In a few months, it will be 12 years since the U.S. war in Afghanistan began. The date will be marked on White House calendars, with policymakers in the Obama administration talking about 2014 as the “end” of the war. For Americans, this will be another American war wound down but not won. For Afghans, however, there will still be a NATO presence, and they will face strife that for them has dragged on across more than three decades.

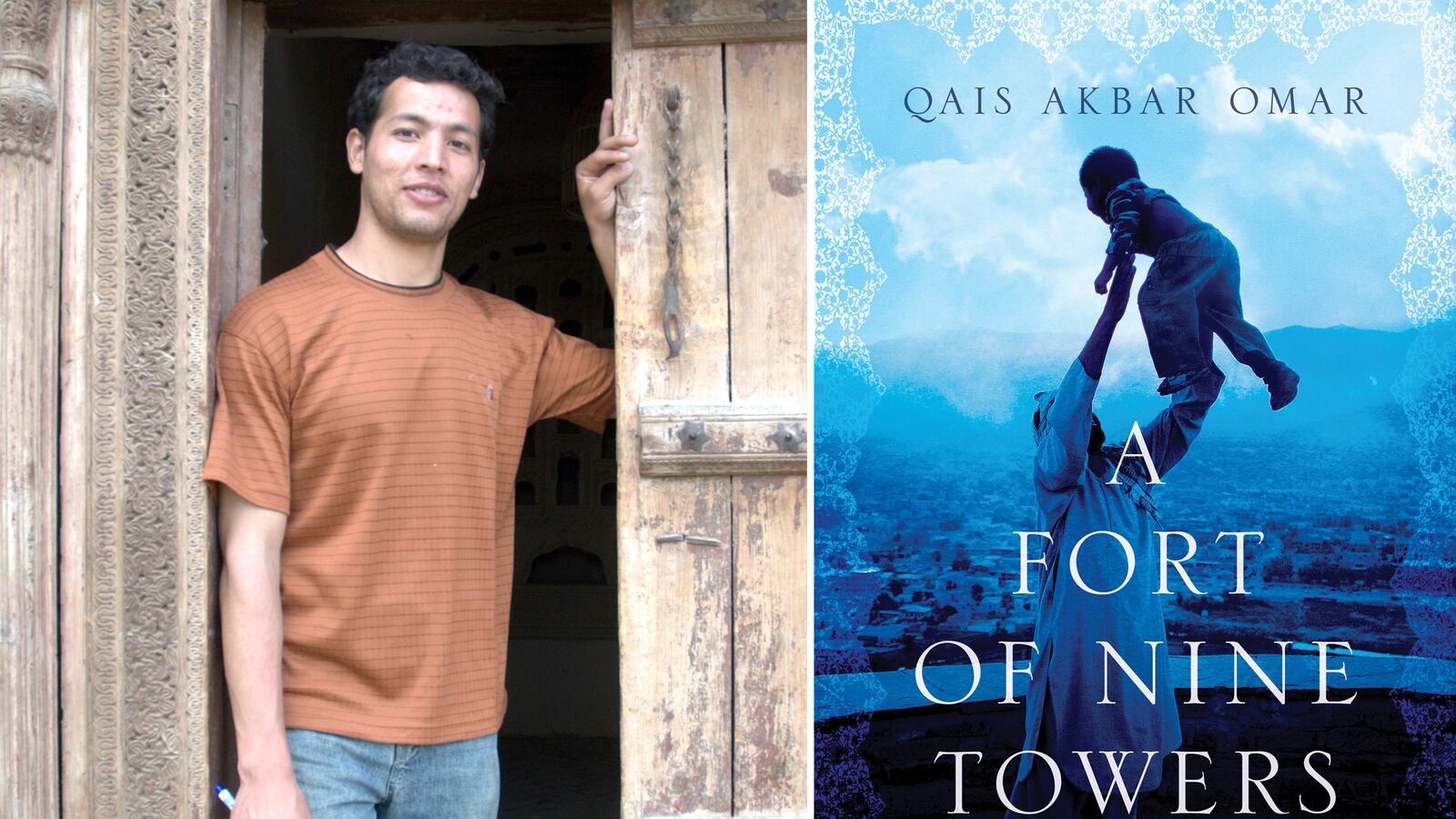

Qais Akbar Omar, a student in the Master of Fine Arts creative-writing program at Boston University, is also a native Afghan carpet weaver. “I know how, slowly, one knot follows another until a pattern appears,” he writes in his extraordinary new memoir, A Fort of Nine Towers. It stands apart from other books on Afghanistan—shelf space that’s becoming crowded again, and, thankfully, with writing from Afghan perspectives. Reporters, troops, and academics have chronicled the country, but often from a distance—strangers in a strange land. These contributions helped pull back the curtain on diplomatic history, war policy, and the initial naivety and ongoing challenges of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism strategy. Other authors have crafted frontline fiction based on their tours in the post-9/11 wars.

