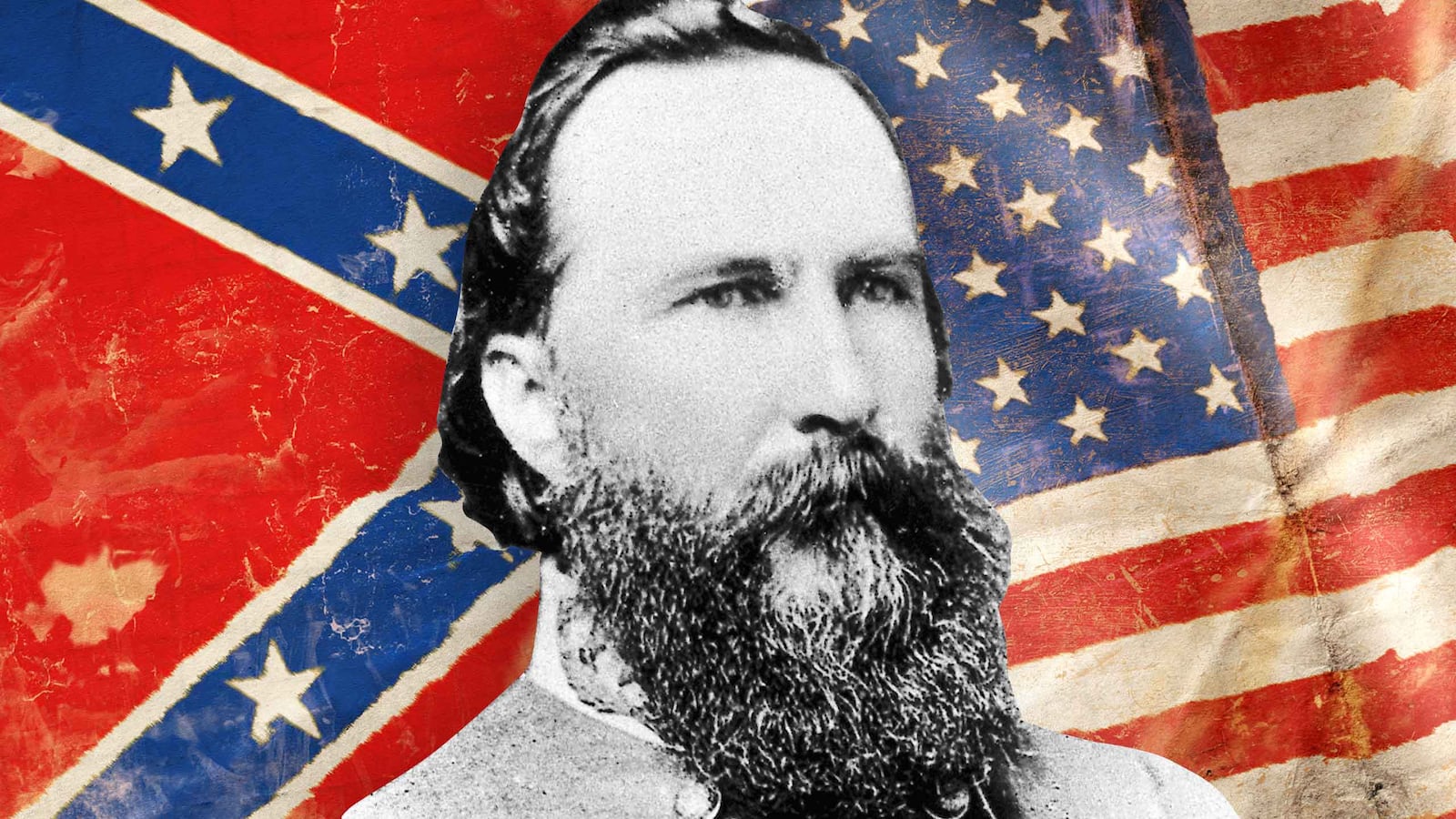

General James Longstreet, was one of the “three persons of the South” whom President Andrew Johnson believed should “never receive amnesty.”

