The now-infamous white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, this past weekend was intended to spotlight and stop the removal of a Confederate statue in that city. The end result has been the hastening of the destruction of similar monuments nationwide.

For years, mostly Democratic lawmakers have warned that monuments meant to memorialize Civil War generals from the South could be catalysts for racist behavior and were best put in museums where historical context can be attached appropriately. On occasion, they’ve been successful in getting those monuments moved or removed. But the work has been painstaking. There are some 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy that can still be found in public spaces throughout the United States.

In the aftermath of a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, where 20-year-old James Alex Fields Jr. ran over and killed 32-year-old Heather Heyer, those efforts to remove those monuments have been emboldened.

In the immediate wake of the rally centered around a Robert E. Lee statue in the Virginia college town, a confederate statue was removed from downtown Gainesville, Florida, protesters toppled another in Durham, North Carolina, Baltimore city officials took down four monuments in the early hours of Wednesday morning, and a Robert E. Lee memorial, in Brooklyn of all places, is now going to be taken down.

Even in the former capital of the Confederacy itself, Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney announced on Wednesday night that his Monument Avenue Commission would include discussion of potential removal of monuments.

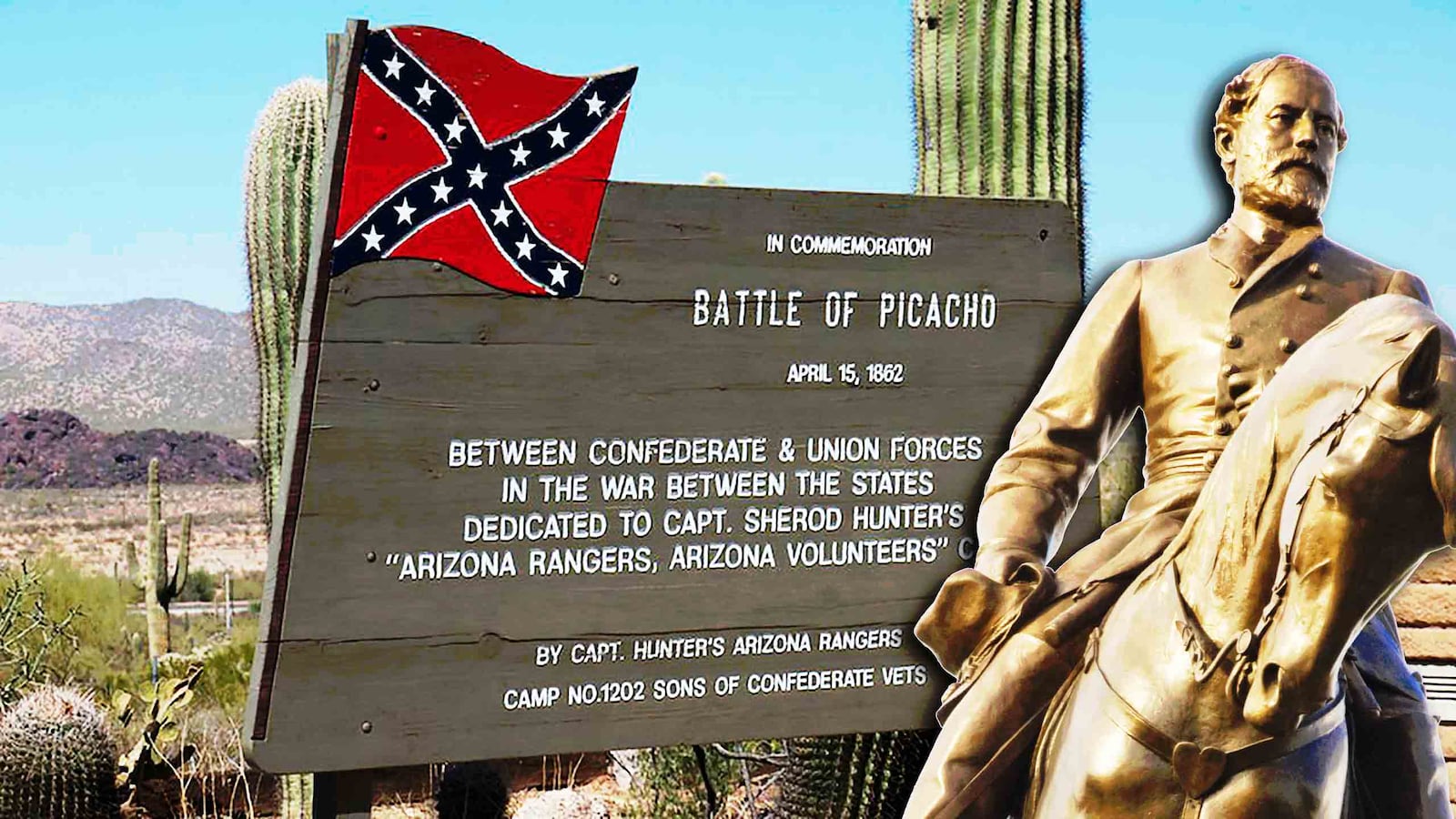

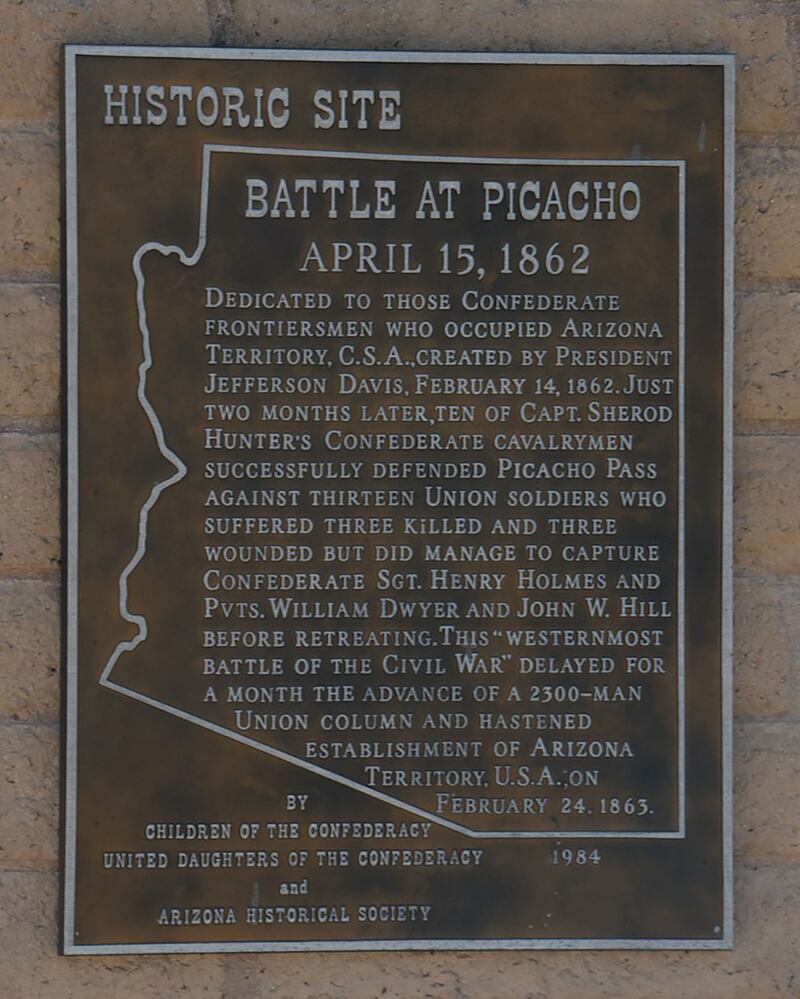

The movement to take down or move these monuments has gained steam that even the most optimistic advocates could not have anticipated. It’s also placed a spotlight on just how far and wide these memorials reach. Symbols of the Confederacy can be found in states like Montana and Arizona that clearly had no historical ties to the lost cause, an oddity that has struck some lawmakers in those states as terribly insensitive.

