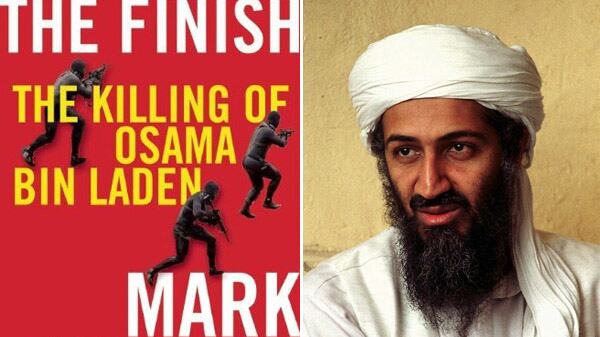

Mark Bowden’s The Finish is the first book, and, to date, the definitive one, that looks at the Osama bin Laden raid from President Obama’s perspective as he sat in the Oval Office debating how to continue the then-seven-year hunt for the al Qaeda leader. Bowden was granted rare access to the president to discuss the raid and to the strategic thinking that went into its planning at the White House, CIA, and Joint Special Operations Command. Bowden, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, has most famously written about U.S. Army intervention in Somalia in Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War (1999), Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar in Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw (2001), and cyberattacks and security in Worm: The First Digital World War (2011).

Aside from the human drama about the massive intelligence hunt for bin Laden, Bowden also draws a fascinating picture of then–Joint Special Operations commander Adm. William McRaven (McRaven is now commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command). The Finish is, as Bowden told me, “the story of two men, Osama bin Laden and President Obama. Essentially, the story is about Obama deciding to kill someone. The story is also about bin Laden deciding to kill many, and how these two men arrived at that point where they either had appropriated to themselves the authority to order someone’s death or had sought and been given that responsibility.”

In the 18 months since the killing of bin Laden on May 2, 2011, at least three other books have been published about the U.S. Navy SEAL raid that assaulted the Abbottabad, Pakistan, compound where bin Laden had been living. Of these books, No Easy Day remains the only eyewitness account—a fact that might change, says Bowden, as he suspects other SEALs may come forward to tell their stories. Bowden readily compliments the scholarship and reportorial scope of Peter Bergen’s Manhunt, which, like The Finish, takes a global, strategic view of the mission. This point of view sets these two books apart from No Easy Day and SEAL Target Geronimo, by former SEAL Team 6 member Chuck Pfarrer, the first book published about the raid (and a book I blurbed), which, Bowden says, he was told to avoid during his reporting. In varying degrees, these books offer different accounts—some slight, some large—about what actually happened that night.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Finish describes a new kind of war fighting—the fusion of intelligence from vast and scattered sources—to track and apprehend, or kill, the enemy. The Finish is as much about the hunt for bin Laden as it is about the complex—and unprecedented—hunt itself. It’s a gripping tale.

Doug Stanton: You’re about to start a national book tour. When someone asks what The Finish is about, what are you going to tell them?

Mark Bowden: [laughs] That’s the best of all questions. To me, the story of hunting down and killing Osama bin Laden is one of the major stories of the last decade in American life and in terms of our relationship with the world. I saw the story as being about the evolution of our war-fighting method beginning with 9/11, which dramatically reoriented our national defense structure and priorities, to the evolution of the means to defeat a new kind of enemy—and obviously Osama bin Laden symbolized that new kind of enemy. I think many of tactics and techniques that were developed to go after al Qaeda came into play in the hunt for bin Laden. So, in a way, the story of finding and killing him encompasses that larger story.

Within that, it’s also the story of two men, Osama bin Laden and President Obama. Essentially, the story is about Obama deciding to kill someone. The story is also about bin Laden deciding to kill many, and how these two men arrived at that point where they either had appropriated to themselves the authority to order someone’s death or had sought and been given that responsibility. What is the way that those two justify the decision that they make?

How is today’s world different from the world you wrote about in Black Hawk Down, which describes the 1993 battle in Somalia, during which it’s likely some members of al Qaeda participated?

