“What does America stand for?” is a question with many answers to many people around the world, even more than “What should America stand for?” The crisis today isn’t which answer is the best, or even which question is most relevant, but the fact that neither question is being asked much at all in America itself even during this heated presidential primary election season.

2016 isn’t simply a choice between pushing the swinging pendulum of American politics back again or continuing with the status quo. Nor is it a choice between extremists and centrists (or “primary extremists” who will magically transform into centrists even before the last convention balloon has popped). Both the Republicans and the Democrats have had their dalliances with relatively extreme ideological nominees in the past. They have not fared well in the general election. Barry Goldwater may have laid the ground for the Reagan Revolution in 1964, but he was battered by Lyndon Johnson. George McGovern might not have looked so bad in hindsight after Richard Nixon met his Watergate, but that doesn’t change the fact that he made Nixon look like Napoleon in the 1972 landslide.

Next year’s election could look similar if Donald Trump or Ted Cruz come out of the GOP primary to gift-wrap the election for Hillary Clinton. The Tea Party remnants, evangelicals, and other groups who appear to hold so much sway in the Republican primary are not a big enough base for a candidate who has offended nearly every other group in America.

ADVERTISEMENT

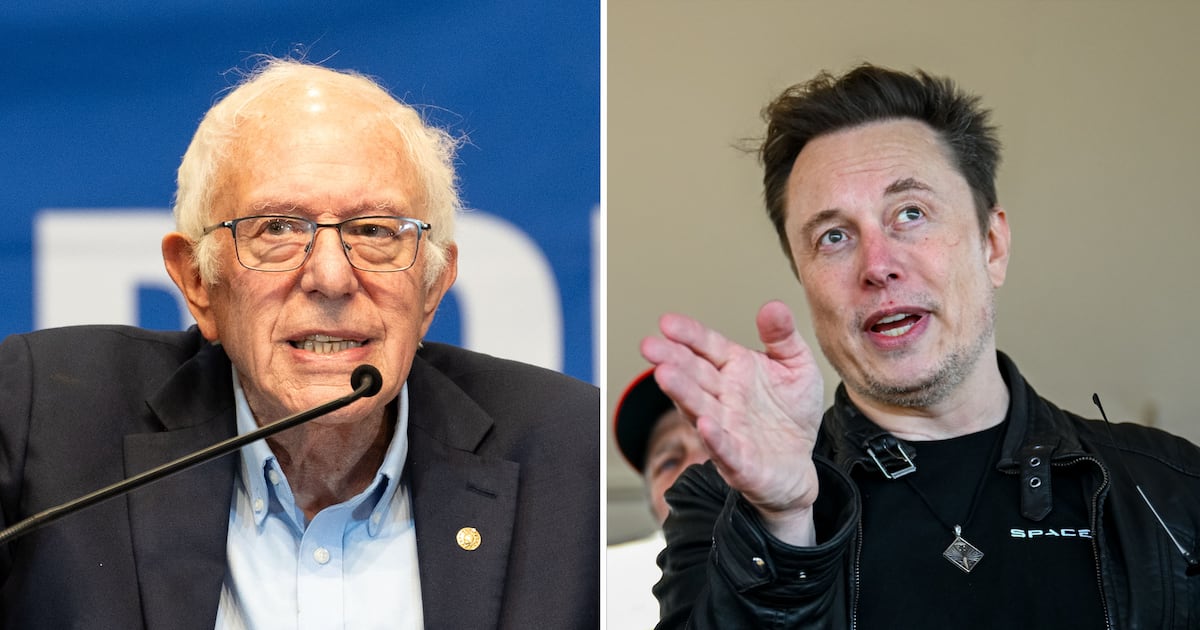

Or 2016 could enter uncharted territory if Bernie Sanders sticks around long enough to pull Hillary even further to the left. She’s no ideologue, but the more the Democrats follow Sanders down the Socialist path the more we have to wonder what it will be like to have a Goldwater versus a McGovern election with no sane center in sight. What happens when the GOP is Nationalist, the Dems are Socialist, and Trump is National Socialist? I’m sure I’m not alone in not wanting to find out.

