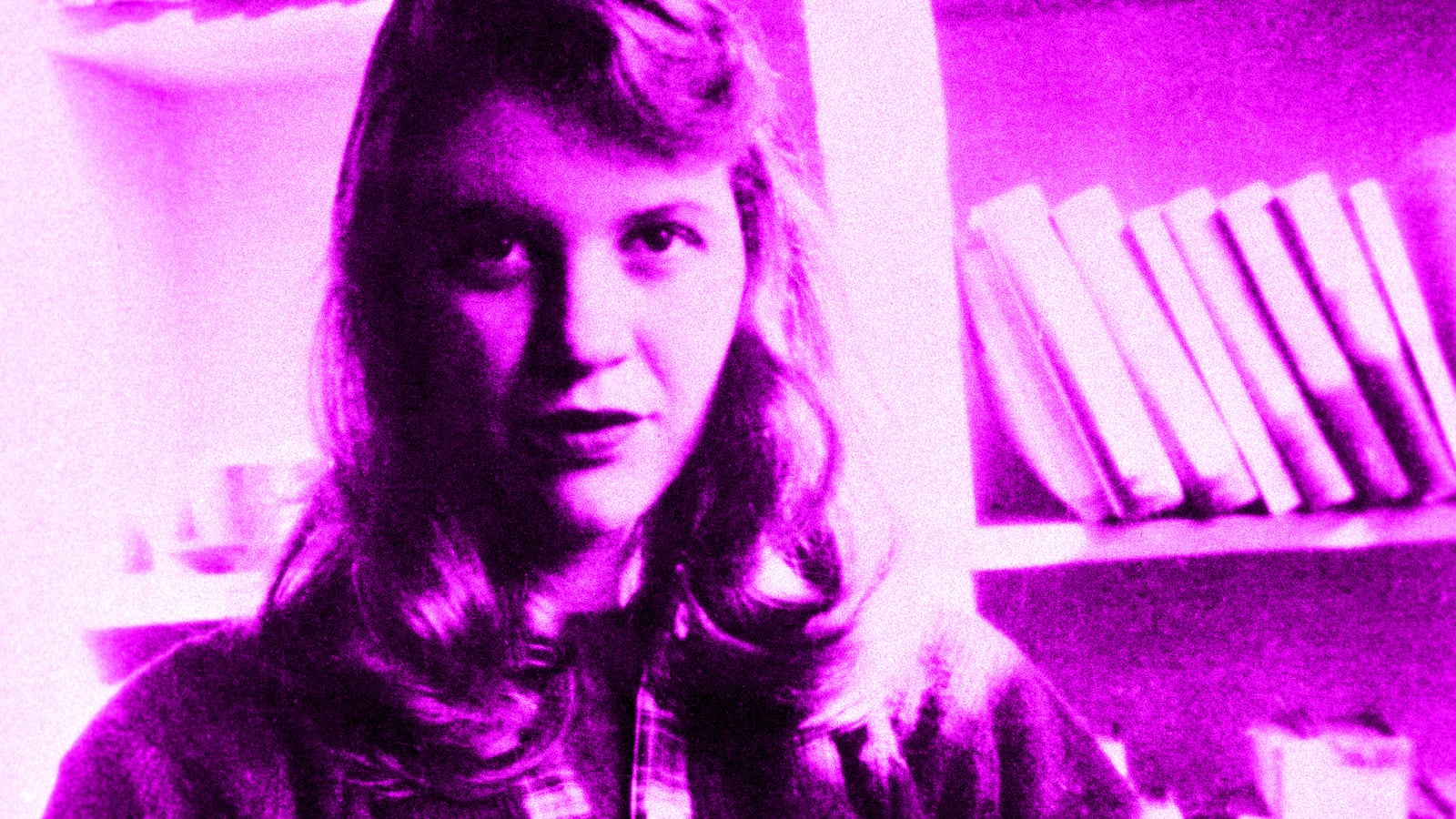

At the time of her death in 1963, Sylvia Plath had only published two works: one book of poetry, which hit the stands in 1960, and one novel, The Bell Jar, which had been released the previous month, and then only in the UK. A second book of poems, Ariel, was published posthumously by her estranged husband, Ted Hughes.

Despite this dearth of published works, Plath, who committed suicide aged 30, left behind a trove of writings—journal entries, short stories, poems, and other documents—that have helped fuel the interest in her life and work that only seems to grow with the years.

Not only do academics continue to analyze every turn of phrase of the writings that remain, but there is a constant search to discover more of her work, to create a better understanding of the genius and tragedy of a writer gone just as she was starting to find her voice.

In just the last five years, scholars have published new works on unexamined—and previously unknown—aspects of her legacy including her prolific drawings, unpublished letters, and newly discovered poems.

