Although many patriots die on battlefields, the Reverend Thomas Starr King may be the rare patriot who died on the speaker’s circuit.

President Abraham Lincoln considered King the man most responsible for keeping California in the Union. King also helped keep California free and united defying pro-slavery Southern Californians threatening to bolt. Giving the small, sickly King an audience and a cause roused him. “Though I weigh only 120 pounds,” he acknowledged, “when I’m mad, I weigh a ton.”

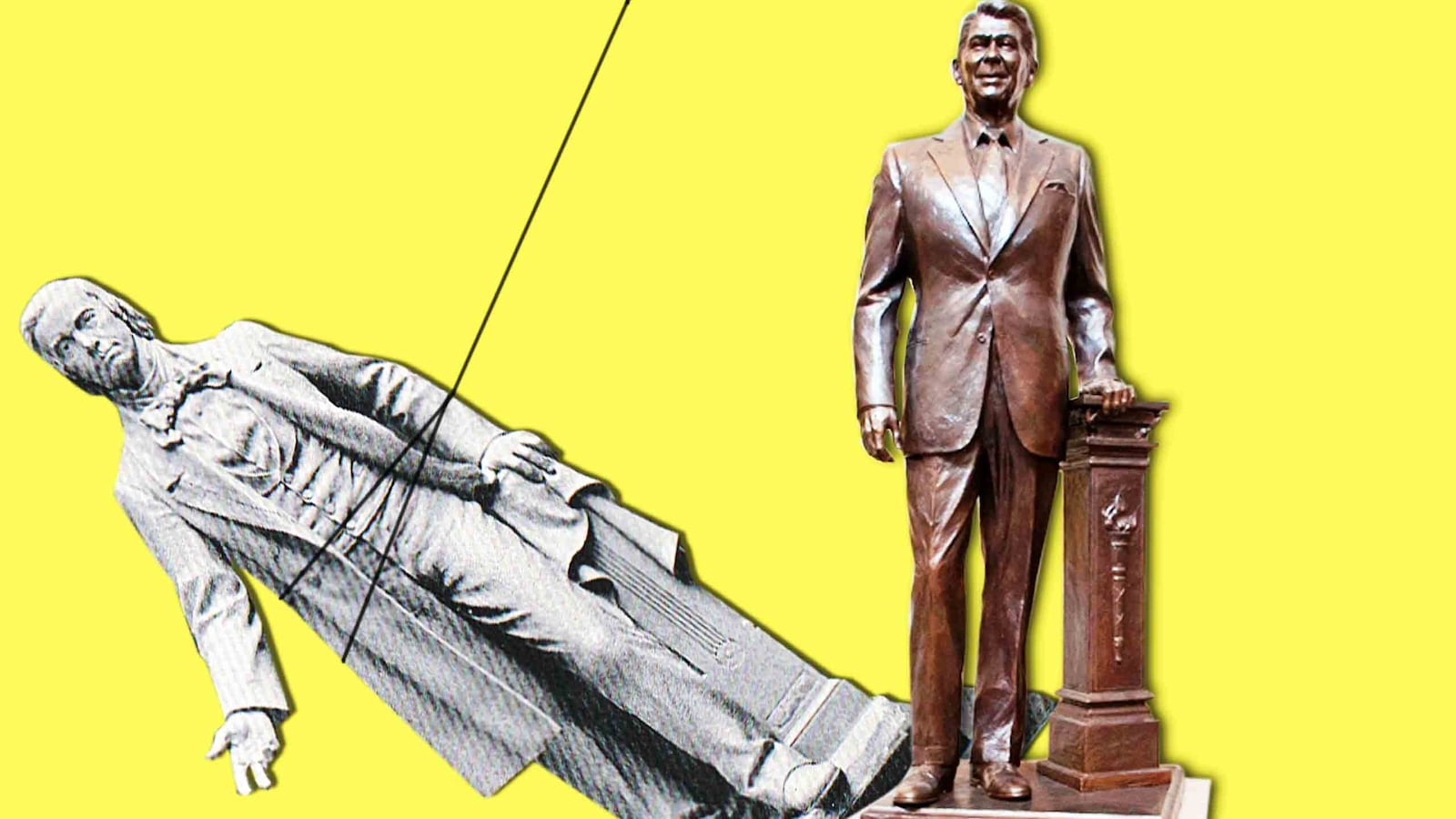

Amid America’s ugly brawl over slavery, King never let his patriotism turn harsh, defensive, pinched, or xenophobic. His patriotism was lyrical, expansive, idealistic, charitable and redemptive. Just 10 years ago, Ronald Reagan’s statue replaced King’s in the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. In this age of Monumental musical chairs, let’s move the marbleized figure of this big-hearted patriot into Donald Trump’s Oval Office—immediately.

Surprisingly, this California icon only lived out West for four years. King was as Bostonian as Clam Chowda. Born in 1824, King had to work as a clerk in his teens to support five younger siblings, when their father, a leading Unitarian Minister, died. This made him, he would say, “A graduate of the Charlestown Navy Yard.”