This risk is even greater in foreign policy. Clinton has essentially endorsed President Obama’s play-acting policy, as befits his former Secretary of State. The Obama White House sees the Islamic State as a communications problem that would go away if only the American people would agree that the White House is doing a great job—despite 75% of Americans saying the battle against terror is not going well. Meanwhile, Obama and John Kerry continue to insist that Vladimir Putin can be an ally, an idea that was naïve seven years ago, foolish four years ago, and can’t be called anything less than insane or suicidal at this point. With security now the top issue for most Americans, it’s awkward for Hillary to denounce the do-nothing Obama policy that has led this to be the case since she was one of its architects.

Coming to rescue Clinton from this dilemma is a new breed of GOP neo-America First nationalist/isolationists whose tenets seem to be that 1) America is God’s chosen nation and 2) the rest of the world can go to Hell. This is dubious theology at best, and the fact that America won’t be in good shape for long if the rest of the world is in flames should be obvious. The Cruz-Trump line that the United States can prosper while hiding between two oceans and occasionally carpet-bombing a far-off land is preposterous as well as morally repugnant.

The America Firsters who wanted to keep America out of World War II had a first principle that said, “No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America.” That was quickly refuted by Pearl Harbor (immediately after which the America First Committee disbanded) and has been disproved even more emphatically by the 9/11 attacks and the spate of foreign and homegrown terror attacks in recent months. Playing defense hasn’t worked since 1941 and, thanks largely to technology, attacks are only getting easier.

The isolationists also ignore the fact that globalized economies have global interests and that stability is essential for global trade. Unless the U.S. is prepared to roll back the countless benefits its companies and citizens reap from cheap energy and global markets for American products and services, walking away as the chaos grows is self-destructive in the extreme.

To be fair, Donald Trump isn’t exactly isolationist in the way Cruz and Rand Paul are. If it’s possible to glean anything from Trump’s incoherent statements on foreign affairs, it’s that he favors bombing terrorists while partnering with those who sponsor and protect those same terrorists. If this sounds like just another outrageous Trump position, this is the policy of the supposedly supremely rational Barack Obama, who has made deals with Cuba and Iran, held peace talks with Putin, and walked away from his Syrian red line, which has since been painted many times over in blood by Bashar Assad.

Obama’s sporadic military interventions with no long-term strategic basis are intended to improve poll numbers, not national security. Saying the U.S. cares, but only enough to drop a few billion dollars’ worth of explosives—often hitting civilians and infrastructure—makes things worse. Telling the world to go to Hell is bad enough; doing so while fanning the flames even hotter is sickening. A foreign policy choice between more Clinton/Obama lip service and Trump/Cruz nationalism is terrifying.

After two two-term presidents with diametrically opposed ideologies on foreign policy and domestic affairs, America is facing an existential challenge. Is it to be just another country, one more nation-state that just happens to be much richer and stronger than any other? Or is there still a case and a cause for American exceptionalism that says that the only nation founded on the idea of freedom has the obligation to use its immense wealth and power to promote that freedom elsewhere?

My personal answer isn’t much of a surprise since it’s one that I share with nearly everyone who has lived in an unfree state or who has had their freedom mortally threatened. I grew up in the Soviet Union in a mixed family—and I don’t mean my Armenian-Jewish heritage. My Baku relatives included die-hard Communists who would excuse nearly every catastrophe and shortage as the fault of flawed individuals, not the state or the system. They lived in a fragile truce with my father and his brother and cousins, natural skeptics who wanted me to grow up without illusions.

For an inquisitive child who was included early on in family arguments, there were clear flaws in the delightful theory that everything should be shared “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” I had been exposed to a real meritocracy early in life at the chessboard, and the idea that it was wrong to enjoy the fruits of success seemed ridiculous. Why work hard if my hard work produced no benefits for me and my family? And if Socialism was so wonderful, why did it have to be imposed by force? Why could the great and generous state only be criticized in whispers?

Of course the Soviet authorities were well aware of these contradictions and their subversive effects, and so they subverted their own propaganda with hypocrisy. There were rewards for success, to a degree, establishing the principle of “everyone is equal, but some are more equal than others” so well summarized in George Orwell’s Animal Farm. It turned out that not even the chessboard was safe from politics, as I discovered when I began my assault on chess Olympus and the reigning world champion, establishment darling Anatoly Karpov.

