During the presidential campaign, Donald Trump liked to invoke his late uncle, MIT research scientist John Trump, as evidence of the family’s exceptional gene pool, proof should voters need it that Donald Trump is smart, like really smart.

“It’s in my blood,” he says.

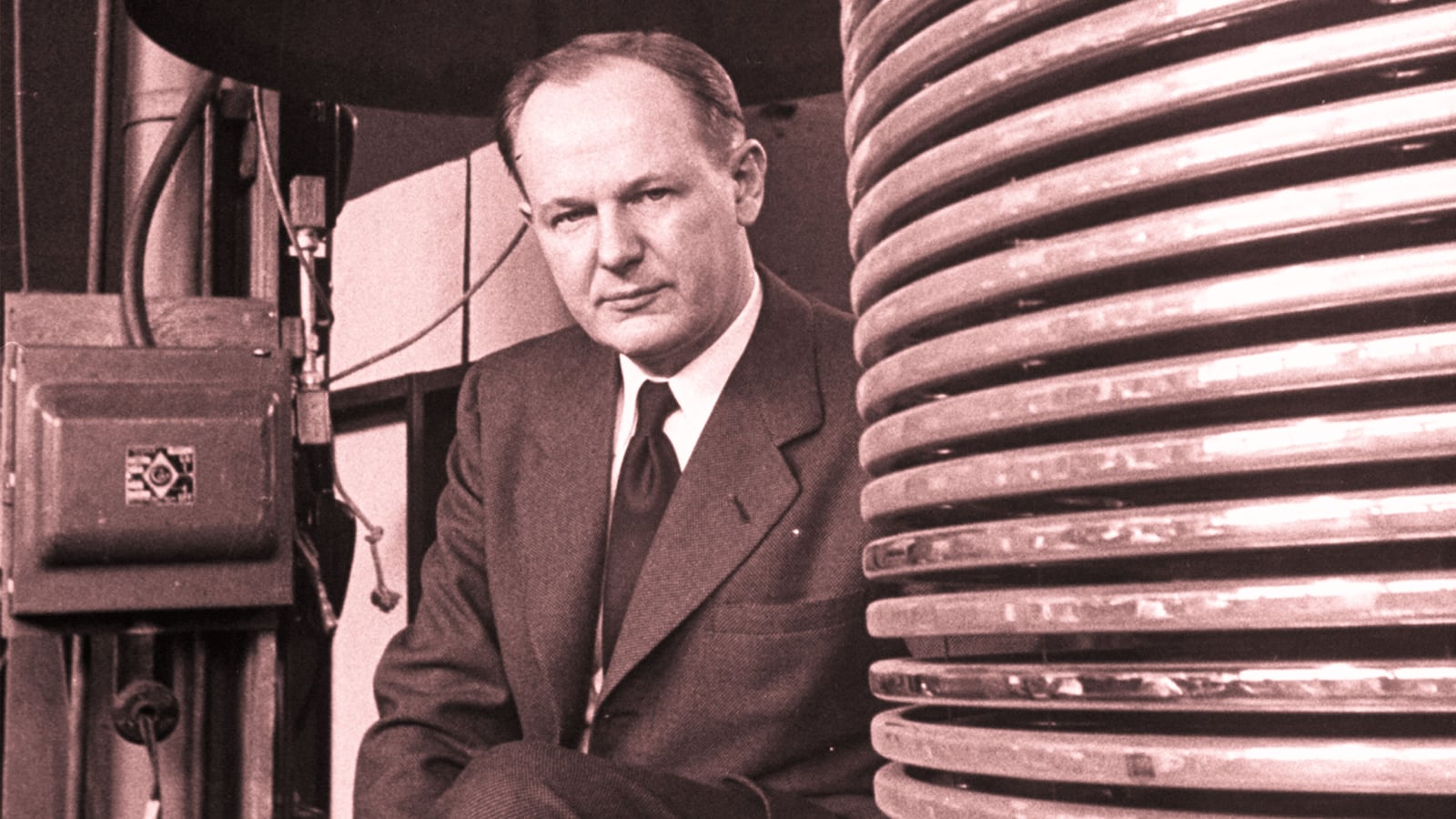

He called John Trump a genius, and he’s right about that. President Reagan awarded John Gordon Trump the President’s Medal of Science in 1985 with this citation: “For his introduction of new machines and methods for the widespread beneficial application of ionizing radiation to medicine, industry and atomic physics.”

