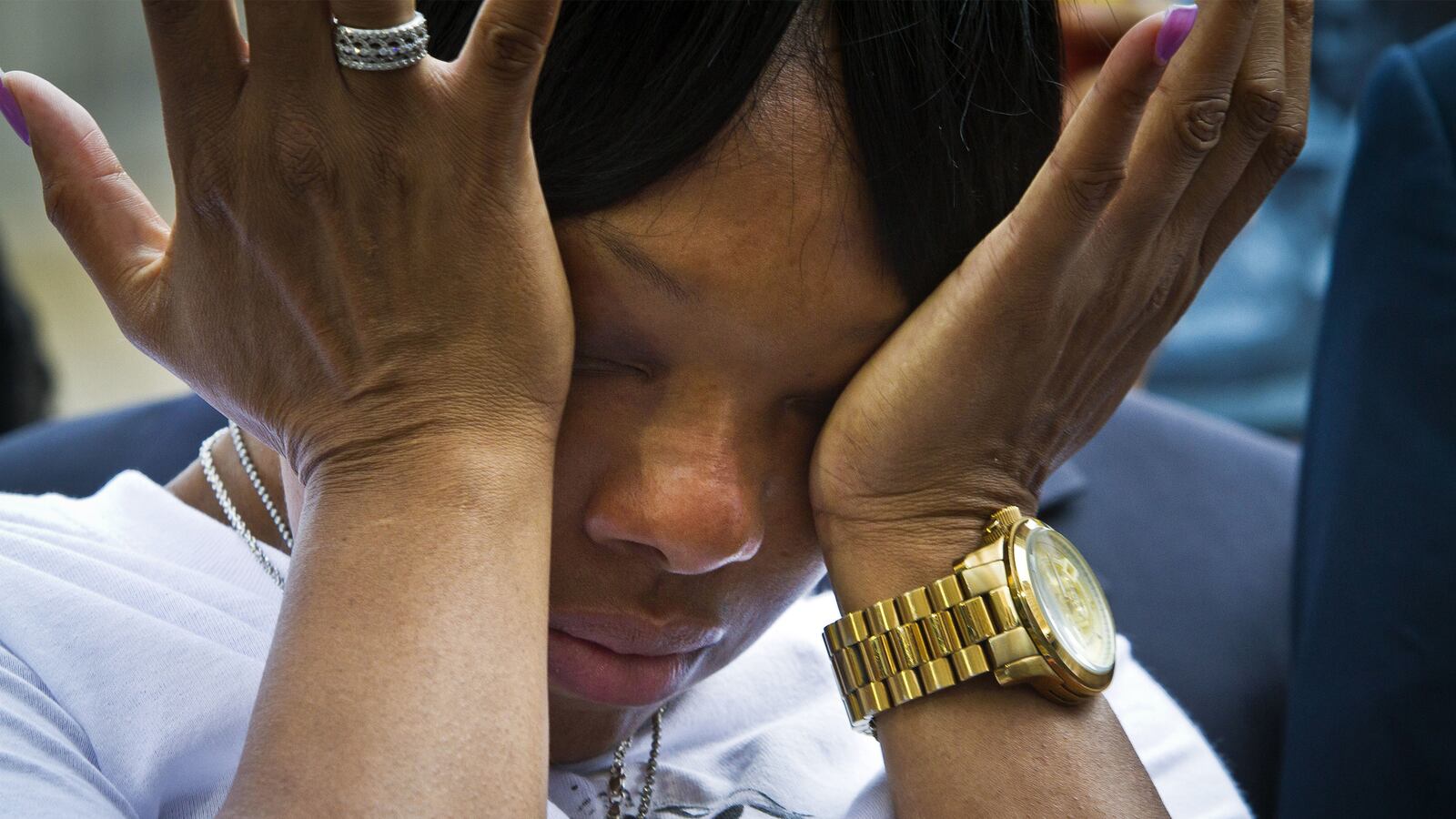

Constance Malcolm came to the Times Square Hilton, to the National Action Network’s annual conference on March 13, to see the mayor. For two months, she and her supporters in the police reform advocacy group the New York Justice Committee had been calling and writing to Mayor Bill De Blasio’s office, asking him to meet with the mother of Ramarley Graham, who at 18 years of age was gunned down by a police officer inside the family’s apartment on Feb. 2, 2012, and to see to it that all of the officers involved are fired from the NYPD.

