In his introductory note to James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, historian C. Vann Woodward noted that the book, which was part of a 10-volume series on American history, was the only entry in the series to be devoted to a single war. Was the Civil War that important? Certainly the subject is insanely popular with amateur history buffs and even quite a few professional historians. Still, a whole book about one war? Woodward, the editor of the series and himself one of the great authorities on Southern history, defended the decision this way: “There are numerous criteria at hand for rating the comparative magnitude of wars … One simple and eloquent measurement is the numbers of casualties sustained. After describing the scene at nightfall on September 17, 1862, following the battle called Antietam in the North and Sharpsburg in the South, McPherson writes: ‘The casualties at Antietam numbered four times the total suffered by American soldiers at the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. More than twice as many Americans lost their lives in one day at Sharpsburg as fell in combat in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War combined.’ And in the final reckoning, American lives lost in the Civil War exceed the total of those lost in all the other wars the country has fought added together, world wars included. Questions raised about the proportion of space devoted to military events of this period might be considered in the light of these facts.”

Gallery: The Photos of the Civil War

Is there an inch of battleground, a day or a minute between 1861 and 1865 left unexamined by some historian somewhere? Surely not. But the library of books about the Civil War that now exists—and is sure to swell during the war’s sesquicentennial which begins this week—is absolutely worth it. The Civil War was not just the bloodiest American conflict. It was also the war that settled who we are as a nation, a war whose outcome and rhetoric have defined us ever after.

