One hundred years to the day after women first won the right to vote in America, and the country is in a weird, dark place.

There’s a kind of brutal symmetry between 1920, when the mass exodus of women from the home and into the workforce supercharged the movement, and 2020, as the pandemic forces working women back into the home.

It’s all so retro. Even Kamala Harris, the first Black and South Asian woman on a major party’s presidential ticket, has to weather viciously misogynistic attacks while also pandering to 19th century notions of womanhood. Harris—who was 49 years old and the attorney general of California when she got married—recently described the title her step-kids gave her, “Momala,” as “the one that means the most.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Much the same way that Michelle Obama transformed herself from a Harvard-educated lawyer into "Mom in Chief,” or Hilary Clinton in 2015 and 2016 kept stressing her roles as a grandmother and a mother while running to be commander-in-chief, women still have to minimize or explain themselves in the context of family. Meanwhile, it’s practically unheard of for a man, political candidate or otherwise, to qualify his work with a statement about fatherhood.

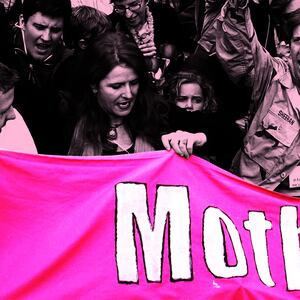

This ongoing pablum about motherhood is part of the same hoax that once denied women the right to vote. If being a mom is the most important job, then the government doesn’t need to guarantee women equal pay, paid leave, subsidized childcare, or even the franchise.

The suffragists knew this, and in 1907, they rebranded with the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, to draw in women from the industrial trades. Sick of being condescended to as the weaker sex, and inspired by the British suffragists who made headlines for heckling political candidates and getting beaten up by police, the Americans muscled up a previously chaste cause. Instead of temperance and moral purity, they talked about money. As the US Labor Commissioner, Carroll Wright (a man), put it in 1910: “the lack of direct political influence constitutes a powerful reason why women’s wages have been kept at a minimum.”

The same could be said in 2020. While women’s participation in politics has skyrocketed, and the franchise was eventually, belatedly extended to women of all races, gender representation is nowhere near parity. The Democratic presidential contest started with six female candidates and ended with a white man choosing one of them to fill out his ticket. That secondary position is reflected in the workforce, too, where it’s been compounded by the coronavirus and the Trump administration’s failed response to it. A study conducted in March and April found that telecommuting mothers were doing five times more childcare than their husbands, and less paid work as a result, thus expanding the existing gender gap in work hours by 20 to 50 percent. Another study found a precipitous drop-off in publishing among female academics in May. It’s Arlie Hochschild’s “Second Shift” on steroids.

That downward spiral is threatening to squeeze women out of the workforce altogether. Senator Elizabeth Warren, the last woman to exit the presidential campaign and the only candidate with a full plan for universal childcare, has linked the caregiving crisis to economic recovery. Predictably, there haven’t been so many men rallying to her cause.

Yet the influx of women into the workforce, and subsequent rise of the Labor movement, was a key turning point in the “century of struggle” that culminated in the 19th Amendment, as documented by Eleanor Flexner’s definitive history of the same title. That decades-long process moved women away from a purely domestic identity bound up in their biology, and helped deprive their opponents of a central argument; as wards of their husbands and fathers, women (“privileged” and “white” were implied) did not need — nor could they handle —direct political representation in public life. The hypocrisy, as well as the racist double standard, was obvious to Margaret Fuller, the first woman on the staff of the New York Tribune, even in 1845: “Those who think the physical circumstance of Woman would make a part in the affairs of national governance unsuitable are by no means those who think it impossible for the Negresses to endure field work even during pregnancy or for seamstresses to go through their killing labors.”

Generations of women subsequently centered work outside the home to justify their fight for equality. Betty Friedan’s 1963 classic The Feminine Mystique kicked off second-wave feminism by identifying “the problem that has no name” as the lack of professional opportunities for overeducated and under-stimulated housewives. And the National Women’s Political Caucus was specifically founded in response to the failed 1970 Equal Rights Amendment, to get more women elected to public office and party positions. But the gains of the following decades of activism, which culminated in the 2018 election cycle with more women running for office and voting than ever before, are about to be tested.

All of which is to say this: We better hope that women, whether they are homebound or risking their lives at work to support their families, can fill out their ballots this year.