Thanks to chess, I also had the rare privilege of foreign travel as a teenager, which gave me the chance to witness the horrors of capitalism and democracy with my own eyes: high living standards, functioning institutions, a vibrant civil society. It didn’t take long for me to realize that the West was the real world and it was my home that was the charade. I began to speak publicly about this disconnect in interviews with Western publications, pushing my luck as a celebrity and also pushing the edge of creeping liberalization under Mikhail Gorbachev. Chess had long been an ideological tool to promote the superiority of the Soviet Man over the selfish and lazy West. So it was quite a scandal for the Soviet world champion to proclaim his admiration for Americans as “close to true human nature,” as I did in the summer of 1989—to Playboy magazine, no less.

When Ronald Reagan went to Berlin and demanded that Gorbachev “tear down this wall” in 1987, it was difficult for most of us living behind that wall to imagine its fall could be anything but a blessing for us. It was not mere rhetoric; it was a tangible demonstration that people on the outside cared about our fate, and were fighting to free us from it. Having been raised to think of the United States as an enemy that might bomb us into oblivion at any moment, this evolution to thinking of the U.S. as an ally—of the Soviet people, against our leaders—was no small transition. How are the oppressed people of Russia, Iran, and Syria supposed to feel about America today when they see Obama making deals that empower their despotic rulers?

The end of the Cold War also marked a transition of how Americans were perceived in the world and how they perceived themselves. It’s one thing to be the good guy in the movie when there is an Evil Empire to vanquish. With no rival worth the effort after the USSR’s collapse, the white cowboy hat of Ronald Reagan was retired. It made a brief reappearance on the uneasy head of George W. Bush after 9/11, but the catastrophic outcome of his invasion of Iraq put it back in the closet. Regardless of where you stand on the 2003 Iraq War, and because of my background I cannot condemn any action that removes a dictator, that it took so much campaigning and falsified evidence to generate public support was a clear sign that Americans had moved on from the business of fighting evil. But the Iraq War was a rebuke to bad planning and lousy implementation, not a refutation of the idea that America can be an essential force for good in the world. America must do better, not do nothing.

No matter how much the isolationists and pacifists want to believe it, the jihadists, dictators, and other threats to American lives and its interests will not disappear even if the U.S. continues to retreat from every global challenge and conflict. Nor will ceding geopolitical influence and security commitments to other nations make the world safer or more stable, especially if that power is ceded to aggressive dictatorships like Iran and Putin’s Russia.

Europe is closer to the front lines against jihadism and Putin’s aggression but has let its military atrophy along with its will to use it. The complete lack of a coherent EU security policy means that unless the United States rediscovers its role as an active force for stability and security in the world, both stability and security are in trouble. If stopping the Islamic State is a real priority—as Obama says it is, as every 2016 candidate says it is, as the American people say it is—then it should not be so difficult to discard the policies that have clearly failed to do so.

Seventy years ago, Harry Truman built new institutions and made a huge investment in stabilizing Europe and stopping the advance of Communism world-wide. The CIA, NSC, NATO, Voice of America, and the Marshall Plan, intervention in Greece, Taiwan and Korea, all parts an ambitious economic, military, and communications offensive to fight and win the Cold War. The GOP fought Truman on many of these bold plans, as did members of his own cabinet, but eventually the containment model was accepted by the Republican Eisenhower and every subsequent administration as a necessity.

So far Marco Rubio is the only prominent candidate to demonstrate the preparation and instincts to return America to its vital role, but even he has been limited by poll numbers and intimidated by the focus groups that insist America should mind its own business until it goes out of business. I hope that there is still a place in 2016 for an optimistic vision that calls for using America’s incredible resources to help instead of harm, to build instead of bomb, to free the oppressed instead of bargaining with their oppressors, and to protect the innocent instead of considering them collateral damage.

Americans have become accustomed to demanding the impossible and their politicians have become accustomed to providing it. Massive debt fuels education and the stock market. Calls for greater security are accompanied by a refusal to invest or sacrifice to achieve it. The bipartisan acceptance of reality has gone missing in America’s hyper-partisan political environment. The idea that America must be a force for stability and freedom has been abandoned by Washington, reflecting an American Main Street more interested in fleeting stock market values than in the lasting values of global democracy. 2015 was a dangerous year and 2016 will be even more dangerous unless America remembers what it stands for.