Twenty-one-year-old Stephen Silva stared at the court blankly as he identified his childhood friend, the defendant in the Boston Marathon bombing trial, Dzokhar Tsarnaev.

“He’s a person I would consider one of my best friends, back in the day,” he explained. At one point in time, he affectionately called the defendant, “Jizz.”

Prosecutor Aloke Chakravarty held up a photo of them in their black Cambridge Rindge and Latin graduation gowns, red carnations in their lapels, embracing.

Today was the first time the former friends had laid eyes on each other since early April 2013, no more than two weeks before the bombing. Despite his aloof demeanor, testifying was an experience his lawyer Jonathan Shapiro said his client found “weird” and “uncomfortable.” Silva told Shapiro they made eye contact. Tsarnaev appeared somewhat attentive to the testimony, but for the most part acted like he was in detention, per usual.

The last time the two met was in a Cambridge parking lot at Memorial Drive and River Street, near the apartment where Silva grew up.

By now, the jury is well familiar with the area. The apartment building, much of which is subsidized housing, marks a point of high-density population, among a neighborhood that mostly consists of one- or two-family housing. It overlooks both Shell and Mobil gas stations. The Shell station is where, after allegedly killing MIT officer Sean Collier, Tsarnaev stopped to pick up snacks, a regular blunt wrap and munchie haunt of his, according to Silva. It’s also where Dun Meng, the Tsarnaevs’ carjacking victim, made his daring escape. The Mobil station is where Meng hid and told the clerk to call the police.

Tsarnaev’s friend Robel Phillipos, who was convicted of lying to federal agents in the wake of the attack, grew up in that same building.

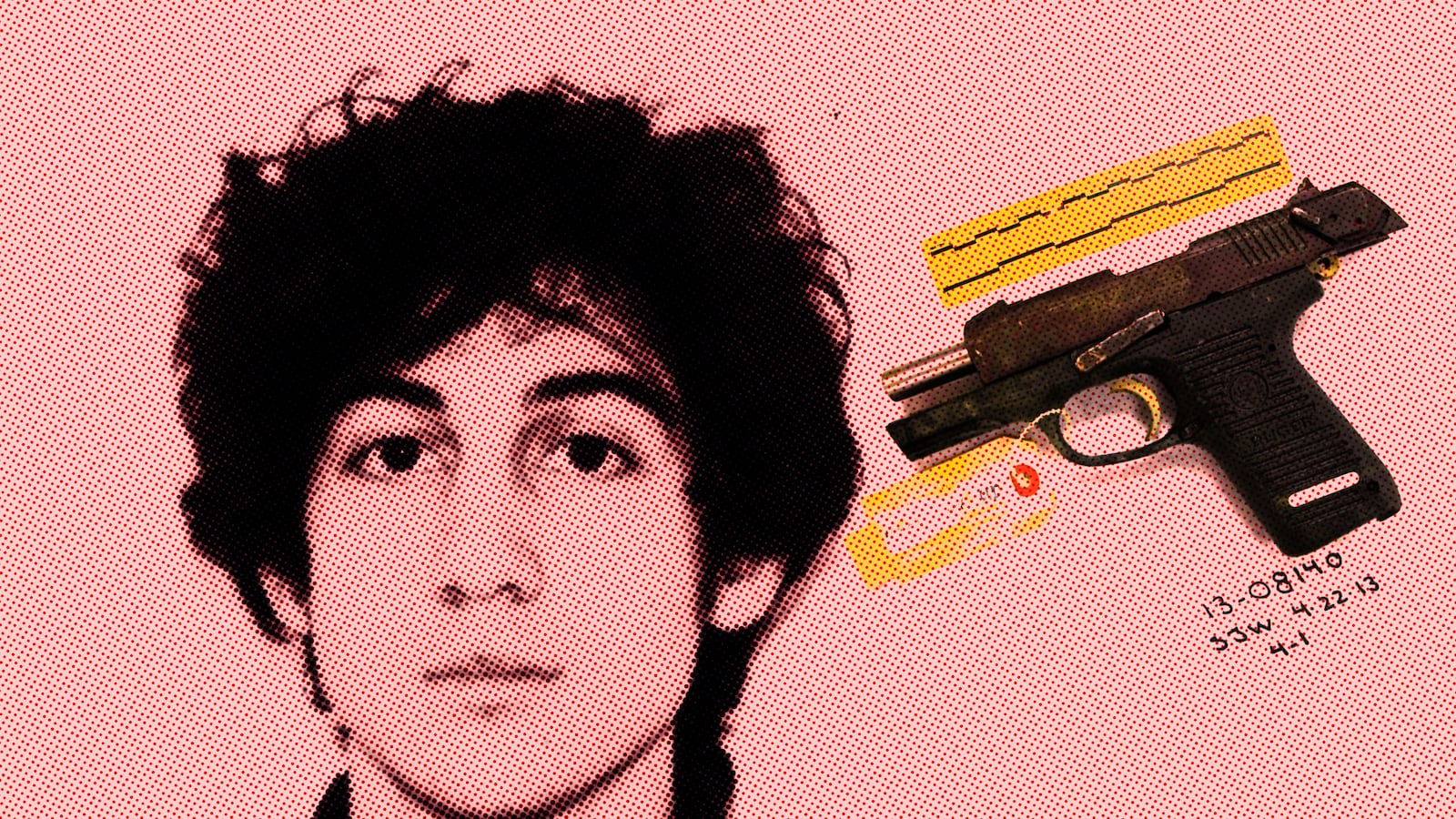

Back in early April, Tsarnaev returned to that very block to buy weed from Silva. Silva, in turn, was trying to get him to give back the rusty P95 Ruger pistol he lent him sometime in January or February.