But Qais’s spirited voice is distinct. While not a critique of the current U.S.-led NATO effort, his quiet book calls the American bluff in other ways. His family has survived all his country’s troubled transitions, from the Soviet occupation, the mujahedin warlords, and the Taliban to the war today. “Even the Taliban’s strangest laws were easier to survive than the chaos of the commanders,” he writes. It serves to remind readers that while Afghans can make “no better friend,” they also have a tradition of being “no worse enemy,” especially toward foreigners. This is worth keeping in mind as policymakers in Washington seek to end the longest war in American history. The story of Qais’s family is the story of Afghanistan.

Qais is an Afghan of mixed ethnic heritage, self-described as “a Pashtun with Hazara eyes.” Afghans, he reminds us, once “lived well” before their spiral into violence. In the 1950s, life in Afghanistan included public debate, educated and working women without burqas or veils, and economic progress. Headlines today highlighting assassinations, roadside bombs, and school burnings make this past setting hard to imagine. Qais manages to do just that by prefacing his family’s early privileged life in Kabul. But war soon ravaged the terrain. Sniper bullets, mortars, and rockets land in Qais’s neighborhood with lasting consequences. His family had to flee, and he goes on a geographic as well as an inward journey as the young Qais matures fast.

Qais compels readers to see his country unfiltered, as it once was and now is, and not through a foreign lens. He shows how mine-riddled Afghanistan remains filled with natural beauty. The scent of naan bread fills your nose, colorful fruit trees bloom between mud walls, and bracing winds sweep down through the valley between mountain peaks. He piques all your senses, but the details are further juxtaposed with raw descriptions of suffering and death. I spent almost three years in Afghanistan with the State Department and have waited a long time for a nonfiction account like Qais’s, one that captures the resilience of the people amid the jagged landscape of the Hindu Kush.

Qais’s family embarked on an odyssey through multiple regions of the country, including Bamiyan (where they lived in the caves next to the now destroyed Buddha statues), Kunduz, and Mazar-e Sharif, listening to BBC World Service updates on the radio whenever they could. For a time they join the nomadic Kuchi tribes. The Kuchi are wandering people who carry animal-skin tents across hundreds of miles every year. Their faces are wrinkled by the sun as they look to the sky for signs to pack up and avoid the snow, always attempting to be a few steps ahead of winter. But no one offers more hospitality despite having so little. And they fish with hand grenades, a strategy as efficient as it is memorable. Qais’s succinct travelogue prose paints lasting pictures, and he is particularly good at describing the arrival of the Taliban in 1996. They reminded him of vampires:

All of them had outlined their eyes in kohl. Their beards were untrimmed and long. None had proper shoes. Instead they wore slippers, and their feet were dusty. Most of them had snuff in their mouths. A few of them spat brown saliva into the dust in front of them and then cleaned their mouths with the ends of their turbans. None of them spoke. They looked lost, like men who had come from a forest or caves and had never seen buildings before. I thought at first they might be vampires. I knew that vampires did not exist, except in stories to scare kids. But what else could I be seeing?

During his family’s long trek, he meets a deaf and mute Turkmen girl and learns carpet weaving from her. When the family at last returns to Kabul during the reign of the Taliban, Qais establishes a factory with its own weavers and runs the family business. The Americans invaded in 2001, and with thousands dead and billions spent in Afghanistan thus far, A Fort of Nine Towers concludes with a wry commentary as Qais describes coalition members bartering for his rugs. The French are picky; they never pay a fair price, but they have the best food. The Italians are loud, like the Afghans. They pay the full price, but leave in a hurry, because they are always late. The British are imperial in their ways, because they are unable to escape their past. And the Americans? They are friendly, they always pay the full price, and they want to know everything. But even though they are the most agreeable of the new visitors, Qais’s father views them with considerable skepticism:

Afghans have fought each other for millennia. We have a long tradition of raiding and plundering each other. But two things unite us: love for Allah and hatred for our invaders and enemies. We are not leaving Afghanistan until we find out if these Americans are our real friends or enemies in the mask of friends.

It’s now been over a decade, and Afghans remain unsure about American intentions and endurance. Qais’s narrative cuts through hardened pro- or anti-war biases to record both the pain and pride that remain the hallmark of so many Afghans. They’re used to it, because, in Qais’s words, “war never stopped chasing us.”