Deep into a moonless night after 9/11, Dr. Mike Brown headed into Central Park with 20 off-duty New York City firefighters he dubbed ”ninja gardeners.”

They soon came to a spot at the top of the Great Lawn corresponding to an X that his legendary brother, FDNY Capt. Patrick Brown, had marked on a map that he included in a letter to Mike to be opened in the event of his death.

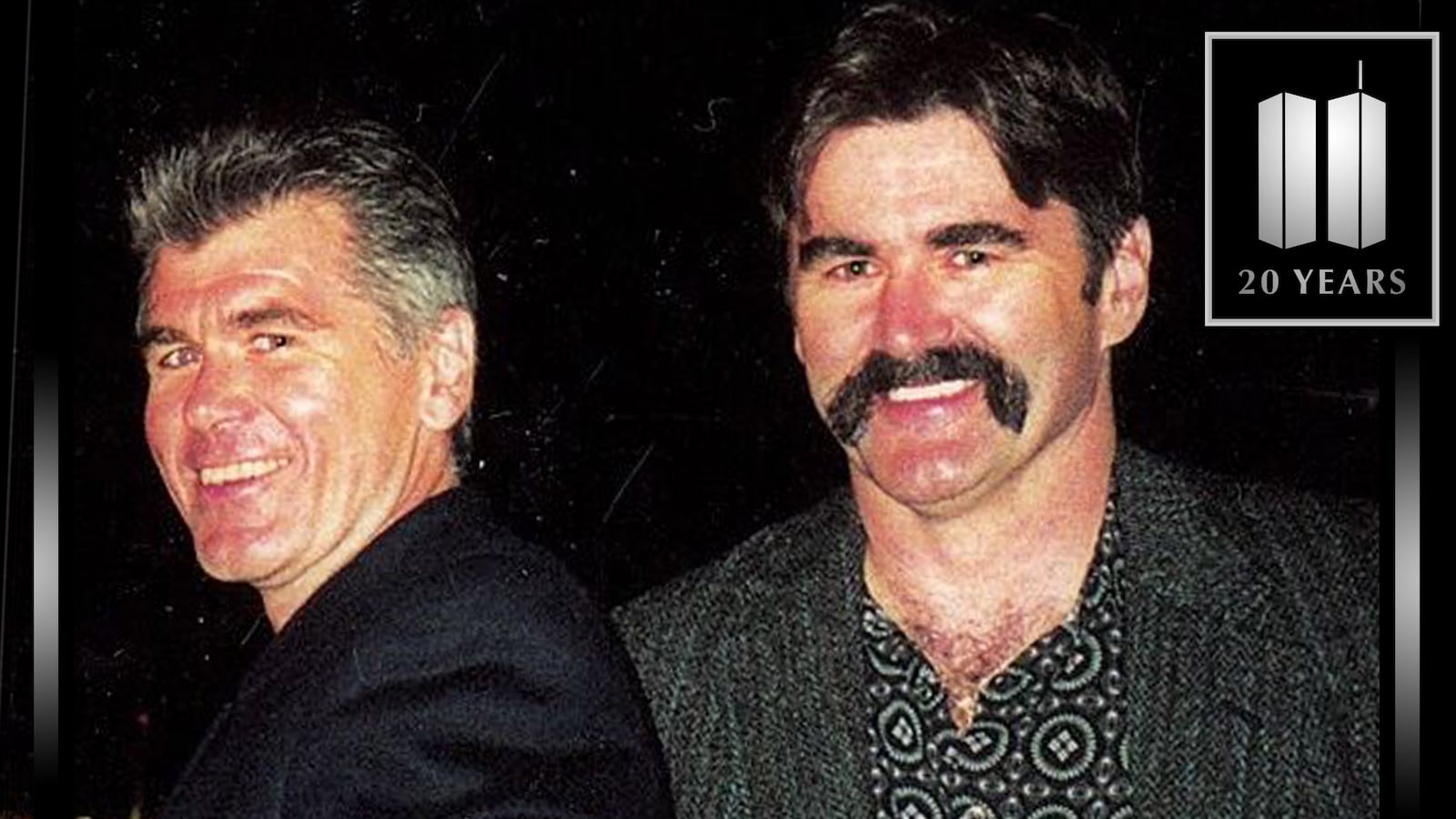

Mike had also been a firefighter, while attending medical school, and had become an emergency medicine doctor while Patrick—also known as Pat or Paddy to his friends—went on to become the most decorated member of the FDNY.