“Imagine if you were an individual, a descendant of individuals that were slaves,” Arizona state Rep. Reginald Bolding told The Daily Beast. “Your ancestors were raped, murdered, and hung and then be asked in the same breath to use your taxpayer dollars to honor those same individuals.”

There was no state of Arizona during the Civil War. There was a territory, which was claimed by Confederate states following the 1861 Battle of Mesilla, fought in present-day New Mexico. The Confederate control of the area was later ceded and the territory was relocated to Texas. And Arizona eventually became a state in 1912.

It would be 40 years later that the state erected the first of six Confederate memorials. The latest was put up in 2010. Starting in 2015, Bolding began calling for the removal of Arizona’s confederate memorials following the murder of nine members of a black church in Charleston by Dylann Roof, a white supremacist who embraced Confederate iconography. But his calls went unheeded.

That may very well happen again after Charlottesville. To date, Arizona’s Republican governor, Doug Ducey, has condemned the racist groups at the rally but said “it’s not my desire or mission to tear down any monuments or memorials.”

But even those defending the idea of keeping the monuments in place seem wary of the changing political dynamics. The Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy were largely responsible for putting Arizona’s Confederate memorials in place. A local chapter did not immediately respond to a request for comment from The Daily Beast. But the national organizations, which are interested in preserving the statues nationwide, seemed aware that their cause had been harmed by the protesters who had descended on Charlottesville.

A statement from the Sons of Confederate Veterans, provided to The Daily Beast, denounced the “radical leftists” who were leveling hatred “against our glorious ancestors.” But it also warned that the white supremacists had “tarnish[ed] the good and glorious name of the Confederate soldier.”

A Taste For Different Tactics

In an effort to remove or relocate Confederate plaques and statues, lawmakers have tried an array of strategies, some not always political. In San Antonio, Councilman Roberto Trevino has said that the statue in the city’s Travis Park has been misidentified as being Colonel William Travis, an American who died in the Battle of the Alamo and the park’s namesake.

“There’s that misconception and for those that are arguing about protecting history, that’s one important element of our effort,” Trevino told The Daily Beast. “We’re trying to create less ambiguity between the monument and the park itself.”

In other cases, the fight has been waged in the courts, pitting cities against state commissions who are in charge of what are deemed to be historical landmarks. The city of Memphis has been mounting a legal effort to convince a state agency to remove a statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest from a park in the city for years. In 2015, the Memphis city council voted in favor of removing the statue only to have the request denied by the Tennessee Historical Commission (THC), who had jurisdiction over the structure.

After Charlottesville, the city is taking another stab at it.

“As I’ve said before, [the statue] doesn’t represent the values of the people of Memphis,” the city’s Chief Legal Officer Bruce McMullen told The Daily Beast. “We’re about inclusion and working together.”

In October, the THC board is set to meet, during which time the city plans to present an appeal over the commission’s initial decision. Should the appeal not be granted, McMullen said the city is prepared to take its legal battle all the way to the Supreme Court of the state.

For Democrats who are not currently in power, but in the midst of various campaigns for statewide office around the country, the call for Confederate statue removal has been galvanizing. Stacey Abrams, a Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Georgia, assailed her state’s Stone Mountain monument that depicts three Confederates on horseback with their hats over their hearts. She wants it gone as quickly as possible.

“Those three men are riding triumphantly in celebration of their terrorism against African Americans,” Abrams bluntly told The Daily Beast. “We don’t need to celebrate it. It certainly should not be given the prominence it’s given on Stone Mountain.”

It’s a cause that Georgia Democrats have championed in the past, though often with wariness that it might not resonate statewide. Abrams still isn’t confident that the current state government would act on this request. But the compulsion to make it has become morally and politically more profound.

“I think every tragedy reminds us of the work we have to do to improve and perfect our nation,” Abrams said. “In the wake of the white supremacist attack and murder in Charlottesville, we have a renewed call.”

As for what could go in the monument’s place, the metro Atlanta chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America suggested the rap duo OutKast.