Sonia Kennebeck begins her documentary Enemies of the State with an epigraph from Oscar Wilde: “The truth is never pure and rarely simple.” By the conclusion of Kennebeck’s film, which premiered this week at the Toronto International Film Festival, the convoluted series of events she recounts reveal that nothing is straightforward about the case her documentary dissects—the strange saga of Matt DeHart, a man hailed by his supporters as a whistleblower and denounced by his detractors as a sex predator. Instead of assuaging the audience’s curiosity and providing a clear-cut resolution to this murky scenario, Kennebeck, whether courageously or perversely, leaves her viewers hanging. Perhaps the opaque nature of the DeHart controversy, replete with unyielding positions from partisans on both sides, leaves her no choice.

The legal and ethical quandaries posed by DeHart’s case seemed tailor-made to polarize opposing political factions, even though the terms of the debate reflect a pre-Trump era when the FBI and CIA were still mistrusted by liberals and Julian Assange and WikiLeaks were not presumed to be linked to Russian disinformation schemes.

The frequently mind-boggling details of DeHart’s plight are intrinsically disorienting inasmuch as they easily inspire diametrically opposed interpretations. In 2009, DeHart, at the time an intelligence analyst for the Air National Guard, claimed to have discovered explosive evidence of a CIA plot to implement the anthrax attacks of 2001, ostensibly designed to draw the United States into a war with Iraq that was promoted years earlier by the Bush administration. A hacktivist allied with the group of online guerrillas known as “Anonymous” as well as WikiLeaks, DeHart became understandably paranoid and, in early 2010, his Indiana house was raided by law enforcement authorities and he soon takes flight, first unsuccessfully seeking asylum in both the Russian and Venezuelan embassies and then finding refuge in Quebec as he decides to prepare for life in Canada by studying French. Meanwhile, prosecutors in Tennessee claim that investigations have produced evidence that DeHart solicited child pornography from two victims. DeHart has always strenuously denied these accusations and claims they are being weaponized as subterfuge by U.S. intelligence to deflect from his efforts to expose the malfeasance of the American government during the post-9/11 era.

Kennebeck does her best to be scrupulously objective about the dizzying twists and turns of an inevitably confusing narrative and interviews both diehard DeHart sympathizers and a Tennessee prosecutor and policeman convinced of his guilt. Of course, the waters become even more muddied when DeHart attempts to renew his Canadian student visa in 2010 and is quickly arrested by U.S. authorities when he crosses the border. He maintains that he was then drugged and tortured by the FBI and suffered a near-psychotic episode as a result. This vertiginous series of events repeats itself subsequently when, in 2013, after pre-trial deliberations, DeHart, accompanied by his supportive parents, once again applies for asylum in Canada, and, after an unpleasant sojourn in prison, is championed by journalists—especially National Post’s Adrian Humphreys, as well as Courage, an organization that vigorously defends the free speech rights of whistleblowers such as Julian Assange and Edward Snowden. Yet when the Canadian authorities fail to find sufficient grounds for granting DeHart asylum in 2015, he is deported to the U.S. and eventually accepts a plea deal for the child pornography charges and is sentenced to a term of seven and a half years. Nevertheless, after his sentence was “recalculated,” he was released from prison in 2019.

Kennebeck, despite her best intentions, cannot help but fall down a certain rabbit hole in which the bewildering, uncertain nature of all of these accusations and counter-accusations cannot be resolved and the viewer is forced to conclude either that DeHart has been the victim of a nefarious smear campaign spearheaded by American intelligence, which benefits from Americans’ gullible assumptions concerning the supposedly ubiquitous presence of pedophilia in our midst (which has only increased with the recent burgeoning popularity of deranged conspiracy theories such as QAnon), or is attempting to camouflage his involvement with child porn by emphasizing the unsavory motivations of both the FBI and CIA.