Four years later, Malcolm knows the names of only two of the up to one dozen officers she and her family say crammed inside the small apartment she rents in a three-family house where the landlady lives upstairs and the landlady’s daughter on the first floor. Officer Richard Haste, the man who shot Ramarley Graham dead, was cleared by a grand jury in 2013, after initially being charged with manslaughter; a trial ended in dismissal by Bronx County Supreme Court Justice Steven Barrett on a technicality. Sergeant Scott Morris has been named in media reports as being the most senior officer on the scene. The mayor’s office has indicated that there is an administrative, disciplinary investigation under way, but to date, it has provided no further details to the family.Malcolm was seated at a round table just a dozen feet from where de Blasio had just completed a press conference at the Hilton, taking questions about a mounting fundraising scandal at City Hall, and about an off-color skit he’d appeared in with Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton (whose Senate campaign de Blasio ran in 2000), in which the punch line, “I was on CPT” was rewritten from “colored people time” to “cautious politician time.”

After the presser, the surprisingly cautious mayor, who ran as a bold liberal, surrounded by his own interracial family, including a teenage son with a sky-high Afro—who Malcolm frequently points out could easily be targeted by police who might not recognize him as the mayor’s son—disappeared into a back room. He never made contact with the parents who’ve lost their children to police violence: Sean Bell’s mother and father, William and Valerie Bell; Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, and Kadiatou Diallo, the regal mother of Amadou Diallo, killed by the famous “41 shots” way back in 1999. Kadiatou has become a kind of grand dame among the mothers dispossessed of their sons at the hands of police officers.

Malcolm says she thought about barging into that press conference and demanding that the mayor talk to her. But she didn’t want to disrespect Rev. Al Sharpton, the National Action Network leader who has supported the families through their pain, their rage, and their cries for justice. (Note: Sharpton is also my MSNBC colleague.)

“He knows what happened to my son,” Malcolm said of De Blasio as we sat in the Hilton lobby at the end of the day. “He knows the whole case because when he was running for mayor, we sat next to each other a couple of times at NAN. He knows. And all I want to do is talk to him. I want to know why these officers are still on the force; why they’re not fired.”

She did have a brief meeting with Hillary Clinton, who was at NAN to speak that day and met with the moms, one of whom, Carr, has publicly supporter her.

“I told her we need accountability,” Malcolm said, “because right now we don’t have that, and our kids are dropping like flies. … These officers, all they have to say is, ‘I thought,’ and that’s their ‘get out of jail free card,’ and it’s wrong.”

Malcolm sees the whole game as rigged. She and the other moms cling to one another and to their faith, but waste none of the latter on the criminal justice system. “[Even] if they do try to indict a police officer,” Malcolm says, “most of the time the D.A. is not for the victim. They don’t advocate for the victim.” She says she has said as much to the Bronx District Attorney, and to the people at the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan, who in March informed Constance and the public that they would not seek federal civil rights charges against Haste or the other officers involved in Ramarley’s death.

Retracing Ramarley Graham’s last moments means traveling to the working-class Wakefield section of the Bronx, to a quiet block lined with modest, two- and three-story multifamily homes, most girded in white wrought iron fencing. Constance and her family still live in the house where her son died; and from the front porch, she can see the corner of 228th and White Plains Road, where he and two friends walked from the store and he parted from them and headed home.

Constance, her younger son, Chinnor, who was just 6 and in the house when his brother died, and her mother, Patricia Hartley, a tiny, bone-thin 62-year-old Jamaican woman she affectionately calls “Patsy,” had lived in the second-floor apartment for just three months when police burst in and unraveled their lives.

With police unresponsive to requests for comment about the incident, I record the women’s account of happened that day.

Patsy was home, having just picked up Chinnor from school when Ramarley arrived at about 3 p.m. He came up the narrow foyer staircase leading to the second floor. He entered the apartment, with its two tiny hallways, one to the left, leading to his mother’s room and Chinnor’s—whose door is papered with his super-hero drawings (now 10 going on 40, he’s a smart, guarded boy who says he wants to be a fireman, but he’d also like to be an artist, maybe on the side) and to the hallway leading to the kitchen and a small bathroom on the right. The living room, where Chinnor hid from the noise and bullets and the yelling, cursing police officers, is straight ahead. The hallway is little more than a shoulder’s width wide. As Constance points out, two people couldn’t fit into it side by side.

Constance now knows, based on video from the cameras mounted on houses, at the store, and along the block, including at the home where Constance and her family live, that Ramarley had been spotted by two undercover police officers from the NYPD’s Street Narcotics Enforcement Unit as he left the corner store. They radioed that they’d seen him “adjust his pants,” which Constance said the gangly teenager like to wear loose. Police initially claimed Ramarley ran from them, but the surveillance footage shows him walking calmly down the street and into the front door. NYPD superintendent Ray Kelly also had to retract a public claim that Ramarley had wrestled with police before he was shot.

