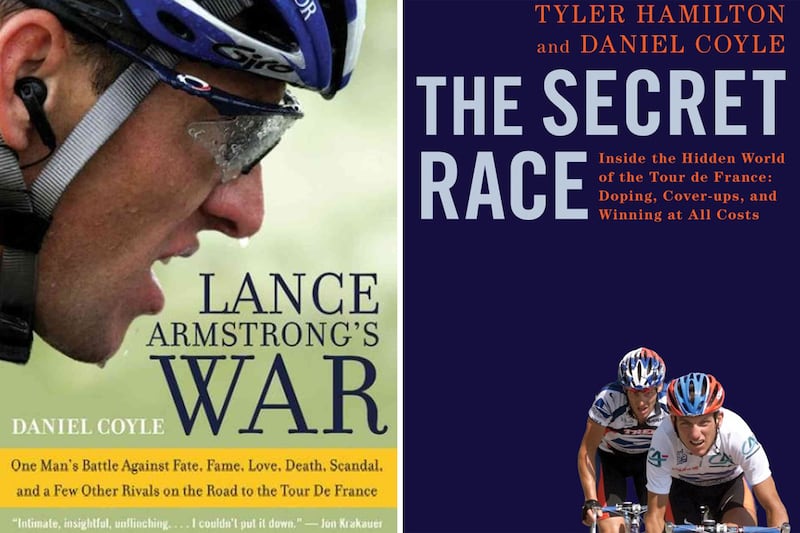

In 2005’s bestselling Lance Armstrong’s War, author Daniel Coyle was able to gain somewhat intimate access to Armstrong and his team during the 2004 Tour de France. The book touched on doping allegations but was not critical of the cyclist. Then Coyle gained wide access to the cycling world when he wrote 2012’s The Secret Race with Armstrong teammate Tyler Hamilton. The accusations and evidence against Armstrong flowed. Here are the biggest revelations.

From Lance Armstrong’s War

Dr. Evil

Coyle closely observed Michele Ferrari, the infamous Italian sports doctor who was dubbed “Dr. Evil.” Coyle was able to talk to Ferrari in part because the writer agreed he wouldn’t ask about doping. Ferrari was Armstrong’s trainer until he was found guilty of sporting fraud and abusive exercise in October 2004, though he was acquitted in 2006. But Ferrari is famed in the cycling world for his alleged ability to hide doping, and Coyle writes that Ferrari worked far more closely with Armstrong than previously thought. Last June, the USADA charged the doctor with administering and trafficking prohibited substances; he decided not to contest the charge and was issued a lifetime ban from the sport.

Doping’s History

Philippe Gaumont of the French Cofidis team once admitted to blood doping, which involves blood transfusion to boost red blood cells, and said he would rub salt on his testicles until they bled so he could get a doctor to issue him banned cortisone. Ex-Kelme rider Jesus Manzano provided a list of 29 drugs he said his team told him to take. He nearly died during the 2003 Tour de France when he was accidentally given someone else’s blood. Doping wasn’t illegal in the early days of cycling, and Jacques Anquetil, who won the Tour five times, said, “Only an idiot thinks that a professional cyclist who rides 235 days a year can hold himself together without stimulants.” In the 13 months leading up to the 2004 season, seven riders died of heart attacks. It’s often repeated that Armstrong could not have been the only one clean in such an atmosphere.

Floyd Landis

Landis, who was primed to succeed Armstrong, worked closely with Ferrari and Armstrong during the 2004 tour. In one colorful exchange, Landis and Ferrari joked about doping. “Naps are illegal, right, Michele?” Landis said. “Spaghetti too, of course,” Ferrari said. Landis and Armstrong became close friends, as the two had a similar ultracompetitive personality. But there was also tension. “I would love to know what’s going on inside his head,” Landis told Coyle of Armstrong. “Lance doesn’t want a hug. He just wants to kick everyone’s ass.” Landis would go on to be stripped of his 2006 Tour win after testing positive for drugs. In 2010, he admitted to doping and accused Armstrong of the same, which helped the USADA’s case against Armstrong.

L.A. Confidentiel

David Walsh, who covered cycling for many years and admired Armstrong in the beginning, questioned him in 2001 about why the cleanest cyclist in the world was working so closely with Ferrari. When Armstrong found out Walsh was writing about him for a Sunday Times article, Walsh said, Armstrong tried to undermine their story by leaking it to a newspaper. In 2004, Walsh and French journalist Pierre Ballester released L.A. Confidentiel: Les Secrets de Lance Armstrong. In it, Walsh interviewed Emma O’Reilly, Armstrong’s personal masseuse, who said she would lend Armstrong makeup to cover up needle bruises on his arm. Some of the allegations were referenced by The Sunday Times, and Armstrong immediately filed suit against the paper, and against Walsh and O’Reilly as well. The emotional toll on O’Reilly would become severe. In 2006, The Sunday Times settled with Armstrong and issued an apologetic statement. In 2012, the paper said it would attempt to recover the money lost in the settlement.