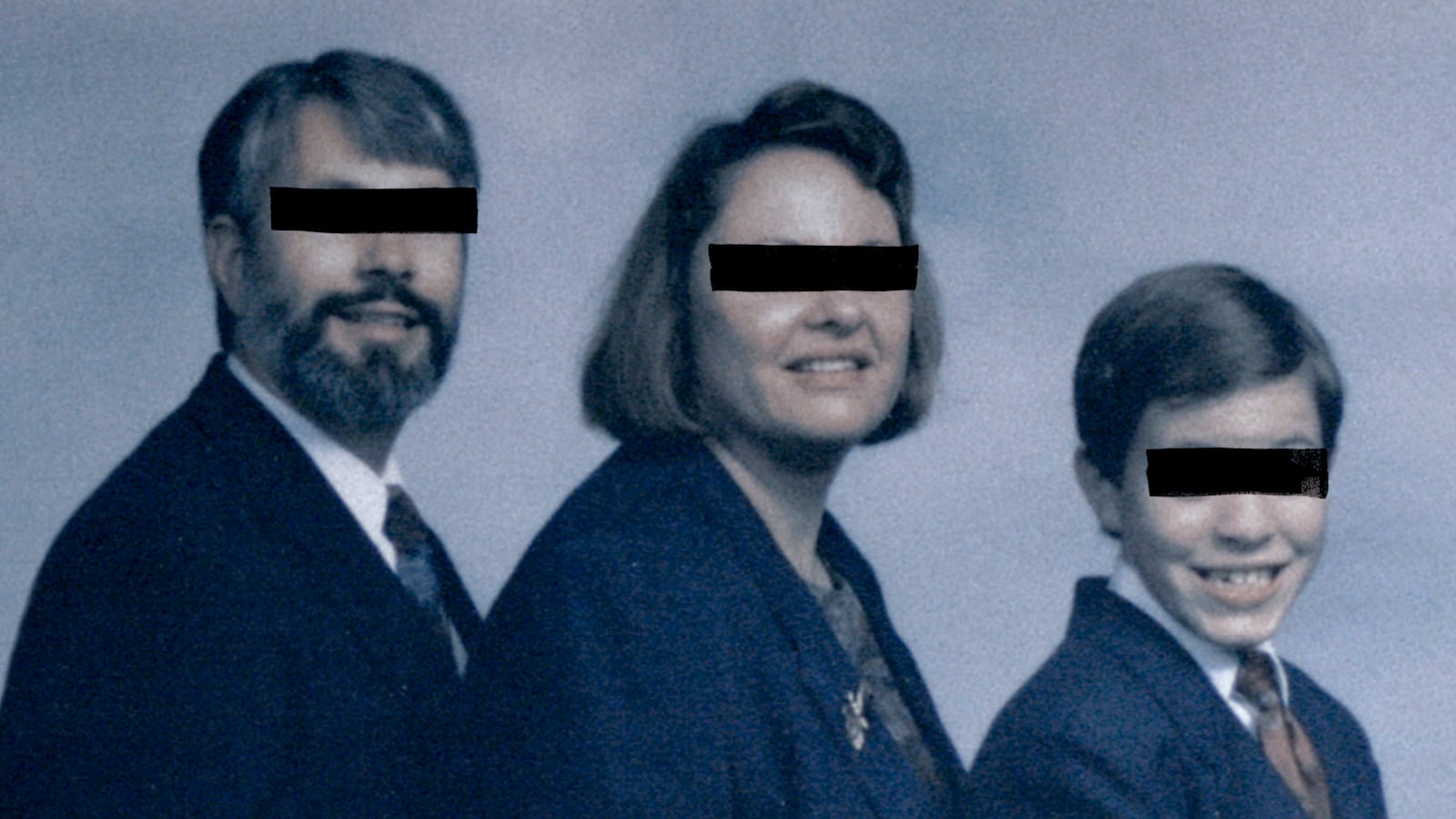

Even the established facts in this tangled web of conflicting narratives are undermined when the most steadfast DeHart defenders interviewed in the film appear to shift their positions when evidence of unsavory images unearthed by the Tennessee authorities (although how can one be sure this evidence isn’t tainted by government manipulation?) appear to confirm DeHart’s guilt. His parents, Paul and Leann, never waver in their insistence that their son has been framed. Other interviewees, particularly Humphreys and Gabriella Coleman, a professor at McGill University in Montreal and author of Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous, while refusing to condemn DeHart, seem more ambivalent about the young hacker’s previous status as an unblemished hero by the film’s end.

It’s certainly no coincidence that Errol Morris signed on as Enemies of the State’s executive producer. The film reflects many of the strongest and weakest attributes of Morris’s work. Morris’s best documentaries, especially his landmark investigative film The Thin Blue Line (1988) and Wormwood (2017), his more recent Netflix series, skillfully create an eerie ambiance by intermingling interviews, re-enactments, and an ominous musical soundtrack to enshrine heroic victims. Unfortunately, these stratagems, at their worst, become hollow gimmicks.

Perhaps through no fault of her own, Kennebeck’s efforts as a Morris epigone flounder because the facts prove unreliable, and DeHart remains as much of an enigma at the end of her documentary as he was at its beginning. It’s also arguable that her unwillingness to come down on one side or another of the DeHart imbroglio is something of a copout. Leaving conclusions up to the viewer can occasionally serve as a rationale for abdicating directorial responsibility. It’s also quite possible that Kennebeck finds it impossible to assess the contradictory evidence wrought by DeHart’s legal entanglements, and can only invite viewers into an ethical purgatory where uncertainty is inevitable.