Ahmed Salem bin Ali Jaber, better known as Salem, was an imam who preached against al Qaeda in Yemen. Waleed bin Ali Jaber, Salem’s son, was a traffic cop. On Aug. 29, 2012, a U.S. drone strike killed them. On Monday, the American justice system buried them.

Faisal bin Ali Jaber is Salem’s brother-in-law—he preferred to say brother—and Waleed’s uncle. Two years after the strike, Faisal received a plastic bag from a Yemeni intelligence official. Inside was $100,000 in sequential bills—not Yemeni rials, American dollars. It was twice the $25,000 per dead innocent relative that has become a grim, underreported ritual of the U.S. drone war in Yemen. But it was more than blood money, Faisal believed. It was hush money.

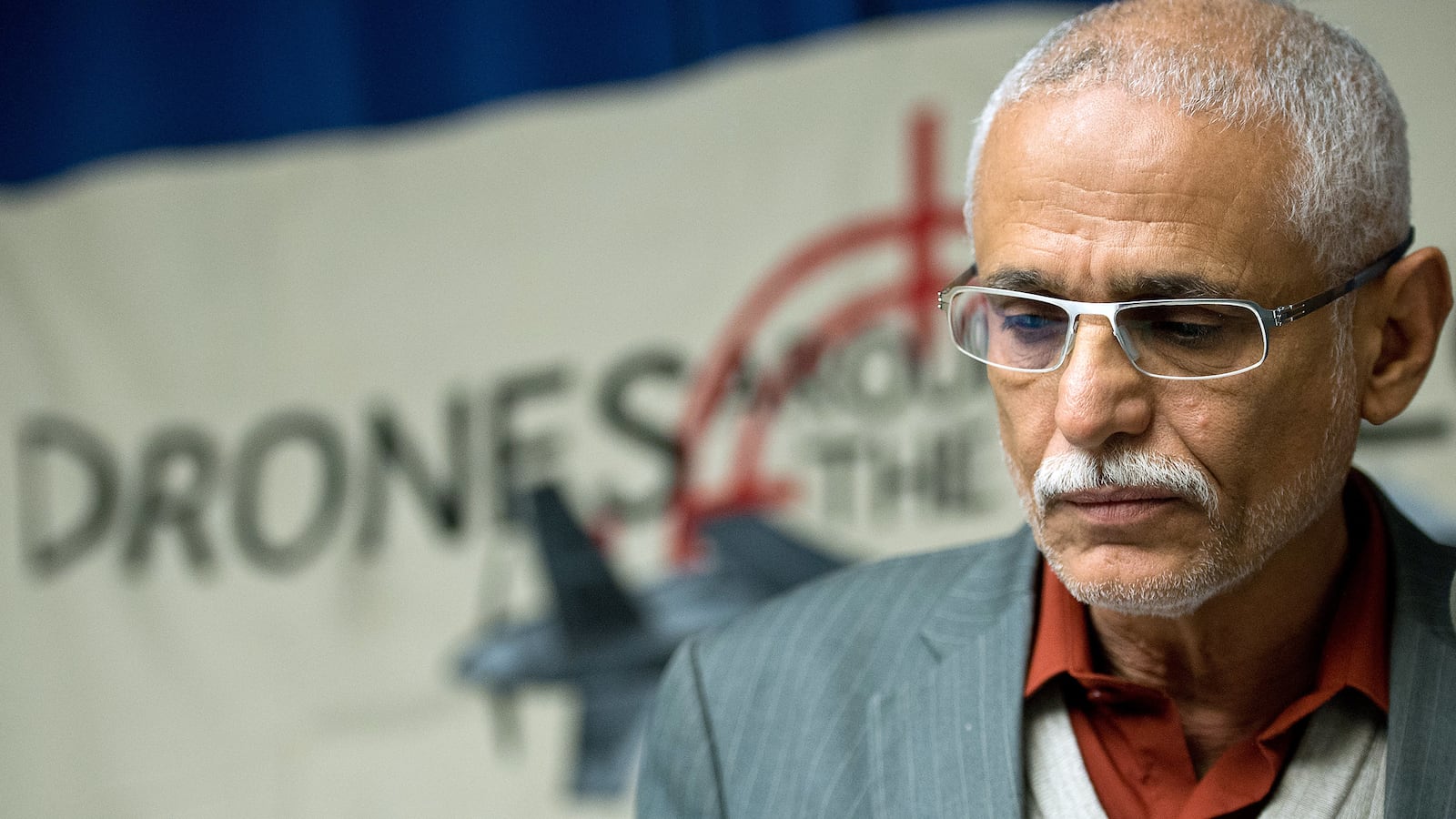

Faisal, a 59-year-old environmental engineer, told me last year that he had put the money in escrow, pending the conclusion of a crusade he has waged since his brother and nephew died. He wants one thing from Washington: a public apology. Faisal wants basic recognition of something all of us know from our daily lives—we make mistakes, even awful ones, and as the severity of our mistakes intensify, so too does our obligation to make restitution.