President Johnson was half-right. Longstreet had “given the Union cause too much trouble.” Longstreet never apologized for betraying his country. He never regretted crushing Union troops at bloody battles, including Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. He never renounced his region’s reprehensible pro-slavery war aims. He would write: “That the South had just cause for war in protecting and defending lawful property is proved by the sequel.”

Yet he was no General Lee or Jeff Davis. While other Southerners romanticized “the Lost Cause,” he had the guts to tell Confederate comrades their cause was lost.

Student screw-ups take heart. When James Longstreet was at West Point, he and his schoolmate Ulysses S. Grant seemed doomed to fail in life. Born in 1821 in South Carolina, raised in Georgia and Alabama, Longstreet graduated 54th in a class of 56. Longstreet solidified his lifelong friendship with Grant by introducing a distant cousin, Julia Dent, who eventually became Mrs. Grant.

This dunce in classrooms was brilliant on battlefields. Like George Washington, Longstreet exploited his good looks and 6-foot-2 height. He fought bravely in the Mexican-American War, bearing the regimental colors in the Battle of Chapultepec in 1847. When he was shot clean through the thigh, his schoolmate George Pickett charged up the hill, having picked up the flag.

America’s triumph triggered intense debates about expanding slavery into the once-Mexican territories. By 1860, serving with northerners and southerners, Longstreet dreaded getting the mail. When news of the Civil War arrived, he asked a Northerner “what course he would pursue if his State should pass ordinances of secession and call him to its defence.” The friend “confessed that he would obey the call.”

Longstreet quickly became to the Confederate General Robert E. Lee “the staff in my right hand.” Courageous, cool under fire, and cautious, Longstreet craftily defended his positions so as to “force the enemy” to attack—on his terms. That approach prompted him to dispute Lee, with all “the freedom justified by our close personal and official relations,” when Lee contemplated invading the North in July, 1863, through a little town in Pennsylvania called Gettysburg.

Longstreet feared waves of attacks risked too many lives. In July, 1863, Longstreet also urged Lee to dispatch at least two divisions to repel his old friend U.S. Grant in Tennessee.

Lee overruled Longstreet. On the second day of battle, Longstreet’s ambivalence showed. His chief of staff, Major G. Moxley Sorrel later admitted: “There was apparent apathy in his movements. They lacked the fire and point of his usual bearing on the battlefield.” There was no breakthrough—but no massacre.

The third day, Friday, July 3, Lee demanded a full assault. Longstreet dutifully authorized what became the bloody, futile Pickett’s Charge. “Never was I so depressed,” Longstreet later wrote, as nearly half his force died.

After the Gettysburg defeat, Longstreet fought valiantly on the South’s home turf—although his power struggles with colleagues and subordinates intensified. Still, the historian John Cook considers Longstreet “the outstanding corps commander of the Confederacy.”

In May 1864, during the Battle of the Wilderness, an errant Confederate bullet hit his neck and shoulder, paralyzing his right arm. Nevertheless, Longstreet remained Lee’s “old war horse.” Longstreet reassured Lee that Grant would treat them honorably when they surrendered. Recalling Grant’s elegance then—and a few weeks later when meeting Longstreet with other defeated Confederate officers, Longstreet would think: “Great God! … how my heart swells out to such magnanimous touch of humanity. Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?”

Unlike many comrades, Longstreet accepted defeat. He moved with his family to New Orleans, becoming a cotton broker. In 1867, the New Orleans Times asked former Confederate generals to react to the tough Military Reconstruction Act. Longstreet sounded resigned yet magnanimous—infuriating Southerners unwilling to be either. “The decision was in favor of the North, so that her construction becomes the law, and should be so accepted,” Longstreet acknowledged. He dreamed: “If every one will meet the crisis with proper appreciation of our condition and obligations, the sun will rise to-morrow on a happy people.”

Longstreet warned Southerners not to conclude that “we cannot do no wrong and that Northerners cannot do right.” He said: “I hope to live long enough to see my surviving comrades march side by side with the Union veterans along Pennsylvania Avenue, and then I will die happy.”

