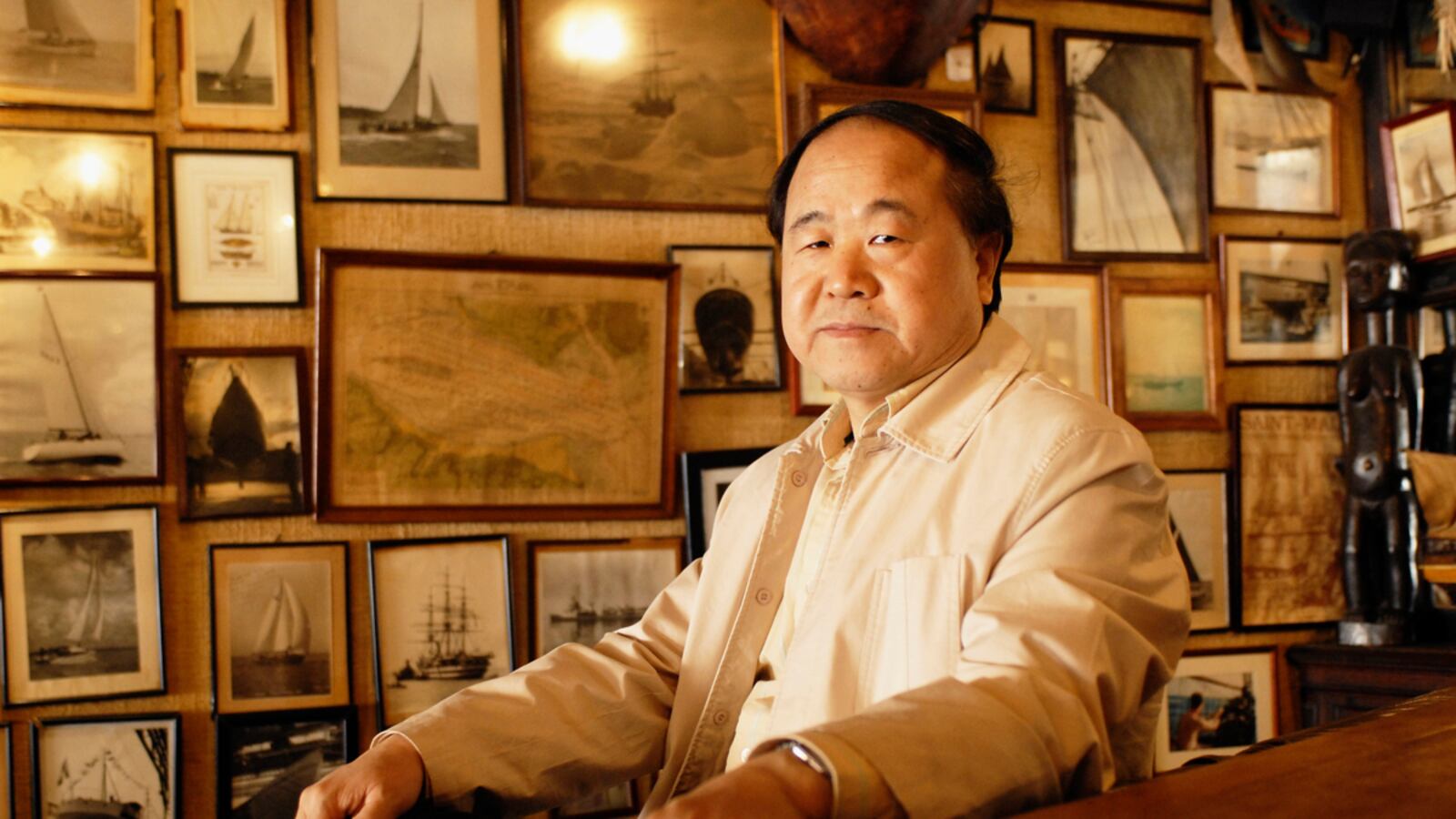

BiographyMo Yan was born to a family of farmers in the Gaomi township in Shandong province in northeastern China. During the Cultural Revolution, he had to leave school to work in an oil factory. At 20, he joined the People's Liberation Army and began writing while he was a soldier. In 1984 he was given a teaching position at the Department of Literature in the Army's Cultural Academy. (A "Mo Yan 101" by James Williford of Humanities.)

Pen NameMo Yan is not his real name. He was born Guan Moye. "Mo Yan" means "don't speak" in Chinese. While speaking at the Open University of Hong Kong, Mo said he chose the name because he was known for being outspoken, which isn't a good trait in communist China. The name was to remind himself not to talk too much. (Simon Elegant, in Time, writes on how Mo adroitly negotiates the edges of censorship.)

'Red Sorghum'His breakthrough came with the 1987 novel Red Sorghum. Set in a small village, it details peasant struggles during the anti-Japanese war. The film director Zhang Yimou turned the book into his first film, and it won the top prize at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1988, boosting Mo's popularity. Zhang would also adapt Mo's Shifu: You'll Do Anything for a Laugh into his 2000 film Happy Times. (Here's Yale professor Jonathan Spence's review of another of his works, Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out.)

Chinese Magical RealismMo writes in an exuberant, energetic, and highly metaphorical style about many visceral pleasures. His characters are often loquacious and satirical, capable of raunchy humor. John Updike, in The New Yorker, said of Mo, "Such surplus energy of figuration attests to, if not greatness, a greatly ambitious reach." In recent years, he has developed a style described as "Chinese magical realism." "Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives, Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent in its complexity of those in the writings of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition," the Nobel citation noted.

‘First Chinese Winner’Mo is the first official Chinese winner of the literature prize, though he is not the first Chinese writer to win. Gao Xingjian, artist and author of the novel Soul Mountain, won in 2000, but he had emigrated to France by that time, after years of criticizing China's government. The government disowned the prize when Gao won, as they did in 2011 when jailed dissident activist and literary critic Liu Xiaobo won the Peace Prize. Mo has lately been embraced by the government, and the award has been warmly welcomed by the Chinese authorities, with television broadcast breaking in to to announce the win. (Here's the official Xinhua agency report on the news.)