaki’s film was something of a continuation of Nausicaä’s themes and tones, albeit bolstered by animation that combined hand-drawn work with early-CGI effects to produce images that are breathtaking in their fluidity and power. Miyazaki’s big-eyed facial designs are simple and yet powerfully expressive, which is also true of his figures’ swift, precise, exhilarating movements. Rare is the scene that doesn’t boast some stunning sight or moment at which to marvel, be it an arrow cutting through the air to decapitate a samurai, or a towering translucent Forest Spirit walking slowly, surreally through his woodland home.

Though it’s the first of his films to feature graphic bloodshed, Princess Mononoke—which for its Fathom Events re-release will be presented in its (surprisingly stellar) dubbed-in-English version—is as remarkable for its contemplative qualities as its combat mayhem.

Set in an ancient era, Mononoke’s convoluted story begins with a young prince, Ashitaka (Billy Crudup), saving his rural village from a rampaging boar god who, after eating a ball of iron, was transformed into a red tentacle-covered demon. His right arm infected with the demon’s fatal curse (which gives the limb extraordinary power), Ashitaka ventures West to investigate the true source of this trouble. There, he comes upon Irontown, run by Lady Eboshi (Minnie Driver), a ruthless industrialist whose desire to mine the region of its subterranean iron involves cutting down its acres of trees—a plan that’s angered the ancient spirits of the forest, including Boar God Okkoto (Keith David) and Wolf God Moro (Gillian Anderson), who cares for her adopted human daughter San (Claire Danes), the woodland-warrior princess of Mononoke’s title.

Thus begins a rollicking, rambling saga in which Ashitaka winds up in the middle of Eboshi’s clash with the Gods (and San, who inevitably finds herself caught between two worlds). That scenario is further complicated by Eboshi’s war with a rival samurai clan as well as her entanglement with mercenary monk Jiko-bō (Billy Bob Thornton), who provides her with men and, in return, demands that she procure the head of the Forest Spirit—a creature that appears as a smiling multi-antlered elk by day, and a shining-amphibian colossus by night—which Japan’s emperor believes will grant immortality. If Princess Mononoke is intricately plotted, however, it’s never muddled, instead layering its conflicts upon each other with a meticulousness that’s mirrored by its visuals. In both the characters’ physicality and the plot’s progression, there’s a sense of constant, assured purpose; one can feel Miyazaki orchestrating the proceedings with the utmost confidence.

The same goes for his film’s impossible-to-miss message, which concerns mankind’s relationship to nature—particularly, the perilous consequences of raping the land of its natural resources in service of modern progress. Princess Mononoke’s plea to protect the environment felt ahead of its time in 1999, and it remains striking in its forcefulness. Nonetheless, what truly bolsters Miyazaki’s tale is its refusal to paint this dynamic in simple black-and-white terms. Eboshi’s deforestation quest may make her the nominal “villain,” but like San, she’s cast as a strong, fiercely independent and capable feminist woman. And moreover, her actions are undertaken in order to provide a better future for her people—which include rescued prostitutes and shunned lepers, both of whom she’s mercifully taken under her wing. Meanwhile, the endangered forest gods are far from a wholly cheery bunch: Moro and Okkoto routinely express their desire to not only defeat their human oppressors, but to crunch their skulls between their mighty teeth. Cheery anthropomorphic Disney critters they are not.

Princess Mononoke soon comes to play like a lament, largely because it recognizes that no easy solutions exist for its central conflict. Such maturity extends to its blending of kid-oriented fantasy and more adult-skewing romance (between Ashitaka and San), sexuality (i.e. the aforementioned prostitutes and their playful lusting after Ashitaka), horror (a creepy tribe of apes), and brutality, the last of which comes in curt, concussive bursts. Even more than in his other endeavors—including later masterpieces Spirited Away (2001) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)—Miyazaki here strikes an ideal balance between the worlds of children and grown-ups, a middle ground where amazing beasts and adorable bobble-headed tree spirits (their shaking noggins producing a weird clicking sound) co-exist alongside men and women torn between their thorny responsibilities to Mother Earth and fellow humans.

Concluding on a note of rebirth and tentative hopefulness, Princess Mononoke accepts that two seemingly opposing things can be true at once, all while promoting the notion that the only constructive way forward is through understanding, communication and collaboration. Whether with regards to the environment, politics or the oft-difficult process of dealing with those unlike ourselves, it’s a lesson that’s as vital now as it was upon the film’s release twenty years ago—and one that ultimately helps make Miyazaki’s period-piece adventure a crowning achievement of both breathtaking style and slyly progressive storytelling.