Mike was working a 6 a.m. shift in a Las Vegas emergency room when the wall-mounted TVs in each of the treatment rooms brought live coverage of an attack on the World Trade Center.

Images of people leaping from the burning towers played on a screen over his head as he tended to a 40-year-old woman who was giving birth to her first child. The infant was too premature to survive and the heart fluttered briefly and then stopped. Mike moved on to a teenage gunshot victim and then a man having a heart attack. He then had to inform a woman and her family that tests indicated she had metastatic pancreatic cancer.

“Dr. Brown, the tower fell!” a nursing assistant then called out.

Mike looked up at a TV and watched the billowing clouds clear. He saw that the south tower, the second to be hit, had been the first to fall. The north tower was still standing and Mike guessed the FDNY might have given an evacuation order.

“Run, Pat, run!” he told himself. “Run Pat, run.”

Then the north tower came down.

Mike called Pat’s firehouse, Ladder 3 on West 13th Street in Manhattan. He was told that Pat and 11 other members of the company were missing.

All flights were grounded and both the trains and the buses were sold out. Mike started driving and he kept driving for 2,500 miles. He learned after his arrival that there was a recording of Pat reporting from inside the north tower.

“There’s numerous civilians at all stairwells, numerous burn injuries are coming down. I’m trying to send them down first. Apparently, it’s above the 75th floor. I don’t know if they got there yet. OK, 3 Truck and we are still heading up. OK? Thank you.”

Pat had also been recorded responding to an explicit order for Ladder 3 to evacuate the building.

“This is the officer of Ladder Company 3: I refuse the order. I have too many burned people here with me, and I’m not leaving them.”

The letter for Mike was in Pat’s locker at Ladder 3.

“Cremate me + dump the ashes in Central Park. I marked a possible spot on the map where to do it. I like it there principally because I jog there and there’s a beautiful view of the manhattan skyline which looks really cool at night.”

The map that Pat Brown left for his brother Mike, explaining where he wanted his ashes scattered.

Courtesy Ylfa EdelsteinThe surviving members of the company gave Mike a Ladder 3 work shirt and he went unchallenged as he joined the search for Pat and the other missing firefighters at Ground Zero. When Pat’s remains had still not been found nearly two months later, Mike and his sister Carolyn went ahead and held a memorial at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Nov. 9—Pat’s 49th birthday.

In the absence of ashes to scatter on the spot Pat had marked, Mike decided to plant a tree. A Brown cousin bought a 21-foot sugar maple and stood by with it in the back of a truck on the night of Nov. 12 as Mike as the ninja gardeners set to digging with picks and shovels in their Ladder 3 work shirts.

They brought enough water to mix a cement base for a plaque, but realized they needed more for the tree itself. They called nearby Engine 74 for help with what they had imagined was a secret mission.

“They said, ‘Oh, you’re there with the tree?’” Mike later reported. “It turned out the whole department knew about it.”

NYPD radio cars rolled past twice. There were two nearly identical exchanges.

Cops: “What are you doing?”

Ninjas: “Planting a tree.”

Cops: “We didn’t see nothin’.”

Just after the tree was planted and the plaque was placed, actual trouble threatened with the arrival of the park’s night supervisor.

“What the hell are you doing?” he inquired.

The ninjas luckily included a cop, off-duty NYPD Detective Keith McLaughlin, whose firefighter brother, Peter, of Rescue 4 had died in an arson blaze on Oct. 8, 1995. Peter had been very close to Pat.

Keith now stepped up to save the night. He shook the supervisor’s hand and of course gave a false name.

“Hello, I’m Jim McFabbin, I think we may have spoken several times on the phone. We really appreciate your input on picking the right tree. Remember? You gave us two choices and we picked this one. What do you think? Look good?”

The night supervisor did not seem to know what to say or do.

“Oh yeah, yeah, it’s so beautiful,” he said. “It looks good there.”

“With all of us going to funerals and being down at Ground Zero digging, this is the only time we could do it,” Keith said. “Come on over, why don’t you meet everybody?”