Faisal will never get what he wants for Salem and Waleed. On Monday, the Supreme Court released a list of cases that, among other things, it won’t hear. Among them is Jaber, Ahmed S. et al v. United States et al. (PDF).

Barack Obama’s White House launched and then institutionalized an apparatus of what it called “targeted killing,” implemented through armed drones. Whatever targeting occurred was insufficient to distinguish terrorists from a preacher who denounced them, along with a policeman who made the mistake of riding in a car with his dad. During the Obama administration, the CIA and the military carried out 183 drone strikes that killed at least 1000 people; the New America Foundation assesses that between 89 and 101 of them were civilians.

Obama’s administration gestured at the idea of justice for Salem and Waleed without ever actually getting around to providing it. In November 2013, Faisal got an audience at the White House with National Security Council staffers. He told me at a nearby Starbucks that everyone he met was nice to him, and “on the personal level they maybe feel sorry and apologetic,” but ultimately nothing really came of the meeting. It seemed at the time like the White House, which quickly confirmed the meeting, was patting itself on the back for taking the time to hear him out.

Faisal persisted. He filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking restitution, though he had no illusion that he would receive it. By October 2015, with Obama at that point backing Saudi Arabia’s pitiless and indiscriminate war in Yemen, he told the Justice Department he was willing to drop the suit if he received, in the words of his lawyer, “an apology and an explanation as to why a strike that killed two innocent civilians was authorized.” The Justice Department declined.

It did not escape Faisal’s notice that Obama had apologized for the deaths of two Westerners, Warren Weinstein and Giovanni Lo Porto, held captive by terrorists and killed in a drone strike. To Faisal, the lack of an apology signaled that Yemenis like Salem and Waleed, trapped in the U.S.’ war on terrorism, count for less than white people.

That ugly dynamic is truer today. Obama’s “targeted killing” program was, in his telling, an ethical balance between the need to combat terrorism and the need to restrain counterterrorism from swallowing U.S. foreign policy. Donald Trump won the presidency in part by sneering at the very concept of striking a balance—bomb the shit out of them, take out their families—and has governed accordingly as president. The New York Times reported last month that Trump gave the Pentagon and CIA “broader latitude to pursue counterterrorism drone strikes and commando raids away from traditional battlefields.” On the traditional battlefields, air strikes are way up. As long as Saudi Arabia shares Trump’s hostility to Iran, it has his green light to intensify in Yemen one of the world’s most appalling humanitarian crises.

“With Trump overseeing a massive expansion of secret strikes,” emailed Katie Taylor, a deputy director of Reprieve, the human-rights group that helped Faisal’s lawsuit, “it’s deeply worrying that the courts feel unable to check his powers. Congress must now urgently overhaul the legislation that enables the drone program—otherwise there will be many more innocents killed.”

But betting on Congress to restrain the war on terrorism is a sure way to lose money. A federal judge who felt she had no legal choice but to rule against the Jaber family wrote in June: “congressional oversight is a joke—and a bad one at that. … Our democracy is broken. We must, however, hope that it is not incurably so. “

The deck was stacked against Faisal—just like it is against all the past, present, and future Salems and Waleeds of the so-called Forever War. The U.S. government will always have reasons it can cite for why it cannot publicly acknowledge its lethal mistakes: operational secrecy, foreign-policy necessity, the inevitability of civilian casualties in war. The courts will always be reluctant to second-guess war powers that the constitution vests in the president and congress and even moreso when it comes to specific battlefield judgments. Americans will always give their security agencies the benefit of the doubt over foreigners.

Salem, Waleed and Faisal did what the U.S. government claimed to want locals besieged by terrorism to do. They used their religious authority to assail al Qaeda. They took responsibility for lawfully providing their neighbors with security. They sought a redress of their grievances through legal channels. And they learned that when measured against the interests of the war on terrorism, their lives did not and do not matter.