So much is different. I think in 1993, the use of the U.S. military was largely focused on geography—on nation-states, and I think that the big question that the country faced in 1993, and still faces today, was, how should we use American power in a world where we, as a country, are not really threatened directly, but where we posses the most capable military force on the planet? Do we use that force to try to enforce broad ethical rules for civilization, like ending genocide or ending a famine, which is what we stepped in to do in Somalia?

I think the story of Black Hawk Down illustrated that the use of American force came at a price in lives, and that was something that had to be carefully weighed in the equation.

I think that since then, this capability of mounting significant attacks on the U.S. and our allies, in the case of hijacking commercial airliners and using them as guided missiles, you can see the potential for that to grow even more serious, and attacks being launched not by nation-states, but by global organizations linked through telecommunications and computer networks and who don’t have a home address. I think the difference between the early 1990s, when we were trying to figure out how to use how American force in a world where we were not personally or as a nation threatened, whereas I think, today, a threat has evolved that does matter directly to the American people. So, in a way, it’s a lot easier to make the case for going after al Qaeda than it was to intervene in Somalia, but the challenge is probably greater today than it was then.

Does that projection of military force today come with a price?

It definitely does come with a price—because the same tools and tactics that we employ against al Qaeda can be used against us. Right now, the U.S. has sort of cornered the market on drone technology, but drone technology is out there, and other countries will avail themselves of it. Just as in the past, it took a nation-state to manufacture and deploy WMD; I think that’s no longer the case. I think that capability is growing, even potentially beyond nation-states, and if you add into that the new capability of cyberattack, we are as vulnerable—shockingly vulnerable—as any other country in the world. And so if we were to bomb Iran’s nuclear facilities, we would pay a price. We would be counterattacked, I’m certain, probably through Hizbullah, perhaps through some sort of computer attack—I think we would pay a price. Which is not to say it’s never worth going to war, but it should be done with your eyes open, realizing that there will be a price to pay.

How did you get the idea for The Finish?

Clearly it’s something that would be of interest to me. I’ve written about Special Operations a lot over the last 10 years. But the truth is, I probably never would have undertaken it, because I have a disinclination to pursue the same stories that lots of other people are pursuing. In this case, it happened in a roundabout way. I was approached by a Hollywood producer, whom I’d worked with, who asked if I would research and perhaps develop a screenplay, which appealed to me because that was less a reporting challenge than it was a writing challenge, and I figured I could draw on the reporting that a lot of other really fine journalists would be doing in the coming months and years, in order to produce a screenplay.

But I decided that I would do some research myself, so I emailed Jay Carney, President Obama’s press secretary, and asked him to put me on the list of the thousands who were interested in interviewing the president and others at the White House about what had happened. This is literally the day after the raid.

And Jay, whom I’d gotten to know earlier when he was Vice President Biden’s press secretary [Bowden wrote a 2010 profile of Biden], and he wrote me back right away, and he said, “This sounds like a really cool idea,” and it wasn’t his decision to make, but as far as he was concerned, I would be somebody they would consider working with.

When the movie project didn’t proceed, and while I’d never intended to write a book, suddenly I had this prospect of remarkable access before me, so I called my publisher and said, “Would you be interested in a book about this if I can get this kind of access?”

Where were you on night of raid? Watching TV?

I was at my cousin’s house in Hermosa Beach, California, and I was sitting with my infant granddaughter on my lap, watching the Phillies-Mets game, and the crowd started chanting, “U.S.A., U.S.A!” And the game announcer said the president would be coming on in a few minutes and that apparently the U.S. had killed Osama bin Laden. And I remember only two times in my life watching TV where I was moved involuntarily to just stand up, because it was such a remarkable, wonderful piece of news. The first time was years ago when the Israelis successfully rescued the hostages at Entebbe airport in Uganda [on July 4, 1976]. I remember, as a kid, I was sitting in Baltimore watching TV, and this report came over, and I just stood up, and I thought, hooray, what a remarkable thing, and I felt exactly the same when I heard that Osama bin Laden had been killed. I stood up. I think the fact that I was holding my granddaughter is a big piece of why I felt the way I did, because I always view these terrorist organizations that are planning acts of mass murder as people who are trying to kill the people I love. It just felt very good to hear that news.