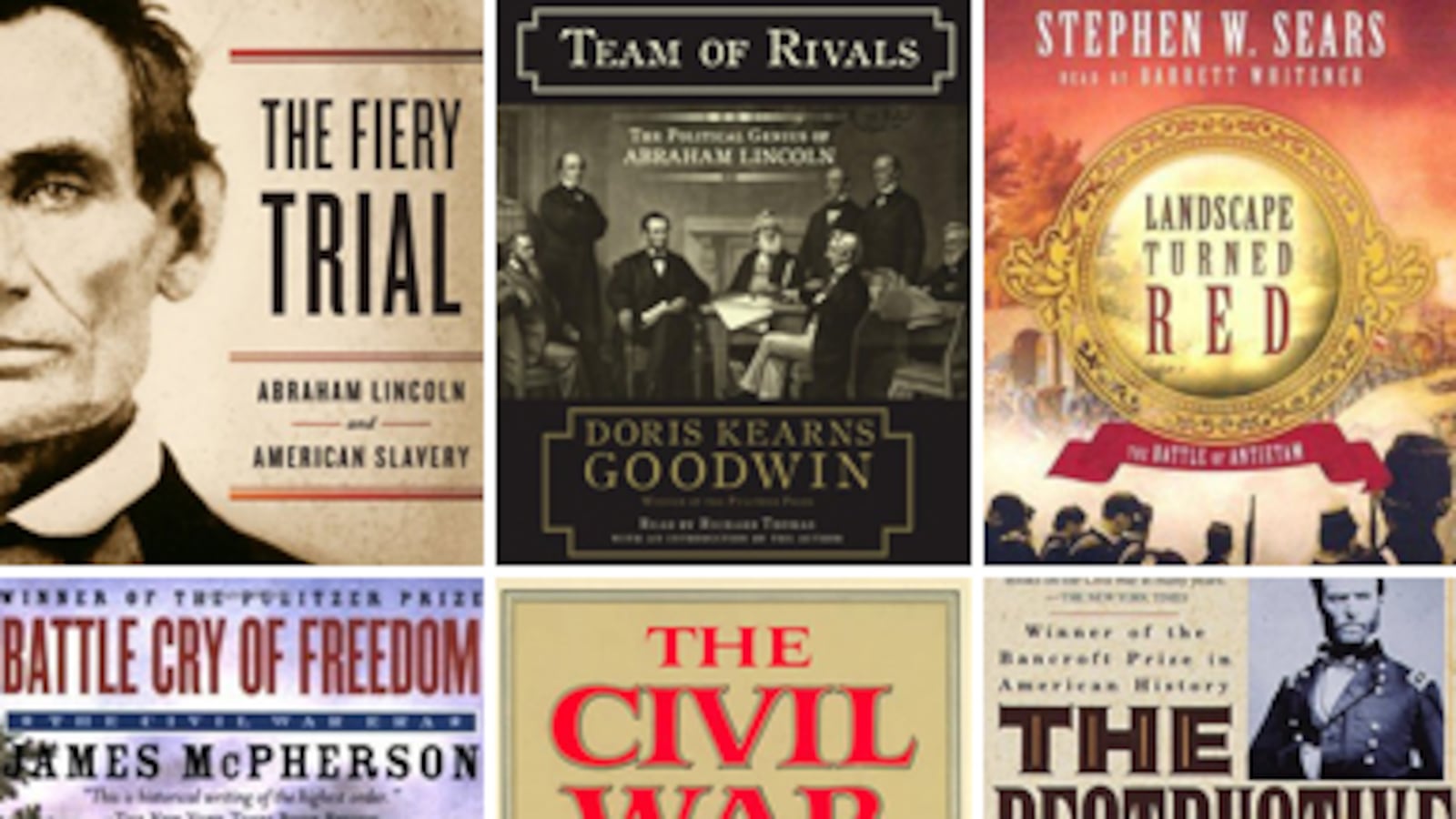

Compiling a list of essential books about the war is an absurd task, simply because—no kidding—so many are essential. Try to imagine another subject where you omit writers of the caliber of William McFeely, Bruce Catton, T. Harry Williams, or Burke Davis. So consider this list a mere starting point. The more you read about the war, the more you will want to read (don’t say you weren’t warned). And when you tire of history, there’s Civil War fiction. But that’s a subject for another list. So this list is missing some great ingredients. Still, you have to start somewhere.

Battle Cry of Freedom By James McPherson

The Confederates don’t open fire on Ft. Sumter until page 273, and if that doesn’t tell you that this historian is all about context, then nothing will. But if ever a conflict wanted context to be understood, this is the war. McPherson begins with a brief look at the Mexican war of 1847, where many of the men who would determine the course of the Civil War first saw combat or held commands. He then moves through Bloody Kansas, Dred Scott, and the various compromises that came and went as an ever more fractured nation sought ever more patchwork ways to hold together. The lesson is clear: battles are fine, but you have to understand the why—the arguments and assumptions and predispositions that led to the battles and in many cases affected their outcome. If any of this sounds dry, it isn’t. McPherson is a skillful writer and a discriminating historian. There are very good reasons why this book is so often called the best single-volume history of the war, and to find out why, all you have to do is open it and read a few pages. After that, it’s mighty hard to stop.

The Civil War: A Narrative By Shelby Foote

There are things wrong with this epic trilogy—Foote isn’t reliable on the causes of the war, for instance—but what’s right far outweighs the negatives. The author deeply understood the importance of the war in the West—meaning the lower Midwest and the South that abutted the Mississippi. For a Southerner, he is relatively immune to the cult of Bobby Lee. He understands the military mind and what it takes to be a soldier. And he brilliantly shows how Lincoln grew into his job, how he became the Lincoln we know. Most important, no one has ever written so well on this subject, and probably never will. A fine novelist before he tackled the Civil War, Foote displays the novelist’s eye for story and character—the Gettysburg section, in particular, reads like Greek tragedy, full of blood and hubris. Foote thought the Civil War was America’s Iliad, and he caught the epic quality of the conflict he chronicled.

Landscape Turned Red By Stephen Sears

As a battle, Antietam might be called a draw. The Union held the field at the end of the day, but the Confederate army slipped away without further repercussions. But Sept. 17, 1862 was a memorable day for several good reasons. First, it was the bloodiest single day of an astonishingly bloody war, with casualties (dead, wounded, or missing) for both sides totaling 22,720 men. Second, the Union’s vacillation after the battle gave Lincoln the excuse he needed to sack the irresolute George McClellan as the leader of the Army of the Potomac. Third, because the Union could claim the victory—and at this stage in the war, the North needed every victory it could find—the good news gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on Sept. 22. Books about single battles are usually fit only for obsessives, but this crucial moment deserves its own book, and Sears gives it a superlative rendering.

Memoirs By Ulysses S. Grant

After Lincoln and Jefferson, Grant, of all people, was probably the finest prose stylist ever to inhabit the White House. Some of what made Grant a great general made him a good writer as well, notably his ability to balance the big picture with dozens of details. His descriptions of battles proceed almost minute by minute in some cases, but he never becomes mired in minutiae, and the story proceeds with an almost martial tempo. If Grant lacks Lincoln’s rhetorical genius, he makes up for it as an always straightforward stylist who prizes clarity above all.

Daily life in the upper-middle class South during the war, as rendered by a supremely self-aware—and ultimately very likeable—lady. The Chesnut diary was one of the first non-military documents whose publication did much to increase interest in wartime life off the battlefield. Open to almost any page and you will see why. She didn’t miss much.

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War By Drew Gilpin Faust

The Civil War remade many attitudes but none so much as the thinking on death. Carnage and slaughter on a grand scale ground down prevailing notions of the good death and undercut belief in divine providence. Many new ways of thinking about death came out of the war, but none more sweeping than the new expectations of the military—its responsibility to identify, preserve, and honor the dead. This is one of those groundbreaking histories that clarifies a crucial piece of the past previously ignored.

The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans By Charles Royster

Both sides were guilty of screaming for blood, and both sides got what they asked for and a lot more. The Civil War was not the first total war, that is, a war carried past armed combatants to include civilians and private property. But modern technology—railroads, more sophisticated arms—made slaughter easier, and the vengefulness with which each side went at the other made the killing and burning and looting even more inevitable. The embodiments of this ruthlessness were William Tecumseh Sherman on the Union side and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson on the Confederacy. Their foes demonized them as zealots and fanatics, while their allies hailed them as, well, zealots and fanatics. Their excesses were deemed necessary to victory, but when the butcher’s bill came due at war’s end, four years of horror had numbed all but the most resolute warmongers.

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln By Doris Kearns Goodwin

Goodwin portrays Lincoln by portraying the men who competed with him for the presidency, men whom he thereafter drew into his cabinet (keep your enemies close, etc.) to help him prosecute the war. Each man saw Lincoln from a different perspective, but the sum of their perspectives gives a marvelously rounded look at a man who was as hard to define as anyone who has ever occupied the oval office.

The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery By Eric Foner

Our best historian on Reconstruction, Foner argues that "the hallmark of Lincoln's greatness was his capacity for growth." The 16th president did not come out of the cradle as the Great Emancipator. His philosophy matured as he aged, and, because he was a politician always acquainted with what was possible, as opposed to what was desirable or preferable, he trimmed his thinking depending on who he was dealing with and the circumstances surrounding those dealings. He was enigmatic, even to his friends, and he left a scant paper trail—Honest Abe was no confessional diarist. Nor was he always right or always wise. The Lincoln who emerges in these pages is always human and vitally engaged with his times but capable of error and mistakes in judgment. Watching him grapple with the single most important issue of his time, we realize that knowing him completely will always be impossible but that our admiration for him, the absolute right man at the right time, can only continue to grow.

Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory By David W. Blight

The Gilded Age author William Dean Howells once said, "What the American public always wants is a tragedy with a happy ending." As Blight demonstrates, when they didn't get what they wanted, they fiddled with the historical record until it came out the way they liked it. Or white people did, anyway. In the half century after the war, the country succumbed to a sort of cultural amnesia whereby a war over slavery became a war over states’ rights. Cause and effect were uncoupled, such that valor might exist in a vacuum—what the fight was about became less important than the way in which it was fought. African Americans had their own counternarrative, but no one else paid attention to theirs as everyone rushed to embrace reconciliation of the two halves of the country. In the white man’s playbook, healing trumped everything, with the result that the real lost cause was truth. The North may have won the war, but the South dictated the terms of the peace for almost a century.

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War By Tony Horwitz

This absurdly fascinating book begins with a look at reenactors, and then it gets really weird. Most of Horwitz’s subjects are Southerners whose lives are, in various ways, taken over by their interest in the war. The author quotes Shelby Foote for the epigraph: “Southerners are very strange about that war.” Some of the people in this book, such as the Scarlett O’Hara impersonator, may look silly, but make no mistake, they are all in the grip of an obsession, every bit as convinced as Faulkner that “the past isn’t dead, it’s not even past.”

Malcolm Jones writes about books, music, and photography for the Daily Beast and Newsweek, where he has written about subjects ranging from A. Lincoln to R. Crumb. He is the author of a memoir, Little Boy Blues, and collaborated with the songwriter and composer Van Dyke Parks and the illustrator Barry Moser on Jump!, a retelling of Brer Rabbit stories.