Such statements made Southerners unhappy. So too, did his endorsement of Grant and the Republicans in the 1868 presidential campaign. With his new federal job and his friendship with the local regime of Black Freedman and Northern Carpetbaggers—outsiders—Southerners called him a “scalawag,” an epithet they broadened from inferior cows to worthless humans to traitors.

Unresolved Southerners limited African-American freedoms, while rewriting history. When General Lee died in 1870, former associates built Lee up by bashing the perfect foil, Longstreet. False claims that Gettysburg was the turning point of the war, and that Longstreet refused to attack when he had the chance on the second day, made Longstreet the Southerner Southerners loved to hate.

Always grandiose, Southerners defined themselves as the Jesus Christs of America, persecuted by brutal Yankees. This made Longstreet the “Judas of the Lost Cause.” His honest disagreement—and concern for his men, became “culpable disobedience” and “treachery.” History was hijacked; pimped out to serve the Southern agenda of aggrandizing the Confederacy, demonizing the North, and demeaning blacks. Longstreet and his family were shunned in New Orleans. His business opportunities dried up—making federal patronage essential.

“Bad as was being shot by some of our own troops in the battle of the Wilderness—that was an honest mistake, one of the accidents of war,” Longstreet sighed, “being shot at, since the war, by many officers, was worse.”

Unbowed, Longstreet became ever more unpopular. In 1874, the White Leaguers in New Orleans sought to impose a Democratic mayor. Longstreet led black troops against these violent sore losers. Now, he was a “race traitor.” too. In a bloody battle the racists won Longstreet was wounded by real blowback—a spent bullet, a casing fired from his gun or from a nearby comrade’s weapon. President Grant then mobilized enough federal troops to restore order—and avert a second Civil War. Still, in 1891 the South’s mythomaniacs placed a monument hailing this “Battle of Liberty Place,” perpetuating the white supremacist spin. The monument stood in New Orleans until April 24, 2017.

Longstreet fled New Orleans. Returning to his native Georgia, he served in other government positions, wrote his memoirs From Manassas to Appomattox, and continued fighting to clear his name—and educate his region—until he died in 1904.

Longstreet remained an optimist, saying the war instilled “a broader and deeper patriotism in all Americans.” Hoping “to stimulate and evolve this noble sentiment,” he insisted that “what we need is the resumption of fraternity, the hearty restoration and cordial cultivation of neighborly, brotherly relations, faith in Jehovah, and respect for each other.”

Having long insisted “You can’t lead from behind,” Longstreet proved to be as brave in peace as he was in war. He refused to rewrite history. Today, he would resist those who try freeze framing America in any moment. To leftist despair-mongers he would note the progress, the “resumption of fraternity,” in so many ways. To rightist hate-mongers, he would show how all-American is “the cordial cultivation of neighborly, brotherly relations.”

The reasons why Southerners hated General James Longstreet is why we should honor him. “It is my opinion,” he told one tormentor, “that your abuse, so far from impairing my interests or my reputation, will be more likely to enhance them in the estimation of honourable men.” We honorable men and women should vindicate Longstreet.

In honoring his memory and telling his story, we also honor the United States, a country that has never been perfect itself but has never stopped perfecting itself. The Founders’ idealism, the pioneers’ restlessness, even the Robber Barons’ ruthlessness and the unreformed Confederates’ brazenness are in our DNA. It makes us a never-fully-settled people but also a constantly-improving-nation, blessed by that extraordinary mechanism for self-improvement, liberal democracy, and enough heroes like James Longstreet to defeat not just the haters but the skeptics and cynics.

For Further Reading

G. Moxley Sorrel, At the Right Hand of Longstreet: Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer, 1999.

James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America, 2013.

R. L. DiNardo and Albert A. Nofi, James Longstreet: The Man, the Soldier, the Controversy, 1998.

William Garrett Piston, Lee’s Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and his Place in Southern History, 1987.