Ms. Hartley says she came out of the kitchen as she heard her grandson enter, informing Ramarley that she’d already picked up his little brother, and waiting for him to hand her the front door keys, when the door flew in. She stumbled backwards, standing in front of her grandson, who towered over her (she’s barely 5 feet tall and cannot weigh more than 90 pounds. Even Constance, at around 5 feet, dwarfs her.)

Patricia Hartley moved her family from Jamaica to New York City in 1985, to find a more peaceful place to raise her children. She still bears the scars of a gunshot wound just below her left collarbone. When Haste burst in and started firing, she says she clutched her chest.

“I thought he shot me,” she says in her thick island drawl. “But me never feel no blood, so I turn and see Ramarley’s feet on the floor.”

Ramarley had been shot through the heart, and he fell with his feet protruding from the bathroom; the rest of his body lay inside. Police would later claim he’d run into the bathroom when police entered and tried to flush a bag of marijuana. Constance was told a bag was found, but with no fingerprints on it. Patricia says that day, all the cops were demanding was, “Where is the gun?”

She says she bent to kneel over her grandson, but was ordered by Haste to “back the fuck up” or he would shoot her too. Her size belying a fierceness that’s peculiarly Jamaican, Patricia says she demanded to know why he’d shot her grandson, when he’d done nothing, and called to Chinnor to bring her the phone. By that time, she says, more police had poured into the room, including a woman officer who was ordered by Haste to seize the phone from her and not to let her call anyone. The next few hours were a whirlwind of what the women claim was serial callousness and abuse: Patricia ordered first to sit on her living room couch, not far from her grandson’s lifeless body, then carted downstairs with her remaining grandson while Haste and the other officers were alone in the apartment; then being carted off to the 47th Precinct, where she was interrogated at length; shown a picture of another young man and told that was the person police shot, and called a liar when she denied both that the man in the picture was Ramarley and that he ever had a gun (and even that he’d thrown a gun out a window.)

Constance says when she arrived at the precinct she too was manhandled; thrown against a wall by an officer when she demanded to see her mother. She says the officer who did it was punished only with a notation in his file.

We leave Constance’s house to drive to Gracie Mansion, where she and her supporters, including Mrs. Bell, held a vigil in the frigid spring weather, hoping to convince de Blasio to come outside and talk to her. The police officers on scene are gruff and the tensions mount as they brusquely order the group of about 30 people to set up across the street from the public park surrounding the mayor’s mansion, to a “pen” set up by police public affairs across the street. “We’re not pigs,” Constance tersely tells the officer, as he argues with a Justice Committee member, who stands her ground, and calls the group’s lawyers. Ultimately, the group is allowed to stay, and they watch de Blasio’s black-tinted SUV roll past them into the residence.

Chinnor eyes the cops warily. His mom says she worries about him because he rarely talks about what happened to Ramarley. She says when it first happened, he expressed hatred of police. Now, he just keeps it in. She worries that one day police will stop him too, and he’ll just “blow up on them.” She points out that Tamir Rice was not much older than Chinnor when police killed him. And he is her only boy now.

The day after the protest, Constance and her son (she also has a 26-year-old daughter; three years older than Ramarley would have been in April), are headed to Jamaica to bury her father. She is a palpably strong woman, but sometimes, her voice breaks, and her weariness is omnipresent.

The mayor’s office declined to comment directly, pointing to a May 3 press conference in which de Blasio was asked why he won’t meet with Constance.

“The broad standard we hold is once there is disciplinary action underway by an agency that I have ultimate responsibility for, it is not appropriate to meet with the family members. … Look, what happened to Ramarley Graham was obviously a tragedy and my heart goes out to the family. And there will be, because now the Justice Department has concluded its activities, there will be a disciplinary process by the NYPD and that has been made very clear to the Graham family.”

Constance Malcolm has no such clarity. To this day, no one in the NYPD has bothered to even apologize to her, for killing her son, who she says was friendly, and whose skin was so “smooth and dark” she called him “chocolate,” or for manhandling her mother and her. She says Mother’s Day and Ramarley’s birthday, which passed in April, are the hardest. She says the one thing that would ease her pain would be to know the officers who killed her son and, she believes, helped Richard Haste cover his legal backside, can never do to another person what they did to Ramarley.

“Right now that’s my only sort of justice, to get these officers fired,” she says. “Not just Richard Haste.” There’s more to her pain than who fired the fatal shot.