But while the hope for new finds continues unabated, one known text eludes all who seek it. In the summer of 1962, Plath began work on her second novel. We know what it was about—a fictionalized autobiography in the vein of The Bell Jar about an artist who discovers her husband has cheated—and we know that she completed a number of pages of the book before her death. But in the years that followed, the manuscript for Double Exposure vanished.

“The importance of this novel cannot be overstated,” Gail Crowther, co-author of These Ghostly Archives: The Unearthing of Sylvia Plath, wrote in an email to The Daily Beast. “We know that Plath rated it highly (in contrast she referred to The Bell Jar as a ‘potboiler’) and it was her aim to write a novel and sell the film rights so she could raise enough money to buy a house in London.”

The book was coming at a crucial moment in Plath’s life. Plath had met Hughes at a party in Cambridge while she was studying on a Fulbright scholarship. Their love was almost instant, characterized by the immediate passion and infatuation that only seems real in novels. Four months later, they married.

“O Teddy, how I repent for scoffing in my green and unchastened youth at the legend of Eve’s being plucked from Adam’s left rib; because the damn story’s true; I ache and ache to return to my proper place, which is curled up right there, sheltered and cherished,” Plath wrote in a letter to Hughes on October 7, 1956.

The literary power couple eventually settled down in the English countryside, had two children, and dedicated themselves to their work. ''We would write poetry every day,'' The New York Times quotes Hughes as saying. ’'It was all we were interested in, all we ever did. We were like two feet, each one using everything the other did.''

But in the summer of 1962, things started to fall apart. Unhappy in the English countryside of Devon, Plath also discovered that her husband was having an affair. At the end of the summer, the couple separated and Plath moved to London with the children.

The affair was a devastating blow to her personal life, but it gave Plath a burst of inspiration. Many of the poems in Ariel were written following her separation and explored this aspect of her life. And then there were her plans to use this traumatic experience as the basis of her second novel.

On August 10, 1962, Plath wrote an urgent reminder in her calendar: “Start Int. Loaf!!!” (The Interminable Loaf was the first name of the book. Plath would change it to DoubleTake before settling on Double Exposure.)

We know that Plath did start the book, although reports on her progress vary. In the introduction to Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, a collection of Plath’s journal entries, short stories, and journalism, Hughes writes, “After The Bell Jar she wrote some 130 pages of another novel, provisionally titled Double Exposure. That manuscript disappeared somewhere around 1970.”

But Crowther says Hughes cited the number of pages at around 60 to 70 in other accounts, and his sister Olwyn once wrote in a letter that only two chapters had been finished.

Several Plath associates report reading portions of it—and sometimes reveal their reactions (Hughes’s mistress, Assia Wevill, was allegedly “appalled” at how the characters based on her and her husband were portrayed). Author and poet Judith Kroll reports having seen an index card with a chapter-by-chapter outline of Plath’s plan for the book.

Plath herself was thrilled with her progress. On October 12, in a letter to her brother, she wrote, “My stuff makes me laugh & laugh, & if it can make me laugh now it must be hellishly funny stuff.”

But these bits and pieces of Double Exposure give us only a glimpse of the writing that once—and may still—exist.

When it comes to her formal writing, Plath is primarily regarded for her poetry, but she herself held novelists in higher regard.

“How I envy the novelist,” she wrote in an essay in 1962. “If a poem is concentrated, a closed fist, then a novel is relaxed and expansive, an open hand: it has roads, detours, destinations; a heart line, a head line; morals and money come into it.”

Plath's poetry is visceral and powerful, and her journals and essays provide incredible insight into how the writer saw the world and then digested those observations into poetry and fiction. But to have a second novel of Plath’s, a second work in the format she regarded most highly, is a tantalizing prospect.

“It is interesting that she draws attention to the humor in the novel and this certainly corresponds to the fragments of Journal entries that exist from the same period,” Crowther says. “She kept notes on several of her Devon neighbors and her observations are some of her funniest, sharpest ,and wittiest work. To see this play out in a novel would be pretty powerful, I think.”

But despite the desires of Plath scholars, Double Exposure remains “maddeningly elusive.”

Hughes claimed both that the manuscript went missing after 1970 and that Aurelia Plath, Sylvia’s mother, was the last to possess it, although none of his claims have been verified. Because they were still married at the time of her death, Hughes became the executor of Plath’s literary estate and he is known to have burned at least one journal, her last, “to protect their children.” And then there is the rumor that Smith College may have a secret copy stashed away in their archives.

While these rumors haven’t helped scholars get any closer to locating the missing second novel, that doesn’t mean all hope is lost. After all, unknown poems and journals of Plath’s continue to be discovered.

“The current situation is that the manuscript is ‘missing’ but may still presumably turn up,” Crowther says. “Everything we know about this novel can only be pieced together via secondary sources—we see glimpses here and there, but nothing substantial. It remains rather ghostly.”