Keith introduced the man to Mike. The man read the plaque:

“CAPTAIN PATRICK J. BROWN

WHO DEDICATED HIMSELF TO SAVING THE LIVES OF THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK. AND LOST HIS LIFE THAT DAY ALONG WITH SO MANY OF THE OTHER TRUE HEROES OF THE WORLD.

NOVEMBER 9, 1952- SEPTEMBER 11, 2001”

Keith told the night supervisor that thanks to him, everything would be ready in time for a big dedication ceremony.

“Uh, yeah, I remember seeing the memos on this,” the man said.

One of the ninjas gave a cry.

“God bless Paddy Brown!”

The night manager was inspired to thank the firefighters for all they had done for the city.

“I would also like to say God Bless Paddy Brown!” he added.

The night supervisor departed. The ninjas collected their picks and shovels and left the park soon after, giddy with the feeling they had actually gotten away with what they had come to do.

But, being a bunch of firemen, they had managed to plant a sugar maple in the Arthur Ross Pinetum, one of the world’s most famous collections of evergreens. The higher-ups ordered the tree and plaque removed.

In one of the many acts of unexpected nobility inspired by 9/11, some of the groundskeepers took it upon themselves to replant the maple amidst some deciduous trees nearby. They dug a perfectly circular hole ringed by fencing to protect the tree until it had taken root.

Pat and Mike Brown’s tree in Central Park.

Courtesy Ylfa EdelsteinMike’s wife, Janet, a nurse, had flown in and they boarded a plane back to Las Vegas. They were in mid-flight when a passenger collapsed and sprawled unconscious in the aisle. Mike attended to the man and determined that he might “code” and die if he did not get to a hospital quickly. An ambulance was waiting when the plane made an unscheduled landing in Columbus, Ohio.

The flight to Las Vegas continued on, and two hours later, one of the crew informed Mike that a woman was unconscious in the bathroom. She was not breathing and he had no detectable pulse.

“What we call clinically dead,” Mike later said.

A portable computerized defibrillator aboard the plane indicated that an electric shock would be of no help. The only hope was the epinephrine in the medical kit. Mike administered it and was thrilled to see the woman’s chest rise as her heart started pounding.

But, after a few minutes the epinephrine wore off, and the woman went into cardiac arrest again. Mike and Janet and three nurses who were traveling with them kept fighting to keep the woman alive. Somebody produced a second medical kit.

The epinephrine repeated its magic only to burn out just as quickly. The woman’s heart stopped again as the plane approached Las Vegas.

“She was as dead as she was when we found her,” Mike later said.

Mike called for the paramedics on the ground to be ready with a syringe of epinephrine. He kept working and said he felt as if he had been joined by the spirit of his fallen brother.

As the plane touched down, a flight attendant thanked Mike and the nurses over the P.A. system. The attendant had learned enough about them to add a final acknowledgment.

“And, God bless Paddy Brown!”

The paramedics rushed aboard with the epinephrine and the woman's heart was beating again as Mike inserted a breathing tube. He rode with her in an ambulance to the hospital, where her condition stabilized. He remembered Pat’s advice when he was torn between remaining a firefighter with Engine Co. 37 and becoming a doctor.

“I loved being a fireman,” Mike recalled. “He said, ‘Do what you want, but not too many people get a chance to be a doctor.’”

The recovery effort at Ground Zero continued into December, and Firefighter Bill Ells discovered some battered remains wearing firefighter boots with Brown and E69 written inside. Pat had worked at Engine 69 and everybody was sure it was him even before DNA confirmed it.

Pat Brown’s Ladder 3 helmet, as seen in the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

Roberto Machado Noa/GettyMike flew back to New York with Janet.

Late on the bitterly cold night of Dec. 30, Mike arrived with a white cardboard container labeled CAPTAIN PATRICK J. BROWN at the spot at the top of the Great Lawn that Pat had marked on the map. He opened it and went down a line of 30 mourners. Each took a modest handful of the ashes.

“Anybody need some more?” Mike then asked.

Mike went back down the line and each took a little more from the cardboard container. The gray ash was gritty to the touch. It rested in the palm as if disbelief had taken substance.

The remaining spires of Manhattan stood beyond the dark trees with incandescent majesty. The view was as cool at night as Pat had said in his letter.

On Mike’s instructions, the mourners turned toward the moon, which had been shining big and bright behind them in a city sky so clear you could actually see the stars. Everyone joined him in casting their handfuls into the icy air and calling out in one voice.