How did you report The Finish? What was most challenging?

For me, Doug, ordinarily my approach is to find the people most directly involved—in the case of Black Hawk Down, finding the soldiers who fought in the streets of Mogadishu and basically reporting from the ground up. In this case, because the news was so fresh, because the units are classified and off-limits, I really had no other way of approaching this story than from the top down. I find that very frustrating.

As nice as people were to me, the White House did not throw open all of it doors and files, as some people I’m sure will think is the case. It was extremely frustrating to get people on the phone, to get meetings scheduled. I remember asking about interviewing the president the day after the raid, and it took almost a year before I had a chance to do that. So there was a great deal of time spent trying to badger poor press aides for the secretary of defense, or the CIA director, or members of the president’s staff. It was frustrating, waiting and wondering if you were going to be able to get the kind of firsthand information that I need to tell the story the way I want to. It was a struggle [laughs], I have to say.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while talking with President Obama? How did the success of the raid affect him?

I think he feels, and he expressed, enormous satisfaction over it. While I conclude that the effort to find bin Laden was ongoing and probably would have proceeded pretty much the way it did, no matter who was president, I do think that the president feels, with some justification, that he very consciously made finding bin Laden a priority, a top priority. And in that sense, helped push things forward. And he may well have; you could go either way with that. But he definitely played a role bringing that mission into his office. And I think he’s proud, rightfully, of the careful way that decision was made. I think he took a risk, an enormous risk, not just to the SEALs on the ground, but to his reputation, his presidency, and legacy, and I think it paid off for him. It worked out about as well as you could hope.

I do think he’s been changed. I tried to document in the book the evolution of Obama’s thinking. I think he was someone who, early on—he’s a young man who, just 10 years before he was president, I don’t think he had given a lot of serious thought to the role and responsibilities for country to defend itself, for the president to make really tough decisions like these.

I think, like most people, he never imagined he would be in a position of making life-and-death decisions, quite literally, over individuals, on an almost daily basis. And yet I think he’s evolved a very careful, kind of ethical, framework in which he comfortably accepts the responsibility. I don’t think he’s the kind guy who has a lot of misgivings afterwards. He might have some misgivings about what some people on his staff blurt out to the press, but I think he feels very good about accomplishing this.

This goes back to his strategic philosophy that was, it was a mistake to invade Iraq—the use of large numbers of conventional forces causes as many problems as it solves. The right enemy was not terror, but the people who attacked us on 9/11, al Qaeda. I think this was a capstone to the major military project of his term.

How important is the death of bin Laden to President Obama’s agenda to disrupt and dismantle al Qaeda?

I think it’s tremendously important. I do think that the formal organization called al Qaeda is basically gone. [Al Qaeda leader] Ayman al-Zawahiri is still out there, but as a functional organization, the group that planned and executed the attacks on 9/11 has been effectively destroyed. I think the death of Osama bin Laden was the symbolic end—that’s one of the reasons the book is called The Finish—of that episode. That’s not to say that the franchise of al Qaeda will not live on, in these local groups who fly that flag, as we saw recently in [the attack in] Benghazi, Libya. We’ll be dealing with people who call themselves al Qaeda for a long time to come. But none of these organizations that call themselves al Qaeda are truly international. They’re not capable of pulling off something like 9/11. There are terror organizations—I think Hizbullah is one—that are capable of that kind of stuff, but if I think if the goal was to defeat al Qaeda, then the death of Osama bin Laden really sealed the deal.

Having said that, I think it was also significant, psychologically, for the country. Because I think the attacks of 9/11 remain a kind of open wound in this country, and the fact that the person who orchestrated them was still at large was a kind of daily insult to the American people. And I think to the extent that governments can maintain the illusion there is justice in the world [laughs], this was an important step in that direction.

Did you know that the book No Easy Day, by former SEAL Team 6 member “Mark Owen,” was being published?