Dzhokhar told Silva he needed the gun to “to rip some kids” from the University of Rhode Island. Or, in other words, to pull off a drug robbery.

But ever since then, Tsarnaev had been giving Silva excuses about why he couldn’t give the gun back. That day was no different. Silva was frustrated, but he couldn’t stay mad for long.

“I told the defendant I loved him,” recalled Silva. “And then I got out of the car.”

A lot has changed since early April 2013.

Silva’s testimony opened a new window into Tsarnaev’s terrifying spiral, from his outward appearance as a low-key Cambridge kid—enjoying blunts, burn cruises, and trips to a Swampscott swimming hole—to a terrorist on a murderous rampage.

But Silva’s life has fallen apart since the bombings, too.

Shortly after the bombing, using a pseudonym “Sam” (which was later exposed in court), Silva expressed his fear and confusion about his friend’s arrest to Rolling Stone magazine. He also said he feared feds were tapping his phone.

He wasn’t too far off.

Instead of tapping his phone, federal agents followed him using video surveillance with the assistance of an informant who was paid $66,000 for the help. One year after the bombing, on July 21, 2014, Silva was arrested for trafficking heroin and gun possession.

The next day, I found myself in the parking lot next to Silva’s apartment in the car with three of his friends while they rolled a blunt and watched TV crews flood the area around the building. News had just broken that Silva’s gun possession charges were linked to Tsarnaev.

“The whole hood was filled with cops. All downstairs was filled with FBI,” said Brian (whose real name is withheld) of the bust the night before.

The three young men agreed to speak to me on the condition of anonymity, and a trip to Popeye’s.

“Stephen doesn’t deserve this, fuck Jahar,” said a man who asked to be called Mike.

Silva didn’t know Tsarnaev was going to use the gun in a terrorist attack, and Mike thought the fact that he was linked to the bombing attack was unfair.

“He basically let him use it, but having no idea what he was going to do with it,” said Mike. “And next thing you know, he’s a terrorist.”

When Silva found out his friend was behind the bombing attack, Brian said he “was damn near depressed.” He describes Silva as an otherwise good kid.

“He smokes weed, he gets high, and he does his schoolwork,” he explained.

Silva admitted in court that he had been selling marijuana since he was 16 or 17 years old, and had even robbed a pair of drug dealers at gunpoint. But court documents show that after the bombing, he began to run even further afoul of the law.

When he was arrested in November 2013 at Boston’s JFK train station, he told police, “I smoke a lot of weed every day because my best friend was the bomber.”

“He was really just sad and depressed, surprised his friend Jahar would ever do this,” Mike explained.

Silva said as much to Rolling Stone. “His brother must have brainwashed him,” he said in 2013. “It’s the only explanation.”

Rolling Stone wrote that Silva “gratefully” received an anecdote, spread by one of his nurses, that Tsarnaev cried for two days straight in his hospital bed. “I can definitely see him doing that,” he said. “I hope he’s crying. I’d definitely hope ...”

Which brings us to the question: Whose witness is Silva anyways?

Officially, he’s the government’s witness. They are the ones who are brought him to the stand to testify, and who may potentially pave the path for a plea deal and leniency in his sentencing. Silva has already pleaded guilty to all charges and is facing a five-year mandatory minimum. He testified as part of a plea agreement with the government whereby minimum sentencing guidelines could potentially be lifted.

But ultimately, his testimony may best serve the defense.

This trial stopped being about whether or not Tsarnev carried out the bombing attack in the opening arguments when Judy Clarke, his own lawyer said, “It was him.” Instead, his attorneys are trying to argue that Tsarnaev, who was 19 years old at the time, acted under the influence of his now-dead older brother Tamerlan. The government in turn, is arguing that Dzhokhar was radicalized and carried out the attack by his own volition.

At first, Silva’s testimony seemed to work for the government. His story—that Dzhohkar, independently of his brother, obtained a gun and bullets that Dzhohkar called “food for the dog”—casts him in an active role.

Silva also recounted a high school class discussion about terrorism where Tsarnaev said, “American foreign policy tends to be a little hostile in the Middle East,” and that the U.S. was “persecuting Muslims” and “trying to take over people’s culture.”

Even more damning was a photo of Dzhokhar shown in court that Silva said was taken in the defendant’s bedroom. In the photo, the defendant appears pointing at a black flag, sometimes touted by Muslim extremists.

But in his earlier extensive interview with Rolling Stone, Silva seems to have planted the very seeds of the defense’s argument—that Dzhokhar was “brainwashed” by his brother.

Exactly how much of that argument was heard by the jury of that is unclear. Many of defense attorney Miriam Conrad’s questions were objected to by the government and sustained by Judge George O’Toole Jr.

But in nearly two weeks of testimony, and dozens of government witnesses (most of whom left the stand without cross-examination), Conrad was able to convey her argument about Dzhokhar’s relationship to his brother better through Silva than through any other conduit.

Silva, who had known Dzhokhar since middle school and hung out with him several times a week, had been to his house only once and had never met his older brother.

“Did he tell you, ‘You don’t want to meet my brother?’” Conrad asked.

“Yes, he did,” said Silva. “He said his brother was very strict, very opinionated, and since I wasn’t a Muslim he might give me a little shit for that.”

Conrad then suggested that maybe the reason Dzhokhar couldn’t return the Ruger was that his brother had it.

“Would you have loaned him the gun if he told you it was for his brother?”

“No,” answered Silva.