“God bless Paddy Brown!”

The breeze caught the ash and it stayed aloft, swirling and sparkling in the moonlight, as if the firefighter said to always be first in and last out had become a kind of heavenly dust.

Everybody still had gritty ash on their palms and fingers. That included the pregnant widow of a firefighter who was one of Pat’s closest friends and had died with him in the North Tower. She rubbed her hands on her face.

“Now I’ll know he’s watching over me,” she said.

Nobody wanted to take the last of the ashes, and Mike walked over to the replanted tree. He carefully poured what was left around the base. A fire widow led everybody in singing “God Bless America” and just as she ended with “...my home sweet home,” an airliner like the planes that struck the twin towers flew overhead, almost as if in tribute.

“The hardest thing was to get that plane to fly over,” Mike joked.

Mike returned to saving lives as an ER doc in Las Vegas and wrote a book called What Brothers Do about his efforts to fulfill Pat’s final wishes. Mike was back in New York with Janet at each anniversary of 9/11, wearing Ladder 3 work shirts that had Pat’s report from the tower stenciled on the back: “This is 3 Truck and we’re still heading up.”

They were at the fifth anniversary when they watched a girl about 7 use the end of a rose to carefully inscribe a single word in the dust where the north tower once stood.

“DADDY”

The sky-tearing roaring that accompanied the collapse of the towers was again marked by two moments of silence. Mike and Janet and a cousin headed for the nearby Hudson River to perform a more private ritual with three coins that had been recovered from the 1.8 million tons of debris removed from Ground Zero. The quarter and two dimes had been determined to have traces of Pat’s DNA. He must have had them in his pocket as he kept heading up to save daddies and mommies and sons and daughters. The coins had been mailed to Mike and Janet and she now had them in a velveteen pouch.

Back in 1995, Pat had come to the river’s edge with the wife of fellow FDNY Captain John Drennan, who was 14 days into a desperate fight to stay alive after suffering agonizing burns in a lower Manhattan fire. Pat had stood with Vina Drennan in the shadow of the World Trade Center and wished for her husband’s recovery as he tossed in a coin. That had not seemed enough and Pat tossed in a whole pocketful of change.

The captain died 26 days later, with Pat whispering in his ear, “You can go, John, you can go. We’ll take care of your family.”

Now, Patrick Brown was gone and Mike stood at the same spot as the coin toss. The quarter was a 1994, the two dimes a 1997 and a 1993. They were blackened at the edges. The 1997 dime had a small black smudge between the “L” and the “B” in LIBERTY.

The Statue of Liberty had her torch upraised in the distance as Janet gave the quarter to the cousin, a California fire captain named Jay Presten. She gave one of the dimes to Mike.

The coins arced into the sunlight. They hit the churning water, making three distinct little splashes and then they were gone.

“God Bless Paddy Brown!” they cried.

Janet had been fighting breast cancer since the year of the attack and became too ill to attend the 15th anniversary. She died 18 days later. There was a gathering at what had become known as Pat’s tree. It became Pat and Janet’s tree when her ashes were scattered at the base.

“God Bless Janet Brown!” the mourners cried.

By May of 2019, Mike himself was sick with an unusually aggressive type of prostate cancer seen in those who worked the Ground Zero recovery effort. His illness was officially classified as 9/11-related.

On May 9 of the following year, he was in New York to consult with an oncologist. He afterwards went by the tree with Ylfa Edelstein, who was Pat’s fiancee and had not let death change that. She took a picture of Mike hugging the tree.

Mike Brown embraces his brother’s tree.

Courtesy Ylfa EdelsteinCOVID-19 could not have stopped Mike from returning to attend the 19th anniversary of the attacks, but cancer did. He died in his Las Vegas home on Oct. 30, 2020. He was one of more than 3,400 said by the World Trade Center Health Program to have lost their lives to 9/11-related illnesses.

On March 20 of this year, those who loved Mike and Janet and Pat gathered at the tree again. Presten held a white cardboard box labeled BROWN, MICHAEL. Everyone took a handful of the ashes, which felt as unreal as Janet and Pat’s.

In unison, they tossed the latest ashes inside a big ring of red and white rose petals that Edelstein had placed around the base of the tree. One more noble spirit was taking up permanent residence.

“God Bless Mike Brown!” they cried.