John’s son accepted the award. His father had died at age 77, just days before. Eighteen other scientists were honored in a ceremony at the White House, and Reagan joked that they enjoy their work so much “they almost feel guilty getting paid for it.” Reagan credited his budget director, Dave Stockman, for feeding him that line. It got a big laugh. Stockman was well known for his slash-and-burn approach to government spending.

“Well, we’re not here to take up a collection,” Reagan said, pointing out that despite the constraints on federal spending, his budget for the next fiscal year called for a 6.7 percent increase in basic research in the physical sciences. He went on to deliver a testimonial for scientific knowledge as the “ultimate source of innovation, of new technology, of human progress itself.”

That event more than 30 years ago should shame Donald Trump, whose budget calls for an 11.2 percent cut in the National Science Foundation, the federal agency that supported his renowned uncle’s work. The NSF will only be able to fund about 19 percent of the research grant proposals that scientists submit, down from last year’s 21 percent. Francis Collins, head of the National Institutes of Health, said in 2015 that scientists face the worst funding environment in 50 years, a crisis that President Trump’s budget would worsen.

John Trump made his name as a war-time scientist and when Paris was liberated, he rode with General Eisenhower into the city, where he set up a branch of MIT’s Radiation Lab before returning to the MIT campus in Boston, where he would spend 35 years. His lab director, James Melcher, said in a memorial tribute that “John over a period of three decades, would be approached by people of all sorts because he could make megavolt beams of ions and electrons – death rays. What did he do with it? Cancer research, sterilizing sludge out in Deer Island (a waste-disposal facility), all sorts of wondrous things. He didn’t touch the weapons stuff.”

Donald Trump mostly talked about him in the context of his nuclear expertise. “My uncle used to tell me about nuclear before nuclear was nuclear,” he boasted during the campaign, suggesting he got the hot skinny on the hydrogen bomb before it was publicly known, and that his uncle conveyed to him that this would be something very bad.

He told CNN’s Anderson Cooper that he hated nuclear weapons more than anything. But then he went on: “Can I be honest with you? It’s going to happen, anyway. It’s going to happen anyway. It’s only a question of time… Now, wouldn’t you rather in a certain sense have Japan have nuclear weapons when North Korea has nuclear weapons?”

For world leaders and average Joes trying to decipher where Trump is on nuclear proliferation, good luck. On the one hand, he thinks these weapons are terrible (who doesn’t?). On the other hand, he seems to endorse the policy known as MAD, for Mutually Assured Destruction.

Maybe the commander-in-chief is just a fatalist and thinks what will be, will be. His father died at age 93 after spending his last decade in the throes of Alzheimer’s disease. Trump says a lot of what he admires in himself he got from his father, and when asked if he worries that Alzheimer’s could claim him too, he says no.

“Do I accept it? Yeah,” he said. “Look, I’m very much a fatalist.”

In the account of Fred Trump’s wake at the prestigious Frank E. Campbell funeral home in Manhattan, Trump closed out his father’s life before a New York crowd of movers and shakers, with these words. “My father taught me everything I know. And he would understand what I’m about to say,” he told the mourners. “I’m developing a great building on Riverside Boulevard called Trump Place. It’s a wonderful project.”

John Trump was Fred’s younger brother by two years, and when their father died in the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, their mother founded Elizabeth Trump & Sons. It soon became apparent that the brainy younger son did not have a calling for real estate, and John went off to MIT, where he became a full professor and director of MIT’s High-Voltage Research Laboratory from 1946 to 1980.

He launched his last major project with grants from the National Science Foundation in 1974 ($581,700) and 1977 ($312,159) to investigate whether millions of gallons of raw sewage dumped into the Boston harbor could be treated with energized electrons to separate out PCBs and other deadly compounds and make them less noxious. He is credited along with his associates with building the prototype at the Deer Island Sewage Plant in Boston Harbor.

His nephew never talks about that, maybe because cleaning up sewage and sludge is not as sexy as working on nuclear weapons, or curing cancer. The two did share what can be called a Trumpian energy and drive.

“Trump’s remarkable personality mix contributed to all of this achievement and success,” according to a tribute in Physics Today.

That line could be applied to President Trump as well, but the similarity ends there. The article about John Trump concludes, “He was remarkably even tempered, with kindness and consideration to all, never threatening or arrogant in manner, even when under high stress. He was outwardly and in appearance the mildest of men, with a convincing persuasiveness, carefully marshalling all his facts.”

That is not the Trump we know today.