I didn’t, actually. I talked to Matt Bissonette [true name for author Mark Owen] months ago, in my efforts to get members of that team to talk with me, and so I’d had long discussions with him before he left the unit, where he was trying to make up his mind what he was going to do. Obviously, one alternative was for him to go out and get a big payday to do his own book. I did my damnedest to argue that he ought to instead work with me. He was much too smart for me. I wasn’t able to talk him into it. But I was surprised that they put that book out as quickly as they did. In fact, Matt called me toward the end of last summer, and he asked me when my book was coming out. And I was still of the mindset that we were still discussing the possibility of him letting me interview him. So I told him, “Well, as of right now, I think my publisher is trying to get this book out during the election season.”

At this point, the phone connection between Stanton and Bowden goes dead. When it resumes, Bowden asks, “Where did I get cut off?”

Matt Bissonette had asked you when your publication date was.

Yeah, I thought that was a little cheap. I would have told him if he just asked me (and told me) why he wanted to know. And it was a little cheesy, I think, to name himself Mark Owen, which is just two little letters away from Mark Bowden, but I figure that’s sort of flattery [laughs]. So I’ll take it as that. And I think in the stampede of people to buy his book, some will now accidentally buy my book [laughs].

One of the books you acknowledge in your notes is Peter Bergen’s Manhunt. You’re a fan of that book?

I think Bergen is a terrific reporter. He did an amazing job. You know, I was pissed off reading it, because there was all this material that I had worked very hard to get, and because I’m a slower worker than him, I realized, shit! It’s all in there. Peter just did a fantastic job. To be honest, I benefited by having read Manhunt, and I benefited by having read the other works he’s written about bin Laden. I admire him as a reporter. And the book by Matt Bissonette was fascinating because it’s the only firsthand account of the raid. It corroborated a lot of things I had learned about the basic structure of the mission and how it unfolded. And it also added some things that I didn’t know and corrected one or two pieces of misinformation.

To be honest, I hope he sells a million copies. I honestly think he is an American hero. Here’s a guy who spent 10 years fighting these wars, and if anybody deserves to sell a lot of books, it’s him. I wish him well. I’m glad to have had the input [of his book]. I would rather have had it directly myself, but I completely understand why he did it the way he did. I think you’re going to see that there will be other SEALs now who will come forward and who will offer slightly different versions of what actually happened. And we may be in for a very tawdry struggle between a couple of different SEALs who claim to really be the guy who killed bin Laden [laughs]. Somebody said to me, “We think of them as this macho fraternity. In some ways, they’re really a lot more like a sorority.”

Accounts about the raid vary in describing when, exactly, bin Laden was shot. What did you discover in your research?

I’ve heard two different versions of those final moments. My understanding is that there were three SEALs who went up those stairs. Bissonette places himself second in line. I know another SEAL who claims to have been in front of Bissonette. There was a lead guy, and the lead guy did shoot at bin Laden when he peeked out of the room—whether he hit him or not, I don’t know for certain. I know they chased him into the room. The lead SEAL tackled the women [in the room] and got them out of the way. The fact that the one wife was hit says to me that there were bullets flying. So more than one person was firing.

So, was bin Laden hit by the first guy and then fell over backwards into the room? Was bin Laden not hit by the first guy and then shot in the head by the second guy? I do think that what Bissonette says is true—I think he entered the room and he pumped some bullets into his chest, and that by the time he was pumping bullets into his chest, bin Laden had already been shot in the head. But what I’m not absolutely certain on is whether that shot came from the first guy or the second guy. And from what I’m told, you will never hear a peep from the first guy, who is just, apparently, a SEAL’s SEAL, and who will never breathe a word to anyone about any of it.

But you are likely at some point, I predict, to hear from the second guy, and the second guy might well make the claim that he is the person who shot bin Laden in the head. And then Bissonettte comes in after, possibly with yet another SEAL, and they pump bullets into his chest. You know what? I think the truth is that it just doesn’t matter all that much anymore. I think the reason there are these disparities, as you well know, is that you talk to five people and there are five slightly different versions of the events. I would emphasize that these are all slightly different versions of events and very well may be readily justified, if that’s the right word. I think that what actually happened probably happened really fast. It doesn’t necessarily mean that somebody’s lying. It just could mean “That’s what I remember happening.”