In Tonight We Bombed the U.S. Capitol: The Explosive Story of M19, America’s First Female Terrorist Group, historian William Rosenau tells the true story of a homegrown band of violent extremists who waged a self-declared war on their own country during the ’70s and ’80s. On the evening of November 7, 1983, an explosion rocked the U.S. Capitol. The bomb, which went off on the building’s second floor, caused an estimated $1 million in damages. And while no one was killed or injured, a communiqué issued later by the group that claimed responsibility for the attack suggested that the outcome could have been far different: “We purposely aimed our attack at the institutions of imperialist rule rather than at members of the ruling class and government. We did not choose to kill any of them at this time. But their lives are not sacred and their hands are stained with the blood of millions.”

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan announced that it was “morning in America.” He declared that the American dream wasn’t over—far from it. But to achieve that dream, the United States needed to lower taxes, shrink the size of the federal government, and flex its military muscles abroad. Some called his program the Reagan Revolution.

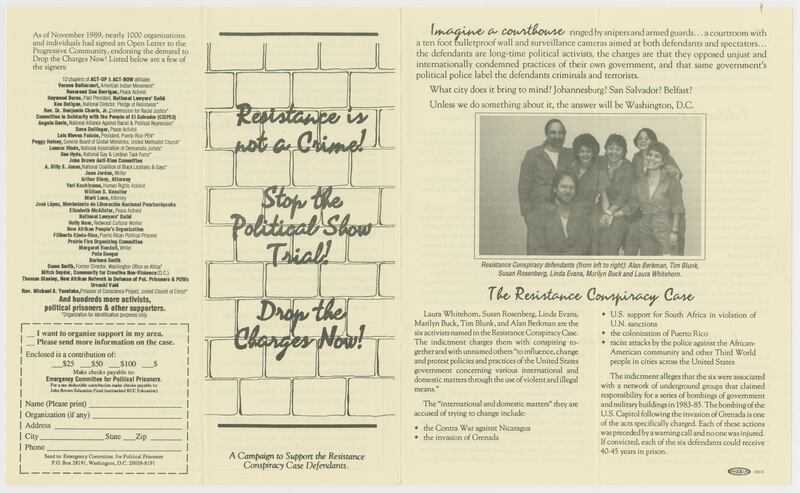

Meanwhile, a tiny band of American- born, well-educated extremists were working for a very different kind of revolution. They’d spent their entire adult lives embroiled in political struggles: protesting against the Vietnam War, fighting for black, Puerto Rican, and Native American liberation, and fighting against what they called U.S. “imperialism”—that is, U.S. military aggression, political domination, and economic exploitation, particularly in the Third World.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many of them had been close to, or involved in, the violent far-left scene during the late ’60s and early ’70s. They were part of the so-called Generation of 1968, a worldwide cohort that embraced drugs, sex, rock music, and revolutionary politics with equal enthusiasm. “In the 1970s, a militant revolutionary ethos took hold in a substantial part of the American counterculture,” wrote journalist Jeffrey Toobin. “To a degree that is almost unimaginable today, the bomb became a common mode of American political expression.”

The Weather Underground Organization was among the most notorious elements in this extremist scene. An offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)—possibly the largest left-wing student group in U.S. history—the Weather Underground, inspired by Third World revolutionaries, sought to foment domestic insurrection and confront U.S. imperialism from the inside, and with force. In an early manifesto, Weather declared that “We are within the heartland of a world-wide monster, a country so rich from its world-wide plunder that even the crumbs doled out to the enslaved masses within its borders provide for material existence very much above the conditions of the masses of people of the world.” What was needed, Weather said, was the “destruction of US imperialism and the achievement of a classless world: world communism.”

“We’re tired of tiptoeing up to society and asking for reform,” said Bill Ayers, a leader of the Weatherman faction. “We’re ready to kick it in the balls.” By the mid-’70s, Weather had taken credit for dozens of bombings of government and corporate buildings.

Women were part of Weather—they were founders, they were members of its ruling Central Committee (also known as the “Weather Bureau”), and they were cadres in its underground cells. But while the group supported women’s liberation in theory, Weather’s largely male leadership was different in practice. The group’s “Smash Monogamy” campaign, ostensibly designed to shatter repressive sexual paradigms, created new opportunities for male erotic aggression and domination. Weather Bureau member Mark Rudd, a leader of the SDS uprising at Columbia University in 1968, confessed in his memoirs that the campaign “meant freedom to approach any woman in any collective. And I was rarely turned down, such was the aura and power of my leadership position.”

Members were often subjected to hours-long “criticism/self- criticism” sessions, and these blistering collective critiques were often directed at women who Weather males saw as particularly headstrong and independent. Susan Stern, a former Weather member, recalled a five-hour session in which she was charged with being “individualistic, egotistical, self-centered, power- hungry, manipulative, monogamous, dope-crazed, sexually perverted, dishonest, counterrevolutionary and arrogant.” Weather took a hard line on motherhood—women who appeared overly devoted to their babies were reprimanded for a purported lack of revolutionary commitment. And in some cases, children were taken from their mothers and given to other members of the group so they could refocus their energies on the cause.

By the late ’70s, Weather was defunct. Most of the leadership, exhausted from nearly a decade on the run, surfaced from the underground, and those wanted on criminal charges surrendered to the authorities. Ultimately, Weather’s clandestine enterprise had been a failure, wrote the journalist Bryan Burrough. The group had “failed to lead the radical left over the barricades into armed underground struggle; failed to fight or support the black militants they championed; failed to force agencies of the American ‘ruling class’ into a single change more significant than the spread of metal detectors and guard dogs.”

Many other Vietnam-era radicals also called it quits and returned to graduate school, started careers, and reentered ordinary American life. One left-wing militant observed that a lot of her comrades “had already stopped being active or said they wanted to check out doing other kinds of (non-revolutionary) political work. To me it looked like that choice led to becoming ‘yuppies,’ professionals and arm-chair activists.”

But pockets of militancy remained. In certain parts of New York, the Bay Area of California, Chicago, and Austin, Texas, a revolutionary sensibility “still smoldered and sparked,” as one participant recalled. One of these militants characterized herself as “totally and profoundly influenced by the revolutionary movements of the sixties and seventies.” The Weather Underground was gone, but she and just a few others vowed to continue the struggle and to do so by any means necessary.

“We lived in a country that loved violence,” she said. “We had to meet it on its own terms.”

In 1978, some of the militants created a new organization to wage a war against imperialism, racism, and fascism. They derived the group’s name from the birthday shared by two of their ideological idols, Malcolm X and Ho Chi Minh: the May 19th Communist Organization.

May 19th was unique—unlike any other American terrorist group before or since. May 19th was created and led by women. Women picked the targets, women did the planning, and women made and planted the bombs. They’d created a new sisterhood of the bomb and gun.

To outsiders, these people must have seemed like ideological robots programmed for permanent rebellion. Like ghosts visiting from the past—unfriendly reminders of the ferocious struggles that had threatened to tear the country apart in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

May 19th certainly didn’t see itself that way. Its members weren’t automata, relics, or spooks but agents of history willing to sacrifice everything to transform the world. May 19th members prided themselves on their psychological toughness, analytical rigor, and lack of sentimentality. They were intellectuals but also warriors, with the purported science of Marxism- Leninism serving as their infallible guide. As Marxist-Leninists, they believed that men and women could bend the arc of history and usher in a new world free of injustice and oppression.

Their vision of what this heaven on earth would look like was hazy, but one thing was certain: creating it would require nothing less than violent revolution. This vagueness about ultimate objectives is typical among terrorists. As Georgetown University’s Bruce Hoffman argued, groups as varied as al-Qaeda and the Red Army Faction “live in the future they are chasing after, [but] they have only a very vague conception of what exactly that future might entail.”

May 19th had much in common with other ideological extremists. In her book True Believer: Stalin’s Last American Spy, the author Kati Marton wrote that Soviet agent Noel Field’s “commitment and his submission to his cause were as total, and ultimately as destructive, as those of today’s ISIS recruits.” Ideologies—whether communist, fascist, nationalist, or jihadist—can offer the promise of what Marton calls “a final correction of all personal, social, and political injustices.” For the captured minds of May 19th, their variant of Marxism- Leninism was a pathway to total liberation. As another of their ideological heroes, Fidel Castro, said in 1961, “Dentro de la revolución, todo; contra la revolución, nada” (“Inside the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing”).

Most of the members of the group were self-described lesbians, and they were feminists, but they weren’t part of the bourgeois women’s liberation scene represented by Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and the National Organization for Women. Pay equity, day care, abortion rights—all well and good, but in May 19th’s view, they were secondary to the real struggle at hand.

During the ’70s, some radical feminists insisted that “testosterone poisoning” had saturated American life. Total separation from “parasitic male mutants,” as one writer put it, was the only way to escape systemic male domination, violence, and aggression. “This is the year to stamp out the ‘Y’ chromosome,” one lesbian collective insisted in 1973.

Thousands of women built penis-free enclaves in cities around the country—the Gutter Dykes in San Francisco; the Furies in Washington, D.C.; and C.L.I.T. (Collective Lesbian International Terrors) in New York. The Van Dykes, a peripatetic band of motorized vegans, roamed southwestern highways in search of an imagined “Womyn’s Land.” Lamar Van Dyke, the group’s founder, was “a kind of lesbian Joseph Smith,” who, like the founder of Mormonism, traveled with an entourage of “wives and ex-wives and future wives in tow.” In New York, the Radicalesbians collective—known originally as Lavender Menace, a name chosen in reaction to Betty Friedan’s remark that lesbians were a “lavender menace” that threatened the women’s liberation movement—declared, “A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.”

The women of May 19th couldn’t have agreed more. But for them, “explosion” wasn’t just a metaphor. They channeled their fury into violent insurrection. They took in the words of Leila Khaled, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (and a purported Audrey Hepburn look-alike), who became a global revolutionary icon after her participation in an August 1969 airline hijacking. “We act heroically in a cowardly world to prove that the enemy is not invincible,” she declared. “We act ‘violently’ in order to blow the wax out of the ears of deaf Western liberals and to remove the straws that block their vision. We act as revolutionaries to inspire the masses and to trigger off the revolutionary upheaval in an era of counterrevolution.”

May 19th hated sexism, chauvinism, and misogyny, but its members weren’t interested in the crunchy, women-only lifestyle embraced by the separatists. As one woman close to May 19th explained, “I think it was a reaction to… lesbian separatism, and being like, oh, if we just go back to our own land, and leave men out of our lives, then everything will be fine, and we can just wear our Birkenstocks, and have our women-only spaces, and live our own lives.”

For May 19th, revolutionary politics came first. Sexual oppression, capitalism, racism, imperialism—all of that horror went together. Lesbian liberation required national liberation.

Men would be allowed to join the struggle, provided they were tuned in to the correct ideological frequency. Men could be useful in all kinds of ways—one male member even donated his sperm to a female comrade who wanted to have children. But they had to know their place and be alert to and fight against any sexist or homophobic proclivities.

In 1979, just after May 19th’s founding, the Talking Heads released “Life During Wartime.” Reportedly inspired by accounts of terrorist groups such as the Red Army Faction and the Symbionese Liberation Army, the song is a driving, hallucinatory first-person chronicle of a hunted, unnamed figure moving through an unspecified underground realm: “Heard of a van that is loaded with weapons/Packed up and ready to go.” May 19th lived the band’s lyrics, and in real time.

Typically, Americans see terrorism as something alien, foreign, and rare. But violent political extremism is woven deeply into our history. Consider the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans from the 16th through the 19th centuries; the counterrevolutionary terrorism carried out by white southerners during the era of Reconstruction; violent acts committed by (or attributed to) anarchists, including the bombing outside J.P. Morgan’s bank in lower Manhattan on September 16, 1920, that killed 39 people and wounded hundreds of others—“the day Wall Street exploded,” Yale historian Beverly Gage called it.*

And sedition and armed insurrection by white supremacists during the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, which culminated in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on the morning of April 19, 1995 and killed 168 people (including 19 children) and injured hundreds.

The U.S. government defines “domestic terrorist” acts as those that “occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.” “Homegrown” terrorism has its own definitions. The journalist and counterterrorism expert Peter Bergen, in an article written just after the June 12, 2016, Orlando nightclub massacre, noted that “every lethal terrorist attack in the United States in the past decade and a half has been carried out by American citizens or legal permanent residents, operating either as lone wolves or in pairs, who have no formal connections or training from foreign terrorist organizations.” In other words, these attacks were by homegrown terrorists.

The women of May 19th were part of a generation of violent left-wing militancy in the United States that stretched from the ’60s into the ’80s. Uncovering the history of the group can help us understand how and why a tiny band of Americans decided to wage a war against their own country. That history isn’t likely to produce tidy “lessons” about how such terrorism can be prevented, but it can help us understand the circumstances and contexts from which homegrown domestic terror emerged, and make us better prepared to grapple with the violent political extremism that remains part of the American landscape. After all, as the Black Power militant H. Rap Brown said in 1967, “violence is as American as cherry pie.”

Excerpted from TONIGHT WE BOMBED THE U.S. CAPITOL published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2020 by William Rosenau.