Masked Guilt

Coyle reiterates many of the accusations against Armstrong, which, he says, were nothing new to the rider. But he notes that Armstrong had been “treated with unparalleled levels of suspicion” even though he “came up clean each time” despite having been tested 30 to 40 times a year. He noted that Armstrong cooperated with the French authorities and the USADA, and even donated money to testing programs. Many have pointed out since that such tactics were designed to mask his guilt.

From The Secret Race

‘Admission’

Coyle’s book with Tyler Hamilton, Armstrong’s longtime teammate, starts much earlier, encompassing Armstrong and Hamilton’s entire careers. One day in the fall of 1996, when Armstrong was still recovering from cancer, his friend and teammate Frankie Andreu and his wife, Betsy, visited him in hospital. Two doctors entered the room and asked Armstrong if he’d ever used performance-enhancing drugs. Hamilton writes that, in front of the Andreus, Armstrong said yes, matter-of-factly. “He’d used EPO, cortisone, testosterone, human-growth hormone, and steroids ... This is a classic Lance moment, being cavalier about doping ... He wants to minimize doping, show it’s no big deal, show that he’s bigger than any syringe or pill.” Betsy Andreu has talked about this encounter many times, including testifying under oath. Armstrong also denied it under oath and has attacked Andreu repeatedly.

EPO in the Fridge

In the spring of 1999, Armstrong assembled his inner circle at his French villa in Nice to map out the plan for the Tour. When Hamilton arrived, he and Coyle write, he badly needed some EPO, and he asked Armstrong for some. “Lance pointed casually to the fridge. I opened it and there, on the door, next to a carton of milk, was a carton of EPO ... I was surprised that Lance would be so cavalier.”

Motoman

For the 1999 Tour, Hamilton says Armstrong sketched out the plan: he would pay his gardener and handyman Philippe, a.k.a. Motoman, to follow the Tour on his motorcycle, carrying a thermos full of EPO for Armstrong, Hamilton, and a third teammate, Kevin Livingston. The riders would call him on a secret prepaid cellphone, and he would make a drop-off. They dropped used syringes in an empty soda can: the Radioactive Coke Can. Armstrong won the “Tour de Fucking France,” a feat hailed as a miracle for the cancer survivor. President Clinton phoned him. But he had tested positive for cortisone after the prologue stage. Hamilton writes that U.S. Postal made up a cover story and said Armstrong had a saddle sore, backdating a prescription for a cortisone skin cream. UCI was not serious about testing or getting Armstrong, so the issue went away. When they had extra EPO, Armstrong suggested giving it to other teammates who were not in on the Motoman drop.

Blood Bags

Just before the 2000 Tour, team director Johan Bruyneel flew Armstrong, Hamilton, and Livingston to Spain to have their blood drawn by Spanish doctor Luis Garcia del Moral and his assistant, Pepe Marti, Coyle and Hamilton write. “It would be like taking EPO, except better ... You’re watching a big clear plastic bag slowly fill up with your warm dark red blood. You never forget it.” This blood transfusion was called BBs, or blood bags, and had to be done in the days leading up to the race, as red blood cells can only live for about 28 days, and giving blood is also very draining. Before the crucial stage 12 on Mont Ventoux, where Armstrong’s nemesis Marco Pantani would attack, the riders entered their hotel room to find their blood bags taped to a wall above their beds, ready for transfusion. Two days later, Armstrong blew by Pantani on the summit.

Microdosing

To prepare for the 2001 Tour, Armstrong rode in the Tour of Switzerland. Ferrari advised Armstrong to sleep in an altitude tent and to drip EPO into his vein all night, according to the book, so it would go straight into the bloodstream and then go away. “In this, as in other things, Lance was blessed: he had veins like water mains.” Hamilton says it took the authorities years and millions of dollars to develop a test for EPO, and “it took Ferrari five minutes to figure out how to evade it ... The tests are easy to beat. We’re way, way ahead of the tests. They’ve got their doctors and we’ve got ours, and ours are better. Better paid, for sure.” But Armstrong tested positive for EPO during that Tour of Switzerland. “I know because he told me,” Hamilton writes. “No worries, dude,” he says Armstrong told him. “We’re gonna have a meeting with them. It’s all taken care of.” According to sources within the FBI, a UCI official had intervened in the test and stopped it. Armstrong later made two donations totaling $125,000 to the UCI.

60 Minutes

In March 2011, 60 Minutes contacted Hamilton and asked for an interview; he agreed. He repeated many of his confessions and accusations against Armstrong. The segment aired in May. In June, the owner of Armstrong’s favorite restaurant in Aspen, his new home, called him to tell him that Hamilton was having dinner there; Armstrong rushed over. Hamilton says Armstrong told him: “I’m going to make your life a living ... fucking ... hell.”