This humble-bragger emphasized that he taught himself French, Spanish, Italian, Greek, and German. But the description also represented the intellectual’s eternal insecurity, ever-aware that others are better credentialed, better known. At one point, a New York parish offered him a job, contingent on attending Harvard for a year. Insulted, King refused.

Still, King’s rise was extraordinary. By 1848, he had filled his father’s prestigious post at the Hollis Street Church. By 1850, Harvard granted the silver-tongued 26-year-old an honorary doctorate. And in 1852, he preached a sermon, “The Privileges and Duties of Patriotism,” that every American, nay every liberal nationalist, should master.

Today, we perceive the universalist critique of nationalism as “postmodern.” But as a serious Christian in an increasingly nationalistic world, King confronted that question too.

Some doubt “patriotism as a virtue,” King acknowledged, preferring “the law of love, unrestricted love.” These “cosmopolitan[s]” claim patriotism “interferes with the wider spirit of humanity,” calling it “sectionalism of the heart.”

Decades before the 20th century’s totalitarians loved humanity but hated—and murdered—humans, King countered: “You cannot love the whole world and nobody in particular.” He explained “However deep his baptism in general good-will, a man must look with a thrill that nothing else can awaken into the face of the mother that bore him; he cannot cast off the ties that bind him to filial responsibilities and a brother’s devotion.” Common ties foster community. A “common history, the same scenery, literature, laws, and aims” spawn “the wider family feeling, the distinctive virtue, patriotism.”

King defined patriotism as “love of country,” contradicting frigid “self-love.” Rejecting bunker patriots whose aggressive Americanism is un-American, he explained: “As the heart is kindled and ennobled it pours out feeling and interest, first upon family and kindred, then upon country, then upon humanity. The home, the flag, the cross, these are the representatives or symbols of the noblest and most sacred affections or treasures of feeling in human nature.”

King’s magnanimous patriotism recognized people’s instinctive tribalism as transcendent. By loving intensely, with loyalty, sentimentality, community, familial bonds can blossom into altruistic actions. But if you fail love and loyalty 101—you’ll never advance to the graduate level and save the world. Southerners’ “I’ll live and die in Dixie” nationalism soured; Northerners’ “Glory, glory, Hallelujah” nationalism soared.

Back in Boston, as his reputation grew, offers to move poured in. King feared he was being cowardly “in huddling so closely around the cosy stove of civilization in this blessed Boston.” In 1860 he decided “to go out into the cold and see if I am good for anything.”

Going West, the young man became a sensation. He helped San Francisco’s First Unitarian Church eliminate a $20,000 debt, then expand. He became the voice of union, championing democratic idealism in deeply divided California, a state which Abraham Lincoln won by only 711 votes.

Advocating “Liberty and Union,” this preacher was too patriotic to be apolitical. Pronouncing the rebels evil as not just disloyal, he proclaimed: “Rebellion sins against the Mississippi, it sins against the coast line; it sins against public and beneficent peace; and it sins, worse than all, against the corner-stone of American progress and history and hope—the worth of the laborer, the rights of man. It strikes for barbarism against civilization.”

King detested the South’s “traitorous aristocracy.” He backed the North’s “war of mass against class, of America against feudalism, of the schoolmaster against the slavemaster, of workmen against the barons, of the ballot-box against the Barracoon [slave barracks].”

King was working harder and harder, feeling worse and worse. When the war began, he shrewdly tied Californians to their fellow Americans through charity, raising $1.5 million for the Red Cross’ precursor, the American Sanitary Commission. Thanks to him, small, marginal California contributed one quarter of the national budget.

But he just couldn’t shake a sore throat—and bouts of “numbness in the brain.” In March, 1864, diphtheria combined with pneumonia killed him. He was only 39.

“Keep my memory green” he urged his wife. The San Francisco Evening Bulletin reported that this relative newcomer’s death “shocks” the “community… like the loss of a great battle or tidings of a sudden and undreamed-of public calamity. Certainly no other man on the Pacific Coast would be missed so much. San Francisco has lost one of her chief attractions; the State, its noblest orator; the country one of her ablest defenders.”

For decades, his memory glowed. An unprecedented 20,000 people attended his funeral. In 1929, California legislators designated him one of the top two Californians to memorialize in Washington. By the 1940s, his sarcophagus was one of the few not removed by San Francisco’s ban on burials.

Alas—Robert E. Lee fans take note—history progresses, standards change, monuments move. In 2007, the California legislature voted to replace King’s statue with Ronald Reagan’s. Most Californians had forgotten King.

It’s unfortunate. We need his message today. A patriot is much more than a missile. King understood that America spreads freedom globally: “The striking off of each new fetter here resounds cheeringly through Europe. A musical tone travels much farther than a growl; and the effluence of a righteous victory of freedom on our shores will reach farther at last… than the sputter of our musketry.”

“True patriotism,” King preached, “does not accept and glory in its country merely for what it is at present, and has been in the past, but for what it may be. We are living for the future. It doth not yet appear what we shall be.” That delicious mystery inspired King to work himself to death trying to make America truly grand. In determining “what we shall be,” let’s sing as lyrical and ethical a national song as Thomas Starr King did.

For Further Reading:

Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1973)

Charles W. Wendte, Thomas Starr King: Patriot and Preacher (1921)