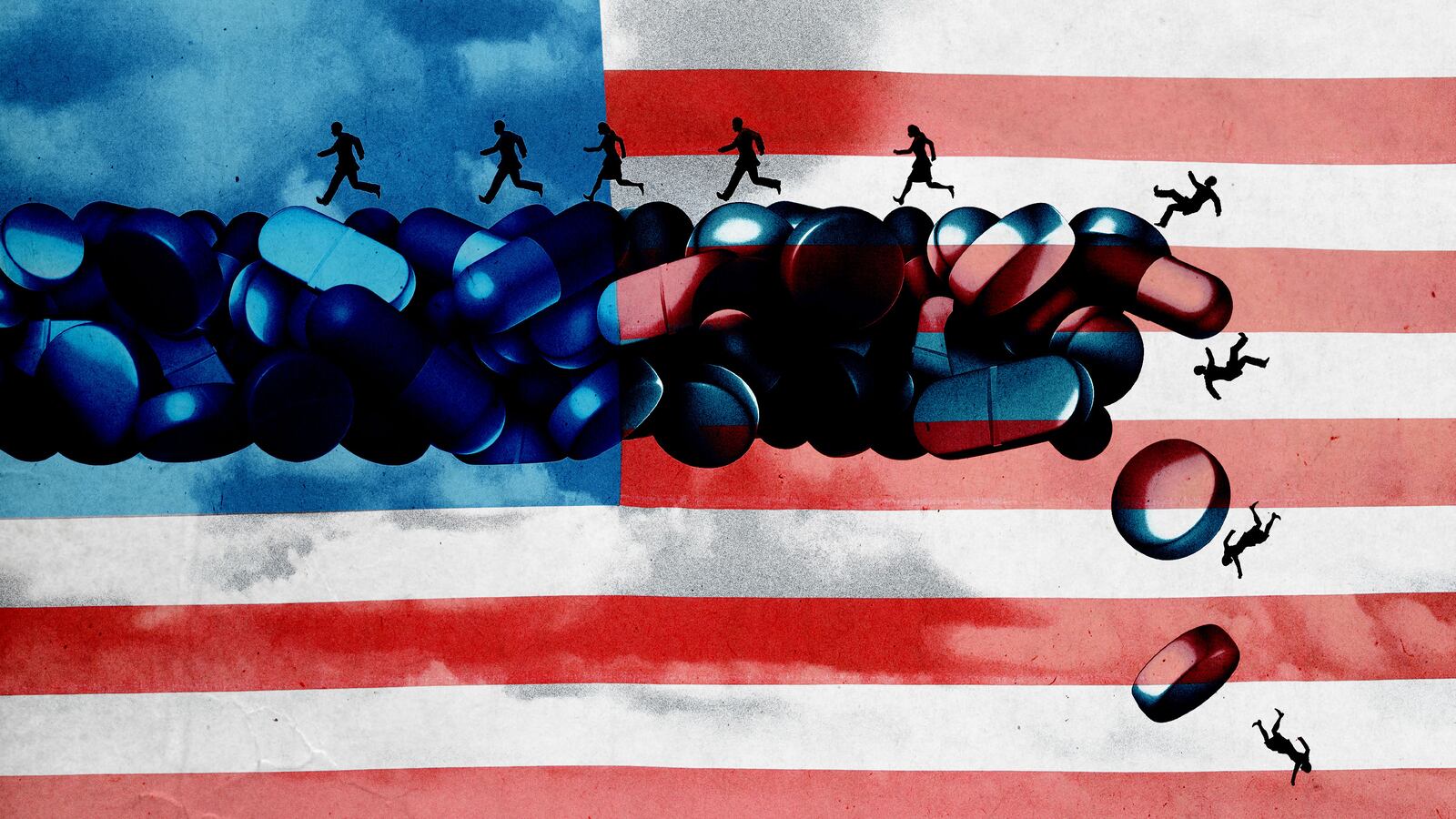

According to the CDC, opioids were involved in 68,630 overdose deaths in 2020, which made up about 75 percent of total drug overdose deaths that year. As these numbers continue to climb to all-time highs, better strategies grounded in data are necessary to provide relief—which won’t happen overnight..

In truth, there are a lot of different actions that could stem the rise in overdoses, but as COVID has shown, public health policy has to be choosy. Thankfully, a team of American scientists published a new study in Science Advances that strongly suggests there are three strategies in particular that may help save the most lives over the next 10 years.

The findings are thanks to a sophisticated model called Simulation of Opioid Use, Response, Consequences, and Effects (SOURCE), which can simulate patterns of the U.S. opioid-using population and make projections of how rates of opioid use and overdoses will change over time in response to different interventions.

“I wanted to see, using the model, what more could we do beyond what’s already being done to reduce overdoses?” Erin Stringfellow, a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, told The Daily Beast. “How do we actually get more people in treatment?”

SOURCE was first described in a paper that ran last month in the journal PNAS, which demonstrated the validity of the model and its ability to predict trends in opioid use based on different parameters. In their new paper published Friday, Stringfellow and her colleagues decided to go one step further and see what kind of actual recommendations they could glean by running simulation after simulation using SOURCE.

The model goes beyond simply assuming someone will just walk into a clinic and receive treatment, said Stringfellow. It takes into account the myriad of barriers to treatment—one of the biggest being that treatment facilities sometimes just don’t have the capacity or resources (e.g. drugs like naloxone, used to restore breathing during overdose) to help opioid users. The model also looks into the inefficiencies of distributing treatment to individuals in need.

Stringfellow and her team looked at 11 different approaches that could be used to prevent those with an opioid use disorder (OUD) from overdosing. SOURCE found three that stood out among the rest in reducing deaths through 2032: boosting fentanyl-focused harm reduction services; increasing naloxone distribution to people who use opioids; and boosting recovery support for people in remission, which reduced deaths by reducing OUD.

Fentanyl-focused harm reduction is particularly critical. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is more likely to cause overdose than heroin, has been implicated in over 67,000 fatal overdoses during 2021—a staggering 21 percent increase from the year prior. Stringfellow and her team point to the use of interventions like fentanyl tests as having a big potential in reducing the deaths. “It's not surprising that if you can do anything to reduce that risk that you're also going to save a lot of lives,” she said.

One additional finding that stood out was that increasing the capacity to provide buprenorphine (an alternative opioid used to help wean users off heroin) had short-term benefits in preventing overdose, but should not be seen as a long-term solution. Stringfellow thinks this is due in part to the fact that the prevalence of OUD is already declining, and should be declining anyway. “So there’s no reason to think we’re going to have a sudden increase in opioid use disorder in the coming years,” which means increasing the capacity to provide buprenorphine isn’t as essential, she said.

The model isn’t perfect, as the authors of the study are the first to point out. It’s looking strictly at opioid overdoses—specifically those who have OUD. It’s not looking at how to reduce opioid misuse in general, or at projections around overdoses that might involve another stimulant like methamphetamine or cocaine.

Nevertheless, the study is a valuable roadmap for what could be the best way to allocate limited resources toward a crisis that almost surely will not abate on its own. These are policies that may provide some relief to the many communities in the U.